©Copyright 2018 GEOSCIENCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE

11060 Campus Street • Loma Linda, California 92350 • 909-558-4548

THE UNITY OF THE CREATION ACCOUNT

by

William H. Shea

Associate Professor of Old Testament

Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan

Related pages | REACTION |

WHAT THIS ARTICLE IS ABOUT

Using the principles of biblical criticism, scholars since the past century have determined the first two chapters of the book of Genesis to be two different — even antithetical — accounts of creation, supposedly separated in source by several centuries. If indeed their assumption is correct, then the creation accounts do not necessarily represent a historically accurate record of God’s creative acts.

In this article, Dr. Shea examines the literary structure of Genesis 1 and 2. He concludes that the formulaic language and striking parallelism of subject matter in Genesis 1 are characteristic of poetry, although its meter is non-poetic. Genesis 2 resembles the structure of normal prose. The themes are unified, and the description of an event using the pattern of poetry/prose is common, not only in other portions of the Old Testament, but also in literature of Israel’s neighbors. Furthermore, the composition of these combinations of poetry/prose is considered to be essentially contemporaneous.

From the thematic unity between the two chapters in Genesis, from the many form features they share in common, and from the intricate and detailed nature of some of these formal relationships, the author concludes that Genesis 1 and 2, written by one author, are complementary halves of a unified account of God’s creative acts.

To further support his case for the single authorship, Dr. Shea turns his attention to the different names for the deity in the two chapters. Scholars have used the different names to prove separate authorships — centuries apart. After examining the names in both accounts, he finds that the names change only at the creation of man. He concludes that a “name” theology was involved in this distribution of names, because the author of the account wanted to say something about the personal involvement of the Creator God.

I. THE PROBLEM

With the rise of biblical criticism in the Age of Rationalism, the Scriptures underwent a penetrating re-analysis. One major aim of this new analysis was to determine and sort the literary sources from which the books of the Bible had been compiled. A parade example of this task comes from the first two chapters of Genesis where, it is claimed, are given two different even antithetical accounts of creation. Most critics separate the composition of these two sources by several centuries, attributing the Yahwist (J) account in Genesis 2 to the 10th century B.C. and the Priestly (P) account in Genesis 1 to the 6th century B.C. It follows, from this viewpoint, that if these two accounts were composed by different authors centuries apart, one need not be surprised to find discrepancies between them when they are compared. Thus a recent commentary on Genesis 2 describes supposed differences in approach and emphasis, then concludes:

This far-reaching divergence in basic philosophy would alone be sufficient to warn the reader that two separate sources appear to be involved, one heaven-centered and the other earth-centered.... In short, there are ample grounds for recognizing the hand of P in the preceding statement, as against that of J in the present narrative[1].

This conclusion about the first two chapters of Genesis can be investigated chiefly through examining their two main features: form (literary structure) and content (the distribution of the divine names).

II. LITERARY ANALYSIS

A. The Literary Structure of Genesis One

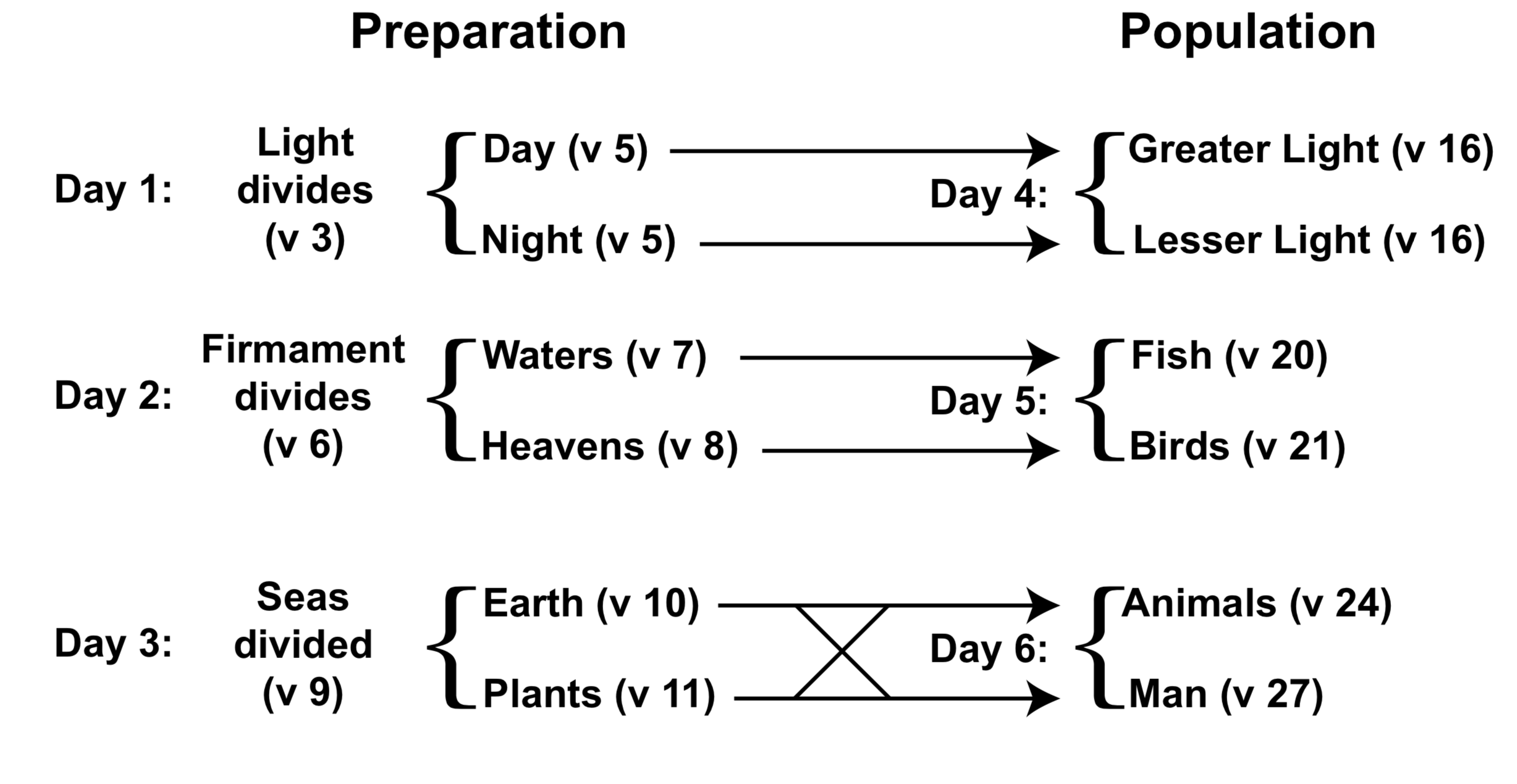

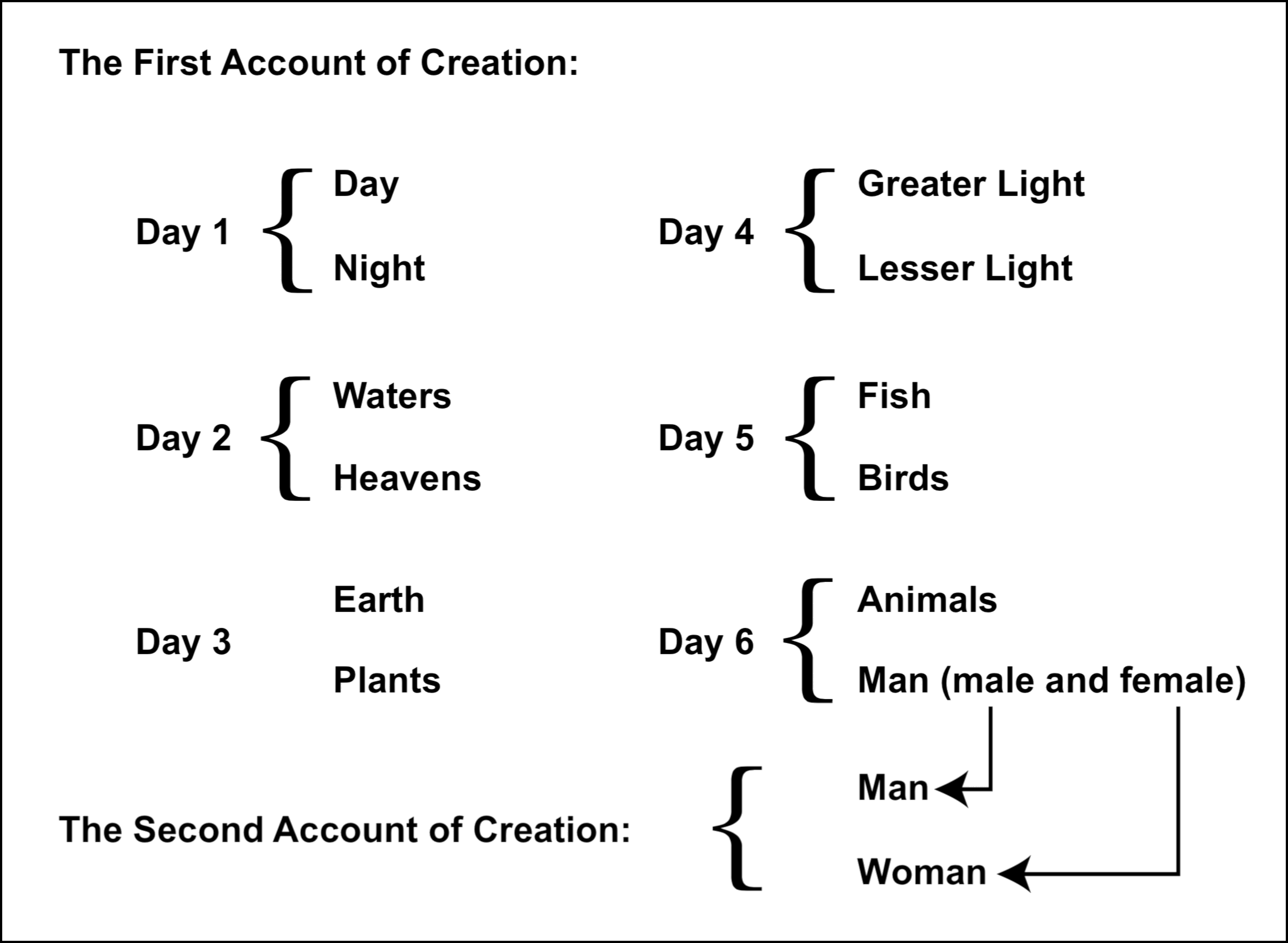

Commentators on Genesis have long noted a certain parallelism of subject matter within the account of creation contained in Genesis 1, i.e., between what occurred on the first three days of creation and what occurred on the second three days [2]. I concur with those interpreters who have emphasized the parallel nature of these creative acts and suggest that such parallelism may be even more far-reaching than has previously been noted. A schematic outline of this chapter demonstrates these relationships.

Not only is there a general parallelism between the first and last three days of creation, but also a parallelism within each creative day all the way through the creation week, for the activity of each day consisted of either two creative acts or one creative act which resulted in the division or identification of two essential elements in nature. The apparent exceptions to this duality of activity or objects on each creation day should be explained.

Only light was created on the first day, but that light divided off day and night, both of which were named by God at that time. On the second day the only new element identified specifically as made was the firmament, but it divided the waters above from the waters below; so the end result of this action was to arrange these two elements of nature in this way. The waters below were not named Seas until the third day when they were rearranged to make way for the emergent dry land (earth), but the really new elements that appeared on this day were the earth and plant life. Aside from the creation of land animals and man, the record of the sixth day includes the assignment of dominion over those animals to man and the designation of plant life, created on the third day, to serve as food for both man and beast.

On the whole, emphasis is placed upon two particular elements on each day of creation, and these two elements on the first three days relate to the two elements evident on each of the last three days. Thus the account contains elements of parallelism on the larger scale (between the first and last three days of creation) and on the smaller scale (with two elements per day). This smaller scale of parallelism in the creative acts of God is of some importance when this account of creation is compared with that which appears in Genesis 2.

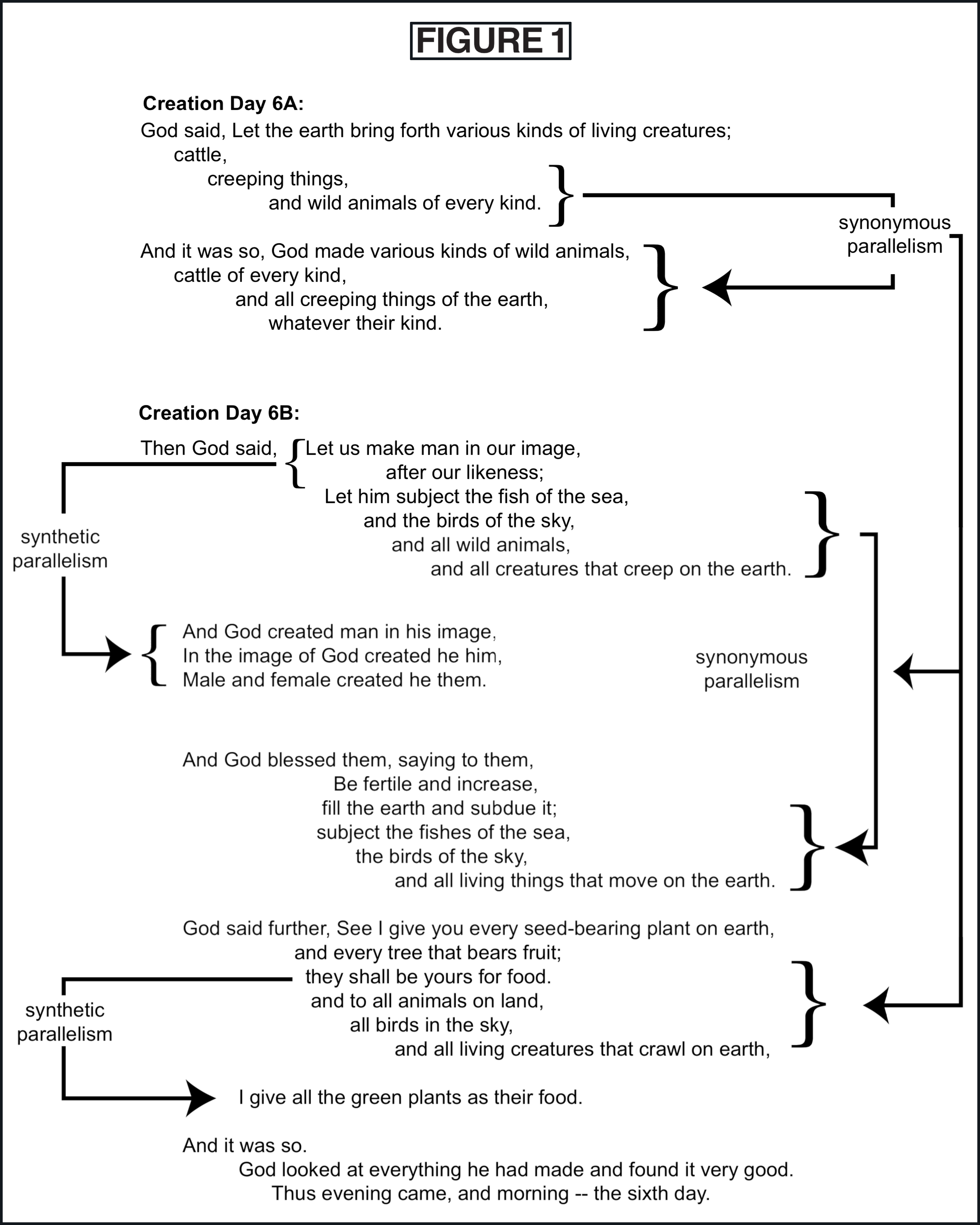

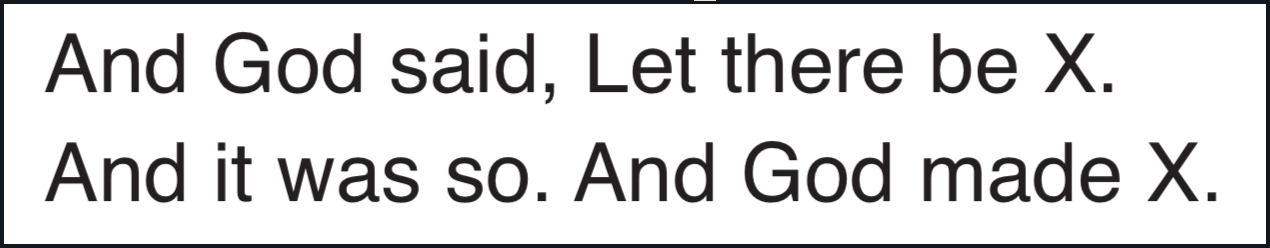

Since the content of the record for the sixth day of creation is of particular interest to us here, its literary structure deserves examination in more detail. That structure is outlined in translation in Figure 1.

I would like to emphasize the basic parallelism of the record of the sixth day of creation. This parallelism has come about through the way in which this record and those of the other days of creation are structured. These entries begin with a statement of divine intent followed by a statement of divine accomplishment, both of which refer to the same objects which are listed or described in essentially the same terms. The parallelism involved throughout the record of God's different creative acts is obvious.

In particular the parallelism of the sixth day can be seen first from the account of the creation of land animals. God said that the earth was to bring forth various kinds of living creatures, and then the text states that He made the various kinds of creatures involved. Both statements are elaborated with a very similar list, which shows the parallelism of this portion of the account.

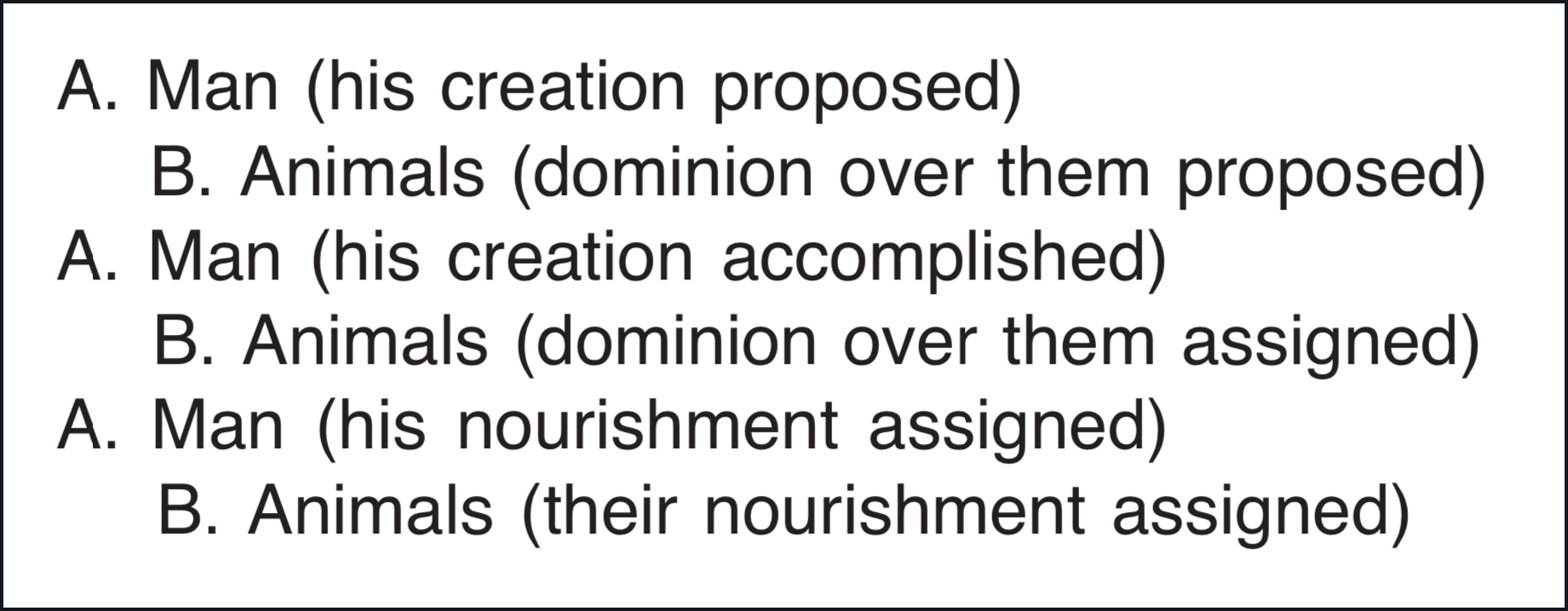

The structure of the record of the creation of man is a little more complicated. It begins with the statement of divine intent, "Let us make man," and is paralleled by the record of God's accomplishment of that intent in verse 27. Yet, in between these statements of intent and accomplishment is a statement of purpose that man was to have dominion over the animals. This in turn is paralleled by another statement concerning that dominion that it was assigned to man after he was created. Finally, this section concludes with two statements regarding food for man and food for the beasts, which again are in parallel as far as overall intent is concerned. Thus this section of the record of the sixth day of creation goes through three cycles which may be designated thematically as A:B::A:B::A:B.

Thus the basic parallelism in thought content of the record of the sixth day of creation in particular is well established, even though it is not put in precisely poetic form except for the statement concerned with the creation of man in verse 27 (see below). As has already been noted, a considerable amount of the parallelism involved in this chapter comes from the repetition of lists of things created on each of the days of creation respectively. The record of the creation of man bears a relationship to these lists in one sense that is not immediately apparent, for a list occurs in this case also, i.e., the nature of mankind is elaborated in more detail with a short list containing its two members male and female.

B. Is Genesis One Prose or Poetry?

The answer to this question is of some importance because it has been argued since the last century that the account of creation in the first chapter of Genesis was poetic and need not therefore be expected to convey historically accurate information about God's creative activity. As an artistic and aesthetic piece of literature so this argument goes this story was only intended to convey general truths about God and not a history of His mighty acts. With the attention currently being given by scholars to archaic or pre-Psalter poetry this argument has now become outmoded. Considerable stress has recently been placed upon endeavoring to reconstruct history from these old poems and they are now commonly considered older than the prose accounts which accompany them [3]. In fact, if one does consider the first chapter of Genesis to be poetry it would be extremely difficult, from a critical point of view, to assign it to so late a source as P (6th century), as some have suggested, because all the other poems in the Pentateuch (Genesis 49; Exodus 15; Numbers 23-24; Deuteronomy 32-33) are now generally considered to be pre-monarchic, i.e., from the second millennium B.C.

To answer the question of whether Genesis 1 is prose or poetry we will look first at the two lines of evidence which suggest that it might be poetry formulaic language and parallelism and then we will look at that line of evidence which suggests that it is not poetry meter.

- Formulaic language. Five phrases are used repeatedly through most or all of the entries for the days of creation: 1) "And God said," 2) "Let there be X," 3) "and it was so," 4) "and God saw that it was good," and 5) the datelines. Four of these phrases occur in all six of the entries for the days of creation, the phrase "and God saw that it was good" being the exception, since it does not occur in the record for the second day. Considering the regularly repetitive use to which these phrases were put in this account they can characteristically be considered formulaic in nature, and formulaic language (supposedly characteristic of P) [4] is one feature found on occasion in Hebrew poetry (e.g., see the refrains in Psalms 42-43 and 107 and the formulaic phrases employed by the prophets such as are found in Amos 1-2). Thus one could suggest that the use of formulaic language here points in the direction of poetry, but it does not make interpreting this chapter as poetry mandatory without further support for that interpretation from other lines of evidence.

- Parallelism. The detection of parallelism in Genesis 1 is basic to interpreting this account of creation as poetry, because parallelism was one of the basic techniques practiced by the ancient Hebrew poets. Modern scholars have analyzed the types of parallelism employed by the ancients from the grammatic and thematic points of view. The grammatic analysis of parallelism sees if the grammatic elements that occur in the first colon or line of a poem's bicolon are repeated in the second colon of that bicolon. The parallelism is not complete unless all the same elements are present [5].

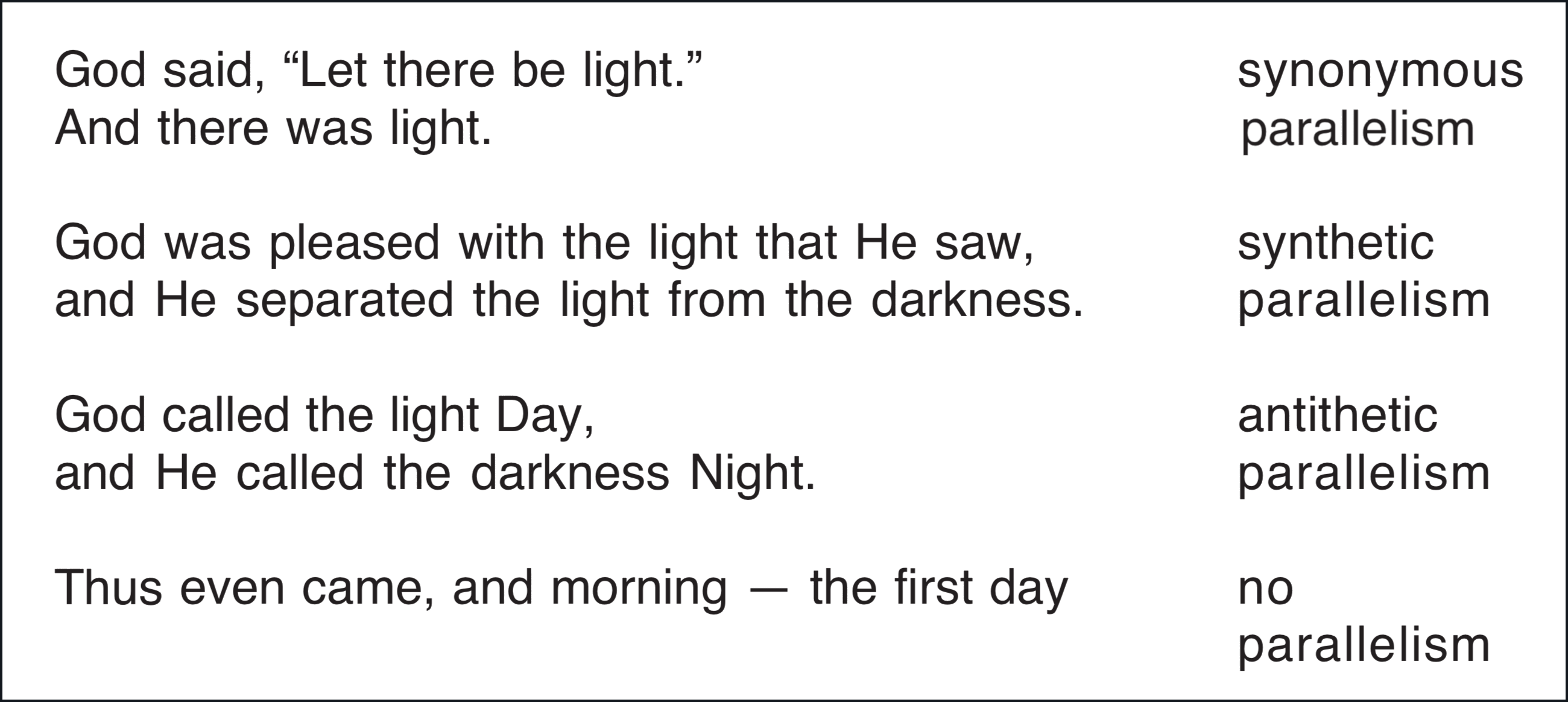

Thematic parallelism analyzes how the thought in the first colon of any bicolon in a poem is reflected in the second [6]. If the content and expression of the ideas in both cola are very similar, there is synonymous parallelism. If the cola express opposite ideas, then the parallelism is termed antithetical. Synthetic parallelism occurs when the second colon extends and complements the idea of the first colon.

All three types of thematic parallelism can be found in the account of the first day of creation: When this type of analysis is carried through all six of the entries for the days of creation, the most impressive result is that 21 cola or lines have no parallel member in the text. This large number of unparalleled cola would be very exceptional in a poetic passage but would be more natural in a prose passage.

When this type of analysis is carried through all six of the entries for the days of creation, the most impressive result is that 21 cola or lines have no parallel member in the text. This large number of unparalleled cola would be very exceptional in a poetic passage but would be more natural in a prose passage.

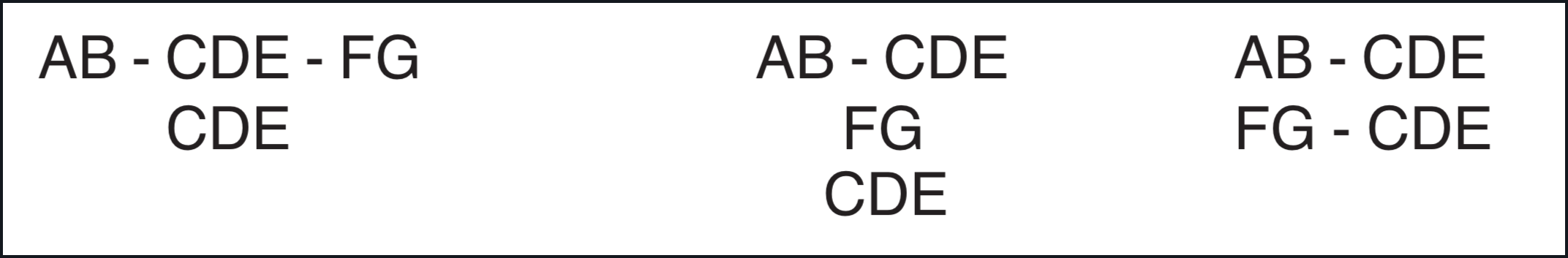

Basically, the parallelism contained in the accounts of the different days of creation follows a similar pattern: The phrase "and it was so" is difficult to locate correctly in any poetic analysis of the passages in which it occurs as it intervenes between two parallel members. Does it belong at the end of the first "colon," between the two, or at the beginning of the second? These possibilities can be outlined thematically as follows:

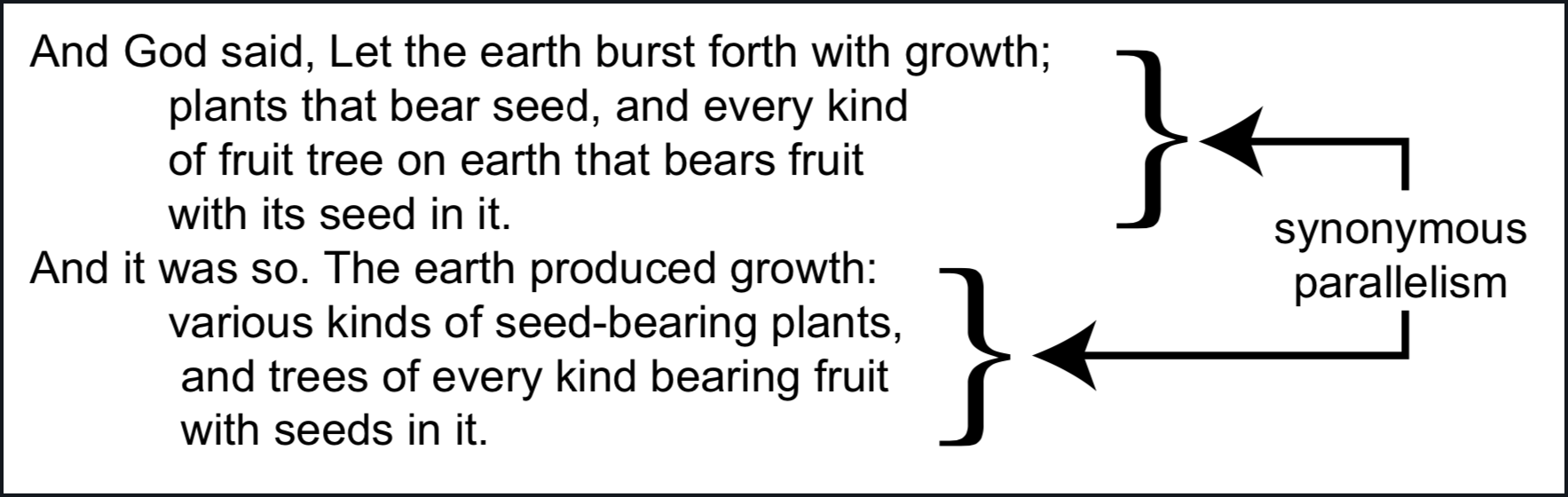

The phrase "and it was so" is difficult to locate correctly in any poetic analysis of the passages in which it occurs as it intervenes between two parallel members. Does it belong at the end of the first "colon," between the two, or at the beginning of the second? These possibilities can be outlined thematically as follows: In the first and last instances these lines would comprise a bicolon, while the middle alternative presents as a tricolon. If one attempts to analyze this chapter as poetry, then the third alternative probably is preferable, but the difficulty involved in determining the correct poetic location of this phrase, and others also, illustrate the difficulties involved in treating the whole chapter as poetry. Accepting the third alternative proposed above as most likely, however, we may proceed to a specific example of this construction from this chapter, the case of the creation of plant life on the third day.

In the first and last instances these lines would comprise a bicolon, while the middle alternative presents as a tricolon. If one attempts to analyze this chapter as poetry, then the third alternative probably is preferable, but the difficulty involved in determining the correct poetic location of this phrase, and others also, illustrate the difficulties involved in treating the whole chapter as poetry. Accepting the third alternative proposed above as most likely, however, we may proceed to a specific example of this construction from this chapter, the case of the creation of plant life on the third day. Regardless what one does with the phrase "and it was so," it is clear that the parallelism involved here relates two very long lines to each other. Excluding the two introductory statements, these two lines contain 15 and 13 Hebrew words respectively. These 15 and 13 words are in parallel with each other as units, as the parallelism involved does not lie within these units themselves. Lines of this length clearly go far beyond those commonly employed in poetry elsewhere in the Old Testament, which brings up the subject of meter. Before turning to that topic, however, the subject of parallelism might be summarized here briefly by stating that it does occur in this account in a number of instances, but in a rather rough or general way rather than in the more precise way in which it was used in poetic passages elsewhere in the Old Testament. Thus while the initial impression conveyed by the parallelism present here is that this chapter might be poetry, upon close inspection the type of parallelism employed here lends some support instead to the idea that in reality this chapter is prose.

Regardless what one does with the phrase "and it was so," it is clear that the parallelism involved here relates two very long lines to each other. Excluding the two introductory statements, these two lines contain 15 and 13 Hebrew words respectively. These 15 and 13 words are in parallel with each other as units, as the parallelism involved does not lie within these units themselves. Lines of this length clearly go far beyond those commonly employed in poetry elsewhere in the Old Testament, which brings up the subject of meter. Before turning to that topic, however, the subject of parallelism might be summarized here briefly by stating that it does occur in this account in a number of instances, but in a rather rough or general way rather than in the more precise way in which it was used in poetic passages elsewhere in the Old Testament. Thus while the initial impression conveyed by the parallelism present here is that this chapter might be poetry, upon close inspection the type of parallelism employed here lends some support instead to the idea that in reality this chapter is prose. - Meter. With a consideration of meter the suggestion that Genesis 1 is poetry really breaks down. Since more than one-third of the Old Testament was written in poetry, we have a rather extensive corpus of ancient Hebrew poetry with which to compare any meter suggested for this chapter. Modern scholars currently measure this meter by the length of the individual lines or cola. Colon length is determined in turn either by the number of words per colon (each word generally receiving one stress accent) or by the number of syllables per colon [7]. Short cola generally consist of 2 words (stress accents) or 4 to 6 syllables. Medium length cola consist of 3 words (stress accents) or 7 to 9 syllables. Long cola contain 4 to 5 words (stress accents) or 10 to 14 syllables. Cola of more than 5 words or 15 syllables are very uncommon in the Hebrew passages of biblical poetry.

In the example cited above from Genesis 1:11-12 we would have to posit two cola consisting of 19 and 17 words each in order for this passage to be considered poetry, and such cola would clearly extend far beyond the length of poetic cola found elsewhere in the Old Testament. The same holds true for other instances of parallelism that could be cited from this chapter. When judged by the standard of meter, therefore, Genesis 1 clearly is not poetry. Though not poetry in the stricter sense of the word, it does contain some poetic elements, such as the formulaic language and the general parallelisms noted above. In essence, therefore, it is prose having a poetic-like character and thus is defined accurately as poetic prose.

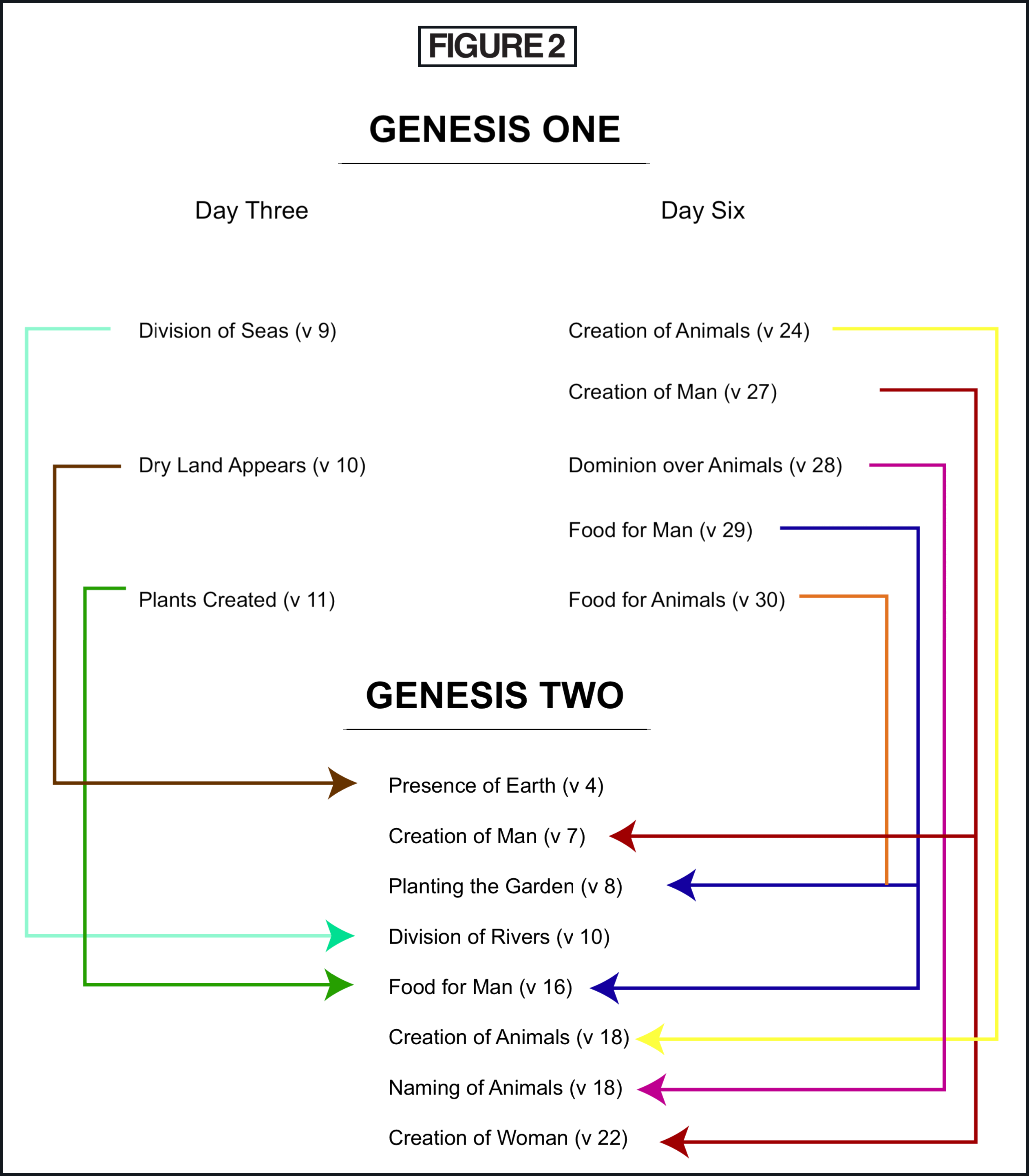

C. The Thematic Unity of Genesis One with Genesis Two

We turn now to the relationship of Genesis 2 to Genesis1. Is Genesis 2 a different source for the account of creation or is it part of the same source as Genesis 1? The more distinct Genesis 2 is from Genesis 1 by content, the more likely the first alternative is, and the more similar it is by content, the more likely the second alternative is. The creation account in Genesis 2 deals essentially with those objects to which the third and sixth days of creation were dedicated in Genesis 1: earth, plants, animals, and man; hence, it is with these two particular passages from the preceding chapter that this account should be compared. That comparison is outlined in Figure 2.

From this outline it can be seen that every major element present in the records of the third and sixth days of creation in Genesis 1 recurs in the account of creation in Genesis 2. Conversely, every major element in the account of creation in Genesis 2 is already present in the records of the third and sixth days of creation in Genesis 1, albeit in more abbreviated form. The close connection between these two accounts is readily apparent, therefore, when their contents are checked against each other. Thus what we have in the second chapter is not so much a new account of creation as it is a recapitulation of those elements already noted as created in the first chapter with added information about them.

These two accounts might also be differentiated into two different sources by their vocabularies, especially with regard to the verbs that predicate divine activity. This differentiation has been followed in the case of the verbs "create" and "make." The former is identified as the theme verb of Genesis 1 while the latter is assigned that function in Genesis 2. This differentiation of verbs between these two accounts is both artificial and inaccurate. For example, in the account of the creation of man, the verb in the statement of divine intent in Genesis 1:26 is "make," whereas the verb in the statement of divine accomplishment in Genesis 1:27 is "create." This is a poetic pair of verbs, as is evident from the fact that both "create" and "make" occur precisely eight times between Genesis 1:1 and 2:4a where these accounts are generally divided. From this it is clear that Genesis 1 is no more the chapter of the verb "create" than it is of the verb "make."

It is true that the verb "create" does not occur following Genesis 2:4a, but the verb "make" only occurs twice thereafter in contrast to the eight times it occurs in the first account of creation. This is not a contrast in verbal usage between different verbs but a contrast in the frequency of usage of all of the verbs contained in both accounts. This can be demonstrated by a further comparison of the rest of the verbs in both accounts that predicate divine activity. Aside from "make" these two chapters share only two other verbs in common. The verb "to say" is used ten times of God in the first chapter while it is used with Him as the subject twice in the second chapter. The verb "to see" is used of Him six times in the first chapter and only once in the second chapter. Notice again the contrast in the frequency of the use of these two verbs between these two chapters, just as is the case with the verb "make." Beyond these four verbs are eight others which are used for divine activity in the first chapter that do not occur in the second chapter, and a dozen verbs in the second chapter which do not appear in the first chapter.

At first glance the verbal differentiation between these two chapters might provide some support for the idea that they originally comprised two independent sources for the story of creation. However, this difference probably has more to do with the different literary characteristics of these two passages and their contents than it does with any question of sources. Genesis 1 is a skeleton sketch of the events that occurred during the seven days of the creation week and it is written in outline form using poetic prose. Considering the repetitive framework for the acts of creation recorded here it is natural that the verbs "say," "create," "make," and "see" in this account should recur frequently. The second account of creation flows on in the manner of a more standard historical narrative, providing a focused view of the events of creation that occurred on one of the seven days referred to in the first account of creation. Given the different literary characteristics of these two accounts, finding a different vocabulary in them is not unexpected. The union of these two types of writing in one harmonious whole is discussed further below.

The record of creation on the sixth day in Genesis 1 states twice that man was to have dominion over the beasts of the field. The same aspect of man's creation is emphasized in the second chapter with the description of how Yahweh brought those animals to Adam for him to name. The creation of woman, a major point in the creation account of the second chapter, is anticipated in the last colon of the tricolon in the first chapter which refers to the fact that God made both the male and female of mankind at that time. The account of creation in the second chapter is basically an elaboration upon that very point.

We might summarize the matter of the thematic unity between these two chapters by emphasizing once again the point elucidated from the outline presented above: that when those portions of the first chapter having to do with the Earth, Plants, Animals, and Man are compared with the second chapter, it is evident that they share in common virtually all of their major themes relating to those particular subjects. The fact that those major themes are elaborated in greater detail in the second chapter is only a natural consequence of the progression of the Genesis narrative and, I would suggest, did not result from collecting under one cover two originally different and possibly antithetical stories of creation derived from two independent sources.

D. The Formal Unity of Genesis One with Genesis Two

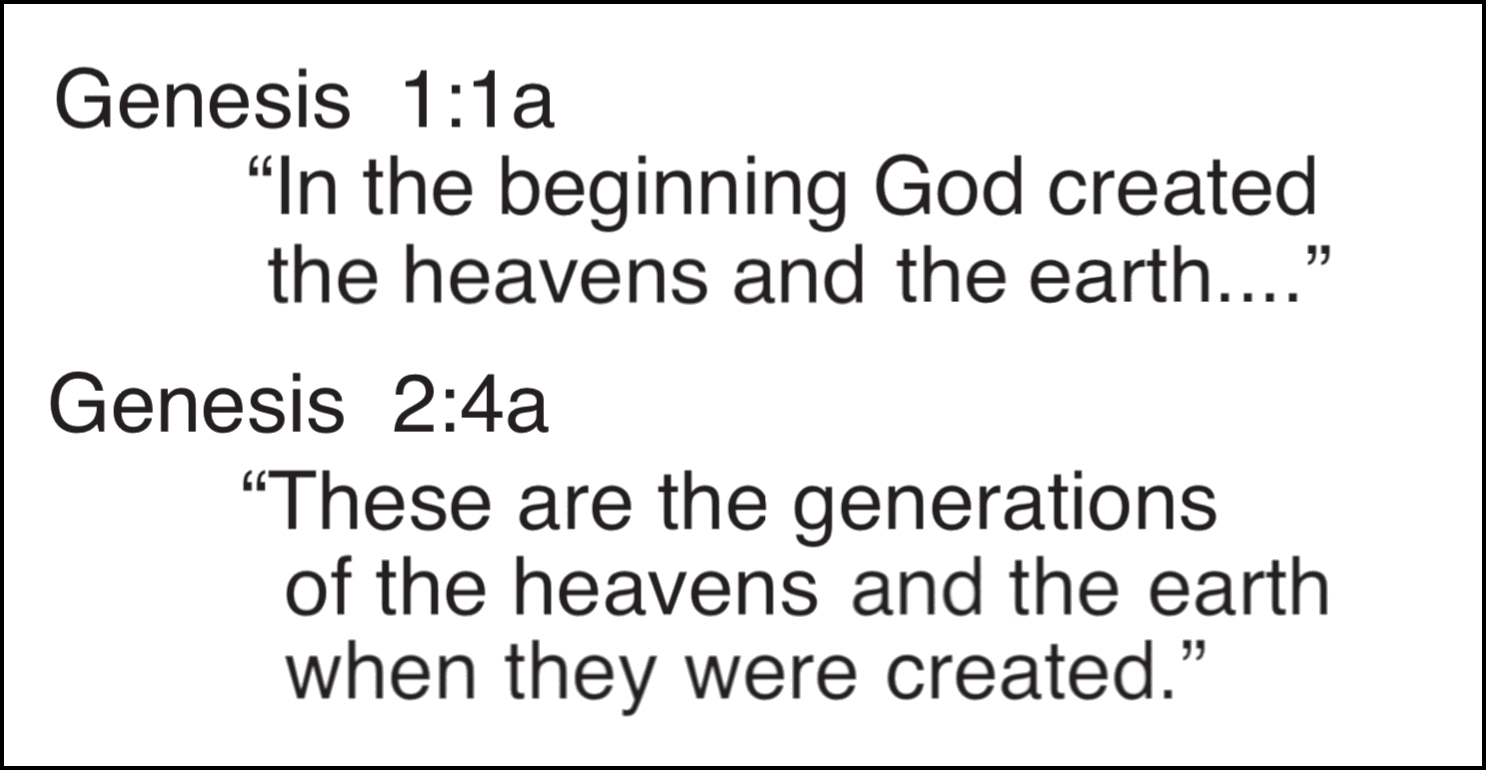

- Related at the juncture. Although traditional translations have divided these two accounts between Genesis 2:3b and 2:4a, the division made by modern scholars between Genesis 2:4a and 2:4b may well be correct. Working from that premise we may note the very precise relationship of the end of the first account to the commencement of the second account. Before discussing that relationship, however, we should note the relationship of the opening statement of the first account of creation to its closing statement:

These two statements share four elements in common while two elements differ. The common elements are the preposition "in," translated "when" in the second statement, the pair of "heavens and earth" and the verb "create." "Beginning" and "God" in the first statement are missing from the second statement while "these" and "generations" in the Genesis 2:4a statement are missing from Genesis 1:1a. Given the close relationship between the contents of these two statements, a formal relationship between them can be proposed, that of an inclusion or envelope around the first account of creation. As an inclusio these two statements present an external chiasm since the preposition and verb occur at the beginning of the statement at the beginning of the account and at the end of the statement at the end of the account, where they logically belong from a poetic point of view.

These two statements share four elements in common while two elements differ. The common elements are the preposition "in," translated "when" in the second statement, the pair of "heavens and earth" and the verb "create." "Beginning" and "God" in the first statement are missing from the second statement while "these" and "generations" in the Genesis 2:4a statement are missing from Genesis 1:1a. Given the close relationship between the contents of these two statements, a formal relationship between them can be proposed, that of an inclusion or envelope around the first account of creation. As an inclusio these two statements present an external chiasm since the preposition and verb occur at the beginning of the statement at the beginning of the account and at the end of the statement at the end of the account, where they logically belong from a poetic point of view.

Next we may note the relationship of the concluding statement of the first account of creation to the opening statement of the second account. The syntax of Genesis 2:4a reverts back to precisely that of Genesis 1:1a. In the Hebrew text this order is: 1) prepositional phrase, "in the beginning/in the day," 2) verb, "created /made," 3) subject, "God/Yahweh God," 4) objects, "the heavens and the earth/the earth and the heavens." Since Genesis 1:1a is in chiasm with Genesis 2:4a as an inclusio, it follows that Genesis 2:4a is also in chiasm with Genesis 2:4b since Genesis 2:4b parallels Genesis 1:1a syntactically. The preposition and verb occur at the end of Genesis 2:4a but at the beginning of 2:4b. Heavens and earth not only occur at the end of Genesis 2:4b, in contrast to their position in 2:4a, but they have also been reversed in order here to emphasize the chiasm present. Chiasms in the Old Testament commonly occur at the center of the poems. In this case they occur at the center of the creation story, joining the two parallel accounts which go to make up the entire story. If one were to treat this juncture poetically one could say that the first creation account is tied in here with the first colon of the "bicolon." I would not press the form of Genesis 2:4 so far as to say that it is a true bicolon, but the poetic technique employed here applies regardless of whether it is found in an explicitly poetic unit or not.

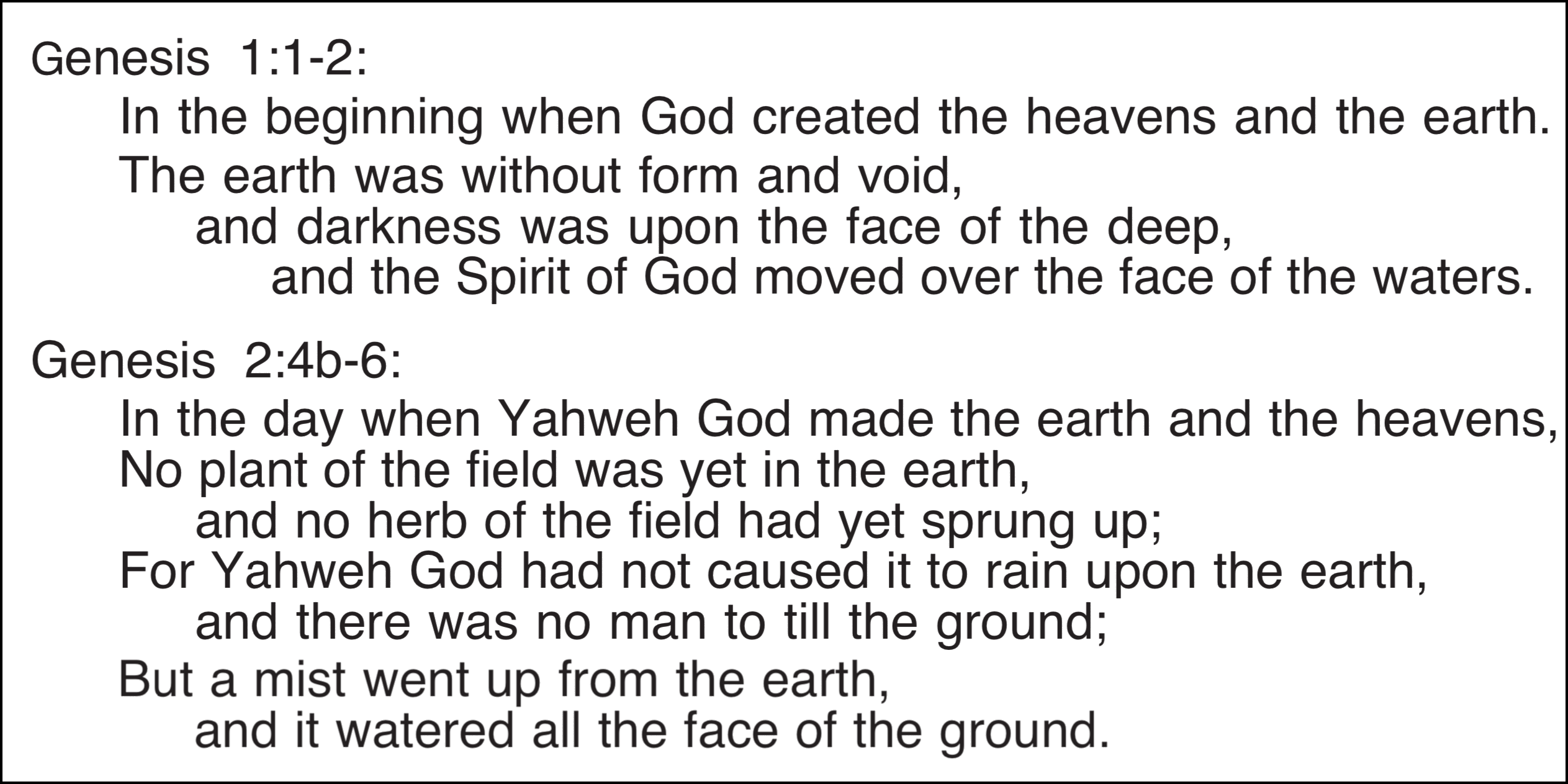

A second feature found at this literary seam also ties these two accounts together and that is the relationship of the verbs present in these two statements. The poetic pair of verbs, "create" and "make," occur together at the end of Genesis 2:3 with "create" as the A-word and "make" as the B-word. This poetic verbal pair is broken up thereafter in Genesis 2:4 with "create" as the A-word in 2:4a at the end of the first account, and "make" as the B-word in 2:4b at the beginning of the second account. Thus both the clear-cut case of chiasm and the break-up of the poetic pair of verbs present emphasize the close relationship that exists between Genesis 2:4a and 2:4b according to their form. The literary features found at this juncture draw the dividing line between these two accounts and establish connecting links between them across that dividing line. On the basis of these observations it seems fair to state that the direct ties found at the juncture between these two prose passages appear to be as strong as any similar connecting links found elsewhere in the Old Testament. - Introductory statements. Both of these creation accounts open with preliminary statements about the state of the world before it was affected by the more direct creative acts described in them. In the first chapter this statement describes the watery state of the world before the creation of light, the event most directly connected with that first delimited day. Whether there was a gap in time between what is described as occurring in Genesis 1:1 and in Genesis 1:2 is a side issue here. What is important to note is that when God went about fitting the world for man, the account presupposes that the surface of the earth was in an essentially watery state when He went about that work.

The second account of creation begins with a similar presupposition, only in this case the presupposition is that of the presence of the dry land or earth in the more specific sense of the word (Genesis 2:5). This introductory statement presupposes that a minimum of the first three days of creation in the first account preceded the events described in the second account. Thus both of these narratives begin in a similar manner, with a presupposition about the state of the earth before it was more directly affected by God's creative acts described in their respective accounts. The first account identifies that preliminary state of the earth as an aqueous one while the second account predicates the existence of dry land and plants at that point in time. The presuppositions about the state of the earth presented in these preliminary statements constitute another parallel between these two accounts of creation.

Observations on that parallel can be extended to note the form that parallel takes on here. This form can be visualized best by outlining the verse involved in translation. Although these verses are all, as far as I can see, poetic prose, they can, nonetheless, be studied along the lines of poetic analysis. Before discussing the relationship between these two passages, the internal arrangement of the second passage might be noted since it is more complicated than that of the first. If Genesis 2:4b-6 were treated as poetry it could be referred to as a title line followed by a triplet of bicola. The relations between these "bicola" can be seen in several ways. There are key words in parallel between them. The word "earth" occurs in the first line of all three. In the first instance the word "field" is linked with it and in the last two instances it alternates with "ground." God and man occur in the center of this triplet and not on either side. The emphasis at the beginning of this passage is upon the lack of plants in the field and the emphasis at the end of the passage is upon watering the ground. At the center of this passage it was Yahweh who watered the ground and man who was to till the fields which still lacked plants. But the order in the center of this triplet is Yahweh:man which is reversed so far as the elements with which they are connected are concerned, since man should precede with the fields and Yahweh should follow with the waters. This intricate pattern can be expressed as A:A::B:A::B:B.

Although these verses are all, as far as I can see, poetic prose, they can, nonetheless, be studied along the lines of poetic analysis. Before discussing the relationship between these two passages, the internal arrangement of the second passage might be noted since it is more complicated than that of the first. If Genesis 2:4b-6 were treated as poetry it could be referred to as a title line followed by a triplet of bicola. The relations between these "bicola" can be seen in several ways. There are key words in parallel between them. The word "earth" occurs in the first line of all three. In the first instance the word "field" is linked with it and in the last two instances it alternates with "ground." God and man occur in the center of this triplet and not on either side. The emphasis at the beginning of this passage is upon the lack of plants in the field and the emphasis at the end of the passage is upon watering the ground. At the center of this passage it was Yahweh who watered the ground and man who was to till the fields which still lacked plants. But the order in the center of this triplet is Yahweh:man which is reversed so far as the elements with which they are connected are concerned, since man should precede with the fields and Yahweh should follow with the waters. This intricate pattern can be expressed as A:A::B:A::B:B.

The relationship between Genesis 1:1-2 and Genesis 2:4b-6 is best seen quantitatively. If Genesis 1:1-2 were treated as poetry it could be referred to as a title line followed by a tricolon. From the same point of view the pattern of a title line followed by a triplet of bicola has been suggested for Genesis 2:4b-6. Both of these passages commence with title lines whose similarities by content and syntax have already been noted, and they continue with a "tricolon" and a triplet of "bicola" respectively. The difference between the former and the latter form is a total of three lines, the triplet of bicola containing twice as many "cola" or lines as the tricolon. This is appropriate numerically since at this point we commence the second account of creation. For a similar numerical device in terms of the number of units present see the comparison of Genesis 1:27 with Genesis 2:23 below. If the analysis of this pattern is correct, it could hardly have come about in any other way than by the design of a single author. Note also the similarity in phraseology, especially in the concluding phrase. Genesis 1:2 ends with a reference to the "face of the waters" whereas Genesis 2:6 ends with a reference to the "face of the ground," and each of these phrases describes the state of the earth at the point in time immediately prior to the creative acts which are described thereafter. - Complementary statements. At some points where these two accounts touch upon the same topic those topics are treated in similar or complementary ways. The diet assigned to man, for example, is mentioned in both accounts and in both cases it is found in direct discourse from God. That being the case, these two quotations can easily be fitted together:

And God said, "Behold, I have given you every seed-bearing plant on earth and every tree that bears fruit. They shall be yours for food (Genesis 1:29a).... You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die (Genesis 2:16-17)."

In both of these passages man was instructed that he could eat from "every" (Heb. kol) fruit-bearing tree, but in the second instance he was prohibited from eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, a more detailed specification elaborated in the second account. In a more general sense, as discussed above, man's dominion over the animals is common to both accounts. It occurs twice in parallel statements in the record of the sixth day in the first account, initially as a statement of purpose and then as a statement of that which was accomplished. That dominion is defined even further in the second account when the animals were brought to man to be named by him, thus initiating man's suzerainty over his subjects in the animal world. - Parallel pairs. Considerable stress was placed above upon the parallels present in the first account of creation. These parallels appear at three principal points on an ascending scale of larger and larger literary units: 1) within the record of each day parallel phraseology was employed for the statements of divine intent and accomplishment, 2) God's creative acts or the objects created or distinguished as a result of those acts appear in pairs on each of the days of creation, and 3) there are broader parallels between the events or objects of the first three days of creation when they are compared with the last three.

Given these parallels in the first account of creation the question arises, what is in parallel in the second account? The parallelism in the case obviously stems from the pair whose creation is described here, Man and Woman. Those elements which merely constituted a list in the first account male and female are now brought into a picture of personhood through the more direct account of their individual creation. This pair also forms an inclusion or envelope around the second account of creation, since it begins with a description of the creation of man and closes with a description of the creation of woman. Between these two poles this account describes the provisions made for this pair: their home, their diet, and their companions in the animal world. This parallel pair from the second account of creation, the most important pair of all, can now be outlined with those from the first account.

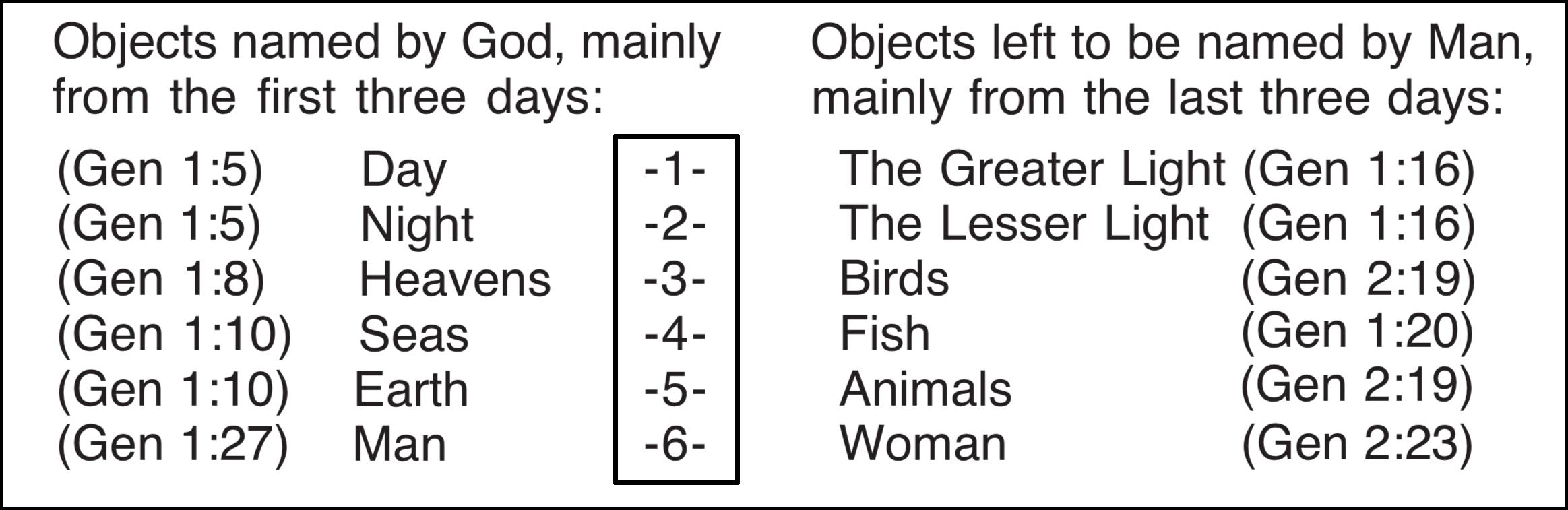

- The assignment of names. The entries for the first three days of creation in Genesis 1 contain five instances in which God himself named the objects He created: day and night, heaven(s), seas, and earth. After naming these mainly inorganic aspects of His creation, God ceased to name the objects that He created in the following three days. Basically, God ceased to assign names, with the exception of man, after He began making organic or living forms.

This distinction in the text raises the question of why God ceased to name the objects after the first three days. Genesis 2 tells us that God specifically reserved the task of giving names to that part of His creation for man. That intention, implicit in Genesis 1, is spelled out in detail in Genesis 2. This reciprocal relationship between that aspect of these two narratives applies down to almost the same number of things that were named by God and the number of things left by God for man to name, as the following outline demonstrates: It appears to me that the relatively even distribution of the names assigned by God and man to the objects created in these two accounts could only have come about by design, i.e., the original design of the Creator and secondarily by the design of one author who recorded both of these accounts of creation together as complementary to each other. So specifically complementary is this aspect of these two narratives that it seems unlikely in the extreme that such a distribution of this kind of activity could have come about by chance through the preservation and collection of two separate, distinct, and originally independent stories of creation. This design even transcends the extent of literary activity that one could normally attribute to an editor. Thus the distribution of the names assigned to the objects of creation stands as a strong argument for the unity of these two accounts on the basis of form.

It appears to me that the relatively even distribution of the names assigned by God and man to the objects created in these two accounts could only have come about by design, i.e., the original design of the Creator and secondarily by the design of one author who recorded both of these accounts of creation together as complementary to each other. So specifically complementary is this aspect of these two narratives that it seems unlikely in the extreme that such a distribution of this kind of activity could have come about by chance through the preservation and collection of two separate, distinct, and originally independent stories of creation. This design even transcends the extent of literary activity that one could normally attribute to an editor. Thus the distribution of the names assigned to the objects of creation stands as a strong argument for the unity of these two accounts on the basis of form. - Prose and poetry. Although Genesis 1 is not poetry per se, it contains one small piece of poetry towards the end of the chapter, the tricolon in verse 27 which refers to the creation of man.

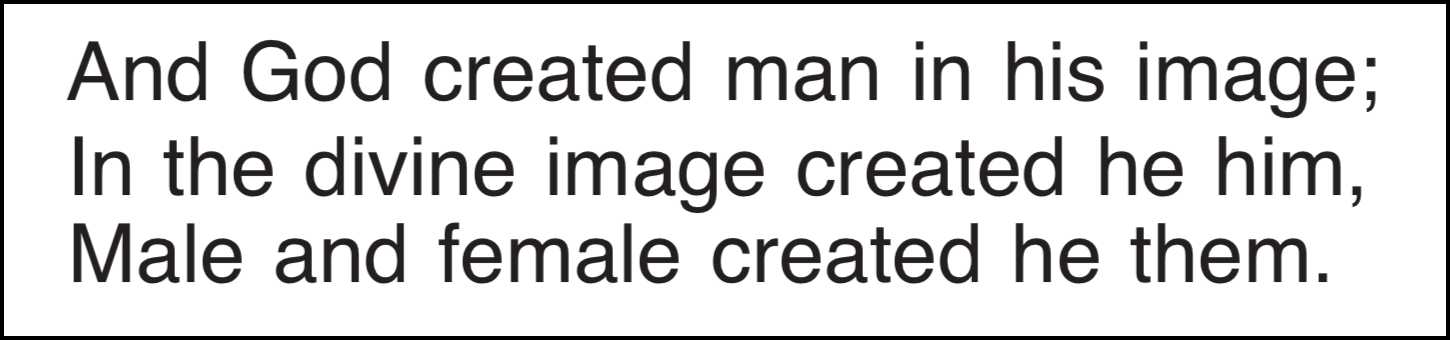

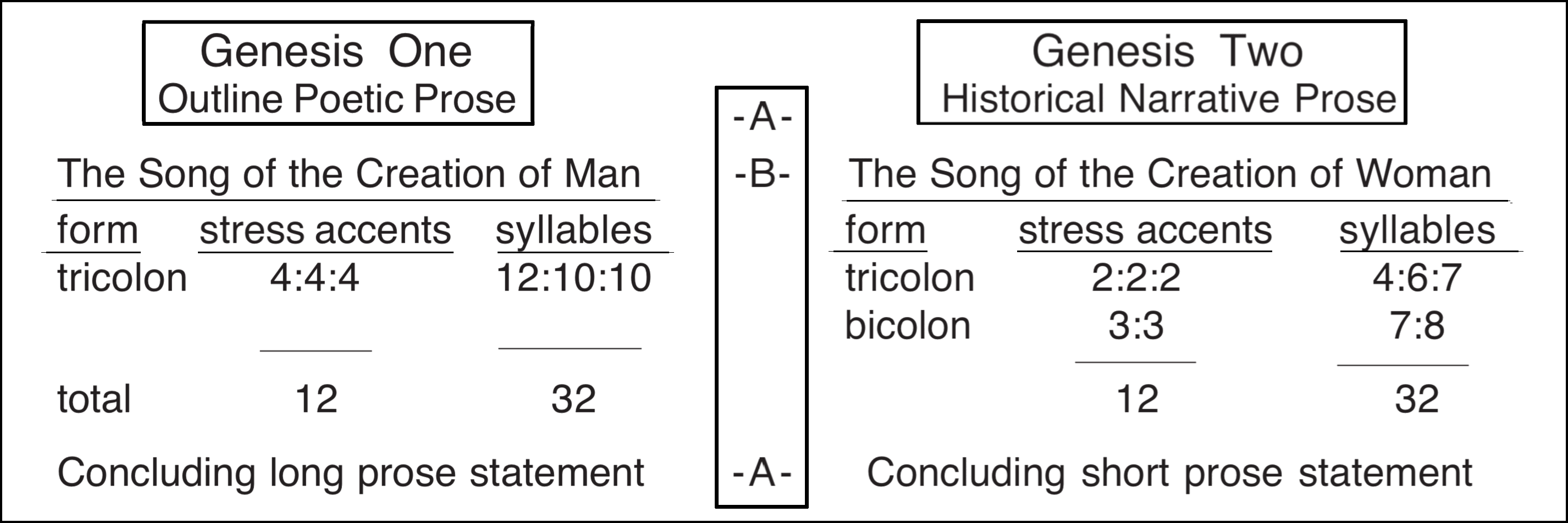

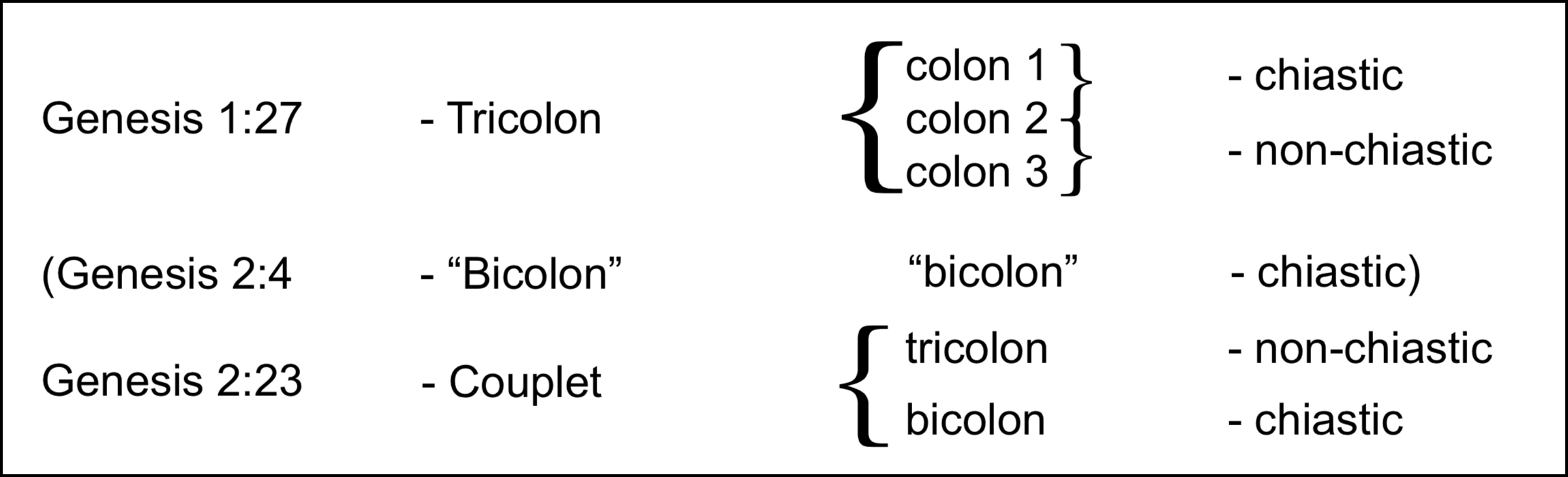

The poetic character of this verse is clearly evident from its meter, which is 4:4:4 in terms of words or stress accents in the Hebrew text (or 12:10:10 by syllable count). The parallelism between the first two cola of this tricolon is complete and chiastic. The parallelism between the second and third cola of this tricolon is incomplete, the word for female in the latter having replaced the word for God in the former. All three cola of this tricolon employ the same verb for "create," and they all end with pronouns. This brief piece of poetry is preceded by a long prose passage and it is followed by a short prose passage. Thus the overall literary structure of Genesis 1 can be outlined as prose:poetry:prose, or A:B:A.

The poetic character of this verse is clearly evident from its meter, which is 4:4:4 in terms of words or stress accents in the Hebrew text (or 12:10:10 by syllable count). The parallelism between the first two cola of this tricolon is complete and chiastic. The parallelism between the second and third cola of this tricolon is incomplete, the word for female in the latter having replaced the word for God in the former. All three cola of this tricolon employ the same verb for "create," and they all end with pronouns. This brief piece of poetry is preceded by a long prose passage and it is followed by a short prose passage. Thus the overall literary structure of Genesis 1 can be outlined as prose:poetry:prose, or A:B:A.

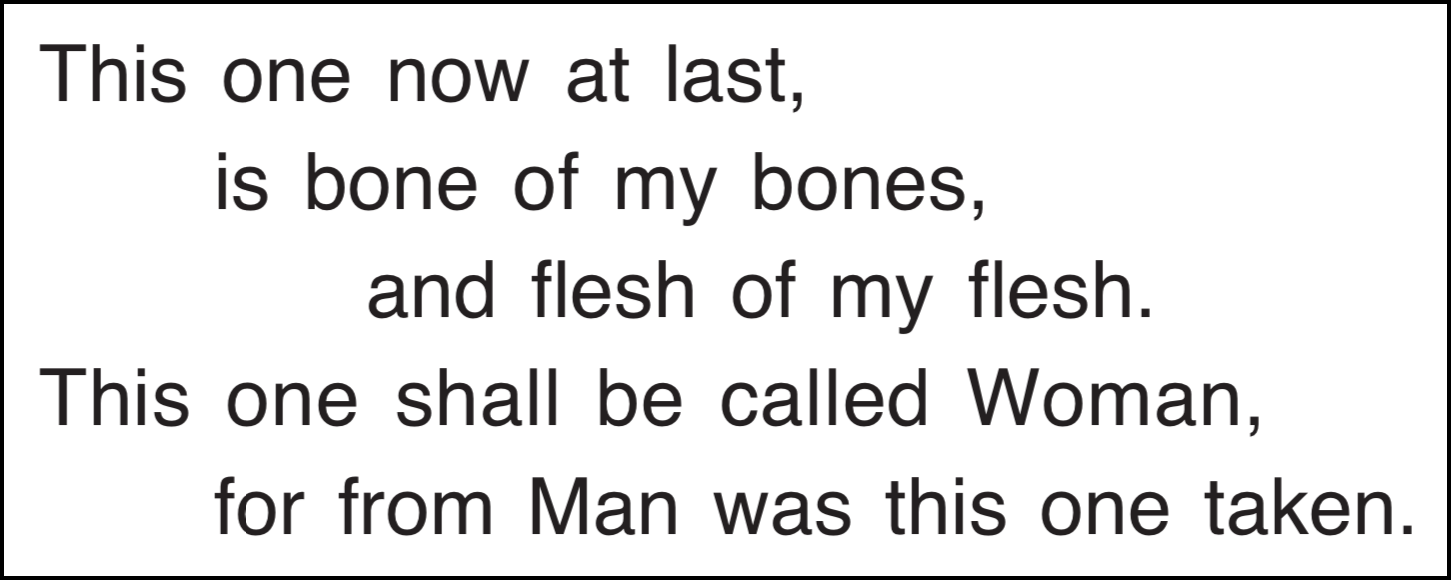

The literary structure followed in the second account of creation is the same A:B:A form. This is evident from the fact that Adam's response in Genesis 2:23 to the creation of Woman is recorded, as recognized by the RSV for example, in poetry: In terms of the larger poetic units, this verse consists of a couplet which contains a short-line tricolon followed by a long-line bicolon. The cola in the opening tricolon of this couplet contain two words each in the Hebrew text, which yields a meter of 2:2:2 in terms of stress accents or 4:6:7 in terms of their syllable counts. The second and third cola of this tricolon are of particular interest since they contain partitive cognates, meaning that both of the words in each of these cola, bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh, come from the same noun, an obvious poetic device. Taken together bone and flesh are in synthetic parallel with each other as they refer to different parts of the body. The letter M is used in Hebrew for the prefixed preposition "from"; consequently, this letter provides a recurrent or alliterative sound in this tricolon. It occurs once in the opening colon, once in the closing colon, and three times in the central colon of this tricolon.

In terms of the larger poetic units, this verse consists of a couplet which contains a short-line tricolon followed by a long-line bicolon. The cola in the opening tricolon of this couplet contain two words each in the Hebrew text, which yields a meter of 2:2:2 in terms of stress accents or 4:6:7 in terms of their syllable counts. The second and third cola of this tricolon are of particular interest since they contain partitive cognates, meaning that both of the words in each of these cola, bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh, come from the same noun, an obvious poetic device. Taken together bone and flesh are in synthetic parallel with each other as they refer to different parts of the body. The letter M is used in Hebrew for the prefixed preposition "from"; consequently, this letter provides a recurrent or alliterative sound in this tricolon. It occurs once in the opening colon, once in the closing colon, and three times in the central colon of this tricolon.

The parallelism present in the long-line bicolon with which this couplet concludes relates the Woman in the first colon to the Man in the second colon, two words which consist of very similar sounds in Hebrew as they do in English. A chiasm is present in this bicolon since its first colon opens with the word for "this" and the second colon closes with the same word. In addition, Woman occurs at the end of the first colon while Man occurs at the beginning of the second. Thus this bicolon can be outlined thematically as A:B:C:B:C:A, a good example of chiasmus. The word "this" also links the opening tricolon to the closing bicolon since it is also the first word in the opening colon of the tricolon. The meter of the closing bicolon of this couplet is 3:3 as it stands in the Hebrew text with the last two words of the second colon joined by a maqqeph, a marker which joins these two words like a hyphen in English writing. The syllable count of this bicolon is 7:8.

With the poetic character of this verse established, we can now compare it with the tricolon found in the first account of creation. The results of the comparison can be outlined as follows: To emphasize further the relationship between these two brief poetic pieces, it may be noted that when they are compared directly with each other their chiasms occur in chiastic order. Thus the order of this particular element between these two poetic pieces is chiasm:non-chiasm::non-chiasm:chiasm, or A:B::B:A, which is a chiastic construction in itself.

To emphasize further the relationship between these two brief poetic pieces, it may be noted that when they are compared directly with each other their chiasms occur in chiastic order. Thus the order of this particular element between these two poetic pieces is chiasm:non-chiasm::non-chiasm:chiasm, or A:B::B:A, which is a chiastic construction in itself.

At this point I would like to refer back to the discussion of the features of the juncture between these two accounts located in Genesis 2:4. In the discussion of that juncture it was noted that another chiasm can be seen when Genesis 2:4a and 2:4b, the last line of the first creation account and the first line of the second, are compared with each other. Although Genesis 2:4 probably is not poetry in the more precise sense of the word as Genesis 1:27 and 2:23 are, it can be included in the outline that follows with these other two verses since the same literary technique is demonstrated in it. It seems very unlikely to me that the A:B:A forms followed in both of these chapters and the exact metrical correspondence between the more precise poetic pieces present in both of them could have come about in any other way than by direct intent or design. Once again, the intricate nature of this design, especially as concerns the directly poetic elements, goes beyond that which one could conceivably attribute to an editor and must be traced back to the original author of both of these narratives. The strong implication of these correspondences is that both of these accounts of creation were originally written down by the same author without much of a time lag between the occasions when they were composed, not by different authors separated by several centuries.

It seems very unlikely to me that the A:B:A forms followed in both of these chapters and the exact metrical correspondence between the more precise poetic pieces present in both of them could have come about in any other way than by direct intent or design. Once again, the intricate nature of this design, especially as concerns the directly poetic elements, goes beyond that which one could conceivably attribute to an editor and must be traced back to the original author of both of these narratives. The strong implication of these correspondences is that both of these accounts of creation were originally written down by the same author without much of a time lag between the occasions when they were composed, not by different authors separated by several centuries. - Parallelism of larger literary units. We have already concluded that Genesis 1 was poetic prose, i.e., prose written in a quasi-poetic style. With the exception of verses 4b-6 (poetic prose) and verse 23 (poetry), however, Genesis 2 was written in more normal narrative prose. For the purposes of this discussion the poetic aspect of Genesis 1 is emphasized in contrast to the prose of Genesis 2, even though Genesis 1 is not poetry in the stricter sense of the term. One might wonder if there are any parallels to such a relationship elsewhere in the Bible or outside of the Bible in terms of more lengthy literary units like these two chapters. That question can be answered in the affirmative from both sources.

Other sections of the Pentateuch reveal similar poetry/prose patterns. The poem found in Genesis 49, the Testament of Jacob, is both preceded and followed by prose passages that provide a context for it. The pattern of prose and poetry involved in this case takes on the A:B:A configuration to which we have referred previously.

The prose account of the deliverance of the Israelites from Pharaoh's host is found in Exodus 14 while the poem celebrating that deliverance appears in Exodus 15. The pattern in this case is thus simply A:B. The Oracles of Balaam in Numbers 23-24 have a more elaborate arrangement. Instead of one large block of poetry set beside one or two blocks of related prose, smaller blocks of poetry are interspersed in a prose narrative. Four different poems from Balaam occur in this narrative and the whole episode ends with the last of those poems so that the pattern is A:B::A:B::A:B::A:B. It would be difficult to separate these poems of Balaam from the prose narrative in which they are found and still make good sense out of them, which shows the intimate relationship between prose and poetry.

The famous covenant lawsuit poem of Deuteronomy 32 conveys the blessings or curses predicated of Israel contingent upon its obedience or disobedience. The same blessings and curses already appear, however, in prose passages beginning with Deuteronomy 28, making a pattern of A:B. The Testament of Moses found in Deuteronomy 33 is followed by the prose passage in chapter 34 which tells of the circumstances of his death, making a pattern of B:A. Thus the two great poems at the end of Deuteronomy were located back-to-back with their related prose passages on either side of them.

The first of the old poems encountered following the Pentateuch is the Song of Deborah in the book of Judges. The story of the battle and the circumstances leading up to it is found in prose in Judges 4 while it is commemorated in poetry in chapter 5. The pattern here is thus A:B, the same as that found in Exodus 14-15 which also celebrates a victory over the enemies of God's people. Some scholars have tried to separate these two sources rather widely from each other in time and point of view. I would suggest, however, that a clear picture of the topography and strategy involved in the battle described in these two passages can only be derived from a combination of the historical data available in both of these sources. To the extent to which that suggestion is correct it would show the complementary nature of these two sources and, therefore, their close literary relationship.

The message of the Song of Hannah in 1 Samuel 2 is explained in the preceding chapter of prose and is also related less directly to the fate of Samuel as a child that is described in what follows. An understanding of David's Lament in 2 2 Samuel 1 is dependent upon a knowledge of the events described in the prose of 1 Samuel 31. The Songs of David in 2 Samuel 22-23 appear to be the only pre-Psalter poems that stand in a rather isolated position from the prose context surrounding them. On a larger scale one might cite the example of the book of Job in which the classic A:B:A pattern spans the entire book, with the frame story in prose serving as an envelope around the dialogues in poetry.

To summarize our findings from this review of the relationship between prose and poetry in pre-Psalter sources we may note that in 9 out of 11 cases studied the poetry involved related rather directly to the prose passages connected with them, the exceptions being 2 Samuel 22 and 23. In four of these cases that relationship may be expressed as A:B (Exodus 15, Judges 5, Deuteronomy 31, and 2 Samuel 1). In three cases the relationship present is A:B:A (Genesis 49, 1 Samuel 2, and Job). One case presents the pattern of B:A (Deuteronomy 33), while another was written in the more complex pattern of A:B::A:B::A:B::A:B (Numbers 23-24). It may be said, therefore, that there are a number of biblical parallels for pairing larger literary units of prose with poetry as we have suggested for Genesis 1 and 2 in a more general sense.

Critical scholars who dispute the prose/poetry relationship employ the a priori assumption that the prose account must have been composed later, frequently much later, than the poems involved. The question here is, were the prose accounts in these cases written down much later than these poems or were they both written down relatively contemporaneously?

One way in which this subject can be investigated is to look for prose/poetry combinations in the literature of Israel's neighbors in the ancient world. If such pairs are found, then there is no particular reason why we should deny the possibility that the Israelites were capable of creating the same type of literary constructions at the same time or later than their neighbors were. From a very brief survey of this subject which was far from exhaustive it appears to me that this type of writing was employed in Egypt in particular, in contrast to Mesopotamia where examples of it are rare. This Egyptian context for this type of writing is of some interest since half of the old poems considered above come from the Pentateuch and accepting a Mosaic authorship for that section of the Scriptures would indicate that the author or recorder of these poems with their related prose passages was educated at the court in the land where this type of writing was done.

The use of the prose-poetry type of literary construction goes back at least as early as the time of the sixth Egyptian dynasty late in the third millennium B.C. A description of military expeditions into Palestine begins with a long prose passage, then shifts to a poetic passage consisting of seven bicola with refrains, and concludes with another shorter passage of prose [8]. The identification of the poem in this inscription as a victory poem puts it in the same class of texts as that to which the Song of the Sea (Exodus 15) and the Song of Deborah (Judges 5) belong.

A victory hymn of Thutmose III (1504-1450 B.C.), the general period during which Moses lived in Egypt, employs the same type of literary construction as described above [9]. A more complicated pattern of A:B::A:B::A:B::A:B::A:B [10] appears in Merneptah's Victory Stela (ca. 1225 B.C.) which contains the first reference to Israel outside of the Bible.

Some literary pieces from the First Intermediate Period just before 2000 B.C. reflect the political chaos of the time. One text, "A Dispute over Suicide," describes the argument of a man with his soul about whether to commit suicide. At the end of the dispute he agrees to remain with man. The text begins with a long prose introduction, continues with a poem consisting of 32 tricola employing 4 refrains, and ends with a shorter prose conclusion [11] or, A:B:A.

The second text from this period for consideration here records the story of a peasant whose nine eloquent speeches at the king's court convinced his hearers to execute justice on his behalf. The literary frame for this story opens with a long prose introduction and ends with a shorter prose conclusion. Since the central cycle of this piece alternates 9 times, its structure is A:B(x9):A [12], and the form of his work has been compared with that of the book of Job.

Other Egyptian pieces show similar structures. A building inscription of Amenhotep III (1413-1377 B.C.) has the simple structure A:B [13]. The 125th chapter of the Book of the Dead which was in use in the latter half of the second millennium and the first half of the first millennium gives an A:B:A:B:A structure [14]. The Instructions of Amenomopet, resembling biblical proverbs in some respects, begins with a lengthy prose prologue which is followed by 30 short chapters of instructions in written poetry [15].

One of the better examples of this type of literary construction from Mesopotamia is found in the Code of Hammurabi. This inscription begins with a poetic prologue which is followed by 282 stipulations written in legal prose and then concludes with a poetic epilogue [16]. The structure here is the reverse of that seen more commonly, B:A:B. The legal prose in this inscription probably has a longer tradition behind it than the poetry present in the prologue and epilogue, since these laws are considered to represent the cumulation of common practice rather than de novo legislation or decrees issued by Hammurabi [17]. From the very late (Seleucid) period of Babylonian history come four texts which describe temple rituals [18]. The rituals to be performed are outlined in prose but the prayers to be recited during those rituals were written in poetry; so these texts have structures of A:B, A:B:A, A:B(x6), and A:B(x7):A respectively.

With the possible exceptions of the Book of the Dead and the Seleucid temple rituals, it would be difficult to argue in any of the above cases that the prose passages present in these cases were first recorded in written form at a time much later than the poems present with them in the surviving copies of these texts. To my knowledge, no Egyptologist (or Assyriologist) has expressed himself in favor of such a viewpoint on the composition of these texts. Thus there is a basic dichotomy between biblical studies and ancient Near Eastern studies when it comes to the way in which texts that contain these combinations of prose and poetry are treated. Biblical scholars say the prose passages were always written down later than the poems found with them, while specialists in ancient Near Eastern studies generally consider such combinations in texts with which they deal to be essentially contemporaneous.

Since these texts came from the world in which the Israelites of the Bible did their writing, it seems appropriate to take into consideration the form in which contemporary compositions were written in the world around them. Examination of such compositions indicates that poetry was written with prose in the same pieces at the same time, hence it seems rather arbitrary of the critic of biblical literature to deny that such could have taken place in Israelite circles. It is also evident from these considerations that there was a long-standing tradition of such combined compositions both in the pre-Psalter portions of Scripture and in extra-biblical texts from the same period. The combination of "poetry" and prose in Genesis 1 and 2 adds another example to the list of such parallels on the larger literary scale.

E. Summary

Parallelism is found in Genesis 1 on three levels: 1) within the record of each day parallel phraseology was employed for the statements of divine intent and accomplishment, 2) God's creative acts or the objects created or distinguished as a result of those acts appear in pairs on each of the days of creation, and 3) there are broader parallels between the events or objects of the first three days of creation when compared with the last three. Along with the formulaic language used in this chapter, these parallels might at first convey the impression that this chapter was written in poetry. It soon becomes evident that this initial impression is incorrect, however, when the matter of meter is taken into account. The exceptionally long lines one would have to posit here to interpret this chapter as poetry clearly indicate that it is prose instead, but prose which was written in a quasi-poetic style. Although Genesis 1 was written in prose, it contains one clear-cut example of poetry, the tricolon in verse 27 which I have entitled, "The Song of the Creation of Man." It is more evident that Genesis 2 was written in prose, but it too contains one clear-cut example of poetry, the couplet in verse 23 which I have entitled "The Song of the Creation of Woman."

The unity present between these two accounts of creation can be demonstrated through two main avenues, by theme and by form. As far as theme is concerned, it is evident from our examination of these two narratives above that every major theme found in Genesis 2 is already present in Genesis 1, albeit in miniature, especially in the records of the third and sixth days of creation. The formal unity of Genesis 1 with Genesis 2 can be demonstrated in a number of ways:

- They are related at the juncture between Genesis 2:4a and 2:4b by the chiasm which occurs across this juncture and by the break-up of the poetic pair of verbs which occurs here.

- They are related by the nature of the introductory statements found at the beginning of both of the accounts of creation which present a presupposition about the state of the earth, whether covered with water or consisting of dry land to some extent, prior to the creative acts described in what follows these introductory statements.

- In some cases statements referring to the same created objects in these two accounts are given in rather similar and thus complementary terms.

- Genesis 1 presents precisely six parallel pairs of creative acts or created objects, one pair for each of the six days. Genesis 2 fills out this list of parallel pairs with the final and most important pair, Man and Woman. This pair was already referred to in Genesis 1 with the list elaborating the creation of Man into male and female, just as the other objects described there as created such as the plants, fish, and animals are elaborated upon with comprehensive lists.

- When it came to the task of assigning names to the objects He created, God named those things which He made on the first three days, but He left those things which He made on the next three days for man to name. Man's participation in this naming process is described in Genesis 2.

- Both of these chapters contain one brief piece of poetry, verse 27 in the first and verse 23 in the second. Both of these brief pieces of poetry are preceded by longer passages of prose and followed by shorter passages of prose, giving them both an A:B:A structure. These two pieces of poetry contain exactly the same number of stress accents and syllables and they treat a parallel theme, the creation of Man and the creation of Woman. Genesis 1:27 contains a tricolon while Genesis 2:23 consists of a couplet containing a short tricolon followed by a long bicolon. In this case the poetic piece with two units appears in the second, which again is numerically appropriate as it is in the case of the two introductory statements. Genesis 1:27 begins with a chiasm while Genesis 2:23 concludes with a chiasm, which fits a pattern that is elaborated further with the chiasm that occurs at the juncture between Genesis 2:4a and 2:4b, where these two accounts of creation divide and are joined.

- If one interprets Genesis 1 more generally as a poetic type of writing, even though it is not poetry in the technical sense of the word, then it can be coupled with Genesis 2 as a pair of "poetry" and prose. Nine biblical, eight Egyptian, and five Babylonian examples of writing which couples prose together with poetry have been cited as parallels for such a construction in the first two chapters of Genesis.

From the unity that exists between two chapters by theme, from the length of this list of the features they share in common by form, and from the intricate and detailed nature of some of these formal relationships, it seems to me that the logical conclusion to draw is that these two chapters of Genesis present an account of creation unified by intentional design. That design extends far beyond the details an editor could have touched up to join two originally independent accounts of creation. Accordingly, the composition of these two chapters containing the account(s) of creation should be attributed to a common author.

If these two accounts were written by one author, as is proposed here, the dates of their composition obviously cannot be separated by more time than the span of his literary career, and more probably they were composed around the same time in that career. If the conclusion drawn here from the features of these two accounts discussed above is correct, they cannot be attributed to J writing in the 10th century and P writing some four centuries later. In my opinion, literary critics, such as the one quoted at the beginning of this study, have come to this incorrect conclusion about these two chapters, because they have approached the text with a methodological presupposition rather than a methodology derived from the text itself. Some of the features which these critics have sorted out of these two chapters do not support the conclusions associated with them, and other details which have been overlooked contradict these conclusions.

III. THE REASON FOR THE USE OF DIFFERENT NAMES FOR GOD IN GENESIS ONE AND GENESIS TWO

With the rise of biblical criticism one criterion cited to aid in the project of sorting out the sources underlying the books of the Bible, especially of the Pentateuch and more particularly Genesis, was the different names used for the Deity. This criterion came into use more than two centuries ago, as the commentator quoted at the beginning of this study noted:

A significant milestone in the literary criticism of Genesis was the observation published in 1753 by the French physician Jean Astruc that, when referring to the Deity, some narratives in this book use the personal name Yahweh ("Jehovah"), while other and apparently parallel accounts employ Elohim, the generic Hebrew term for 'divine being.' It would thus seem to follow, Astruc argued, that Genesis was made up of two originally independent sources [19].

A common example cited for employing this criterion to sort out such sources comes from the first two chapters of Genesis where it has often been noted that the names used for God in these two chapters, attributed to P and J respectively, are different. In the first chapter Elohim is used exclusively and occurs there almost thirty times. Starting with the fourth verse of the second chapter, on the other hand, Yahweh Elohim is the only name used for God and it occurs there eleven times. This difference in reference to the Deity is used as further evidence against the Mosaic authorship of Genesis 1 and 2 [20]. Logic limits to three the interpretations available for solving the problem posed by this difference in divine names.

- This difference in divine names should be attributed to the different sources from which these two accounts originated.

- Different divine names are used in these two passages because of a mere random or chance selection of them on the part of the writer of the entire creation account.

- The names for God in these two passages differ because the writer of the creation account had a specific theological reason in mind.

The first of these theories is the standard interpretation adopted by a majority of literary critics over the last century. It achieved acceptance to some extent because it provided a relatively reasonable explanation for the data available from the text, and because no better explanation for such data was forthcoming. The second interpretation might appear to hold some appeal for a conservative commentator on Genesis, but in the end it must be rejected because it does not fit the facts of the case. If our statistical sample were small then one might argue that only a random difference was involved here, but in view of the relatively frequent occurrence of the names for God in these two passages (28:11) this explanation is unsatisfactory. The distinction is too sharp and too well attested to be attributable to chance. The third interpretation listed above is the one proposed here.

The statement in Genesis 1:26 of God's intent to make man provides a convenient point of departure in the study of this subject, since it differs in nature from the other statements of intent in Genesis 1 and it introduces the more detailed description of the creation of man in Genesis 2 where the longer name for God is introduced in the creation story. The subjects of the verbs in the initial statements of the records for the first five and one-half days of the creation week are always the objects created or the substance from which the created object issued. In the statement "Let there be light," for example, light is the subject of the verb to be. In the statement "Let the earth cause plants to spring forth," the earth is the subject of the verb to (cause to) spring forth. Not so with the record of the creation of man. If it had followed that pattern this record would have read, "Let there be man," or, "Let the earth give forth man." Instead, for the first time in these initial statements, God is the subject of the verb present, "Let us make man."

The uniqueness of this statement in contrast to its fellows in the records of the previous days of creation emphasizes the distinction intended by the author here. More than any other aspect of His creation, God was intimately involved in the creation of man. While He could speak those other aspects of creation into existence, creating man required more personal attention so that man became not only the product of His lips but also of His hands and thus of His heart. Thus this much-discussed phrase in Genesis 1:26 introduces God's direct and personal attention to and intimate involvement in the creation of man described more fully in Genesis 2. The first person plural form of the verb in Genesis 1:26 may indicate either an aspect of mutuality within the Godhead, or a plural of "fullness" [21].

In the Genesis 2 account of the creation of man we are not really dealing with a different name for God, but with a more specified name for God: Yahweh Elohim, in contrast to Elohim alone. The association of Elohim in Genesis 2 with the divine name Yahweh is something of an embarrassment to the literary critical theory. To make the contrast between a presumed Elohist source (P) and a presumed Yahwist source (J) more distinct in these chapters, the critic is obliged to suggest that the name originally present in Genesis 2 was Yahweh, and that Elohim was added to it later [22]. Not only is there no textual evidence for such a theory, but the fact that Yahweh Elohim is used only in Genesis 2 and 3 and nowhere else in the Pentateuch, with the sporadic exception of Exodus 9:30 [23], argues strongly against a later insertion of Elohim in Genesis 2. If Elohim was a later addition one would expect to see such a combination more widely spread throughout Genesis and the rest of the Pentateuch. Thus we are not dealing with the distinction between Elohim and Yahweh, as the literary critic would have it, but with the development of an increasing specification from Elohim to Yahweh Elohim.

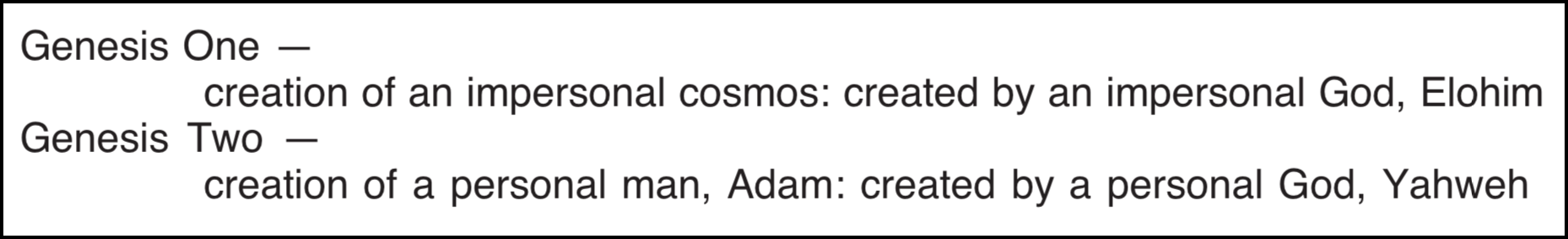

The question then is, why does the divine name take on this increasing specification in Genesis 2? It is clear that the forms El/Elim/Elohim refer to god in the generic sense and could be used for the true God or a false god, one god or many gods (in singular or plural), the Israelite God or Canaanite god(s). Thus in a certain sense Elohim is a more "impersonal" name for God, and this name is used for God when He set up an impersonal cosmos in Genesis 1. The equation for the divine name used in Genesis 1 is, therefore creation of an impersonal cosmos: created by an impersonal God, Elohim.

When we come to the creation of man in Genesis 2, however, the picture changes. With this change the name of Yahweh is introduced for God. As far as etymology is concerned, the best current suggestion probably is that Yahweh may derive from a causitive form of the verb to be. But the etymology of the name Yahweh is a side issue in Genesis 2. The really important aspect of Yahweh from the viewpoint of the author of the creation account is that this is God's personal name. The generic word for god, El/Elohim, is not nearly so specific. The name of Yahweh, however, could apply to one God only from the biblical point of view the one true God whom the Israelites worshipped. At this point in the record, therefore, the personal God Yahweh bends down to "fashion" the personal man, Adam, from the dust of the earth. The anthropomorphism involved here is obvious but is nonetheless beautiful as it expresses God's tender and loving concern for this part of His creation more than any other part of it. Thus the equation for the divine name used in Genesis 2 is creation of a personal man, Adam, and a personal woman, Eve: created by a personal God, Yahweh. Hence this personal God is known by His personal name. We may now put these two parts of the equation together:

The situation presented here differs from the Mesopotamian polytheistic scheme in which the god(s) who created man and the personal god of the individual generally were different members of the pantheon. In Genesis 1 and 2 the great Creator God and the personal God of Adam and Eve were one and the same, as is indicated by the connection between these two narratives, both by content and by the divine names used in them.

We might also note in conclusion that when man's face-to-face fellowship with his Creator began at his creation the name Yahweh Elohim first appears in the Genesis record (chapter 2) and when this face-to-face fellowship finally ended with man's fall (chapter 3) the compound name of Yahweh Elohim disappears for the rest of the biblical record. In other words, this particular form of the divine name was used for that particular period in man's history when the persons of the first man and woman held open converse with their personal God and Creator; and when that relationship was broken, the particular formulation for the divine name disappears from the record.

In summary, there is a distinct "name" theology involved in the distribution of the different names used for God in Genesis 1 and 2. The author who composed these two narratives as parts of a larger whole, as discussed above, wished to say something specific about God by using these names in this way. Just as something more is said about man and his creation in Genesis 2, so also something more is said about God in this narrative not only about what He did, but also about His personal relationship with His creation. Thus the process of naming recorded in Genesis 1 and 2, and its significance, applies not only to the objects created, but also to God Himself.

IV. EPILOGUE

As the writing of this study was drawing to a close, there came to my attention Jerome T. Walsh's article, "Genesis 2:4b-3:24: A Synchronic Approach" [24], in which he points out a number of features that Genesis 2 and 3 share in common, thus indicating that they were composed as an entire unit, as we have suggested above for Genesis1 and 2. Assuming that Walsh's view of the unity of Genesis 2 and 3 is correct, and assuming that the analysis presented above on the composition of Genesis 1 and 2 as a unit is also correct, then the composition of Genesis 1-3 as an entire unit should be attributed to one author on one occasion or very close to that point in time.

FOOTNOTES

[1]E.A. Speiser, 1964, Genesis, Anchor Bible, vol. 1, Doubleday, Garden City, New York, pp. 18-19. I have utilized Speiser's translation freely in the quotations from Genesis that follow below.

[2]See, for example, U. Cassuto, 1961, A commentary on the book of Genesis, vol. 1, trans. I. Abrahms, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, p. 17.

[3]For a discussion of this point see W.F. Albright, 1968, Yahweh and the gods of Canaan, Doubleday, Garden City, New York, pp. 42-52.

[4]For formulaic language in some of the earliest writing of mankind see B. Alster, 1975, Studies in Sumerian proverbs, Akademisk Forlag, Copenhagen, pp. 17-31. Just why the Israelite author of Genesis 1 should have had to wait until the exile, according to literary critical theory, to write in this fashion is unclear.

[5]This type of analysis of Hebrew poetry was developed especially by G.B. Gray (1915) in his major work on this subject, The forms of Hebrew poetry, Hoddern and Stoughton, London.

[6]This type of analysis of Hebrew poetry goes all the way back to Bishop Lowth's landmark study on this subject published in 1753, De Sacra Poesi Hebraeorum, and it is still followed by scholars working in this field today.

[7]Analyzing Hebrew poetry by counting syllables has been proposed recently by D.N. Freedman, and an introduction to his thought on this approach can be found in the prolegomenon to the reprint of G.B. Gray's (1972) The forms of Hebrew poetry, KTAV, New York.

[8]J.B. Pritchard, ed., 1955, Ancient Near Eastern texts relating to the Old Testament, Princeton University Press, p. 228.

[9]Ibid., pp. 374-375.

[10]Ibid., pp. 376-378.

[11]Ibid., pp. 405-407.

[12]Ibid., pp. 407-410.

[13]Ibid., pp. 375-376.

[14]Ibid., pp. 34-36.

[15]Ibid., pp. 421-424.

[16]Ibid., pp. 164-180.

[17]On this point see G.E. Mendenhall, 1970, Ancient oriental and biblical law, The Biblical Archaeologist Reader, vol. 3, Doubleday, Garden City, New York, pp. 10-12.

[18]Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern texts, pp. 331-342.

[19]Speiser, Genesis, p. XXII.

[20]Ibid., p. 19.

[21]G.F. Hasel, 1975, The meaning of "let us" in Genesis 1:26, Andrews University Seminary Studies 13:65-66.

[22]Speiser, Genesis, p. 15.

[23]Ibid.