©Copyright 2018 GEOSCIENCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE

11060 Campus Street • Loma Linda, California 92350 • 909-558-4548

SIMILAR PLAN, SIMILAR RESPONSE: THE BIBLICAL NARRATION OF PLANETARY BEGINNINGS AT CREATION AND AFTER THE FLOOD

by

Ronny Nalin

Geoscience Research Institute

ABSTRACT

Genesis narrates God’s instructions to humans and their response to these instructions after two planetary beginnings: creation (Gen 1: 28-3:21) and the flood (Gen 9:1-27). Strong linguistic and semantic parallelisms between the accounts highlight the consistency of some principles God considers essential for the structure of His creation and our dealing with it, both before and after the entrance of sin. The reiterated concepts include abundance, expansion, hierarchy in the creation, fullness within boundaries, the special value of humans, and the universality of the covenant. Similarly, parallels in the two accounts illustrate the trajectory humans follow in departing from God’s initial plan and His consistent response to our shortcomings.

The understanding of God’s vision for the creation and our role in it, which emerges from comparing the two accounts, can contribute to the framing of the foundations of a biblically-informed approach to environmental issues.

INTRODUCTION

Parallelism is a rhetorical figure of great relevance in biblical literature. Besides adding elegance and musicality to a written text, parallelism enhances communicative functionality by establishing an internal structure, reinforcing ideas of central importance, and allowing for expression of multiple meanings inherent to a single concept. This literary technique is considered a hallmark of biblical Hebrew poetic compositions.[1] A conceptually comparable phenomenon, however, can be discerned at a larger scale in the structure of some narrative segments of the Hebrew Bible. Several studies, for example, have illustrated how the book of Genesis contains entire sections arranged in a symmetrical or parallel pattern, allowing the tracing of correspondences between different portions of the text.[2]

This article examines linguistic and thematic parallelisms found in two passages of Genesis (Gen 1:28-3:21 and Gen 9:1-27)[3] that describe God’s instructions to humans at creation and after the flood, and their subsequent response. Creation and the flood are the two planetary events when God’s direct action in nature sets the stage for a beginning in the history of humanity.[4] Therefore, comparison of the two accounts helps us: a) identify some principles of God’s vision for creation and our role in it; b) investigate the impact of sin on God’s original vision; c) understand the consequences of non-compliance with God’s plan, and d) highlight God’s consistent response to our shortcomings. Aspects reiterated in the two narrations can provide a biblical background for a theological discussion of guiding principles of stewardship of the creation.

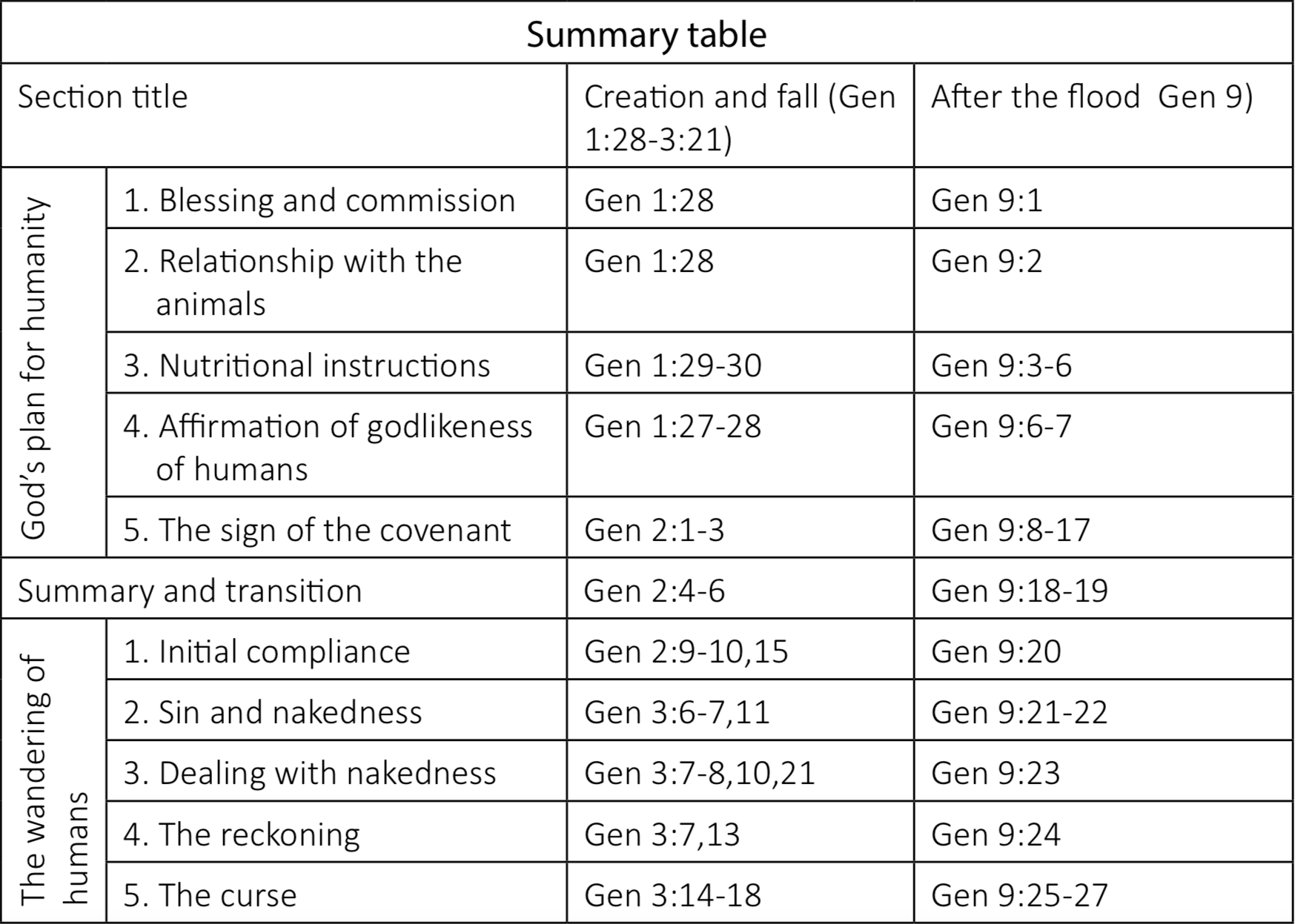

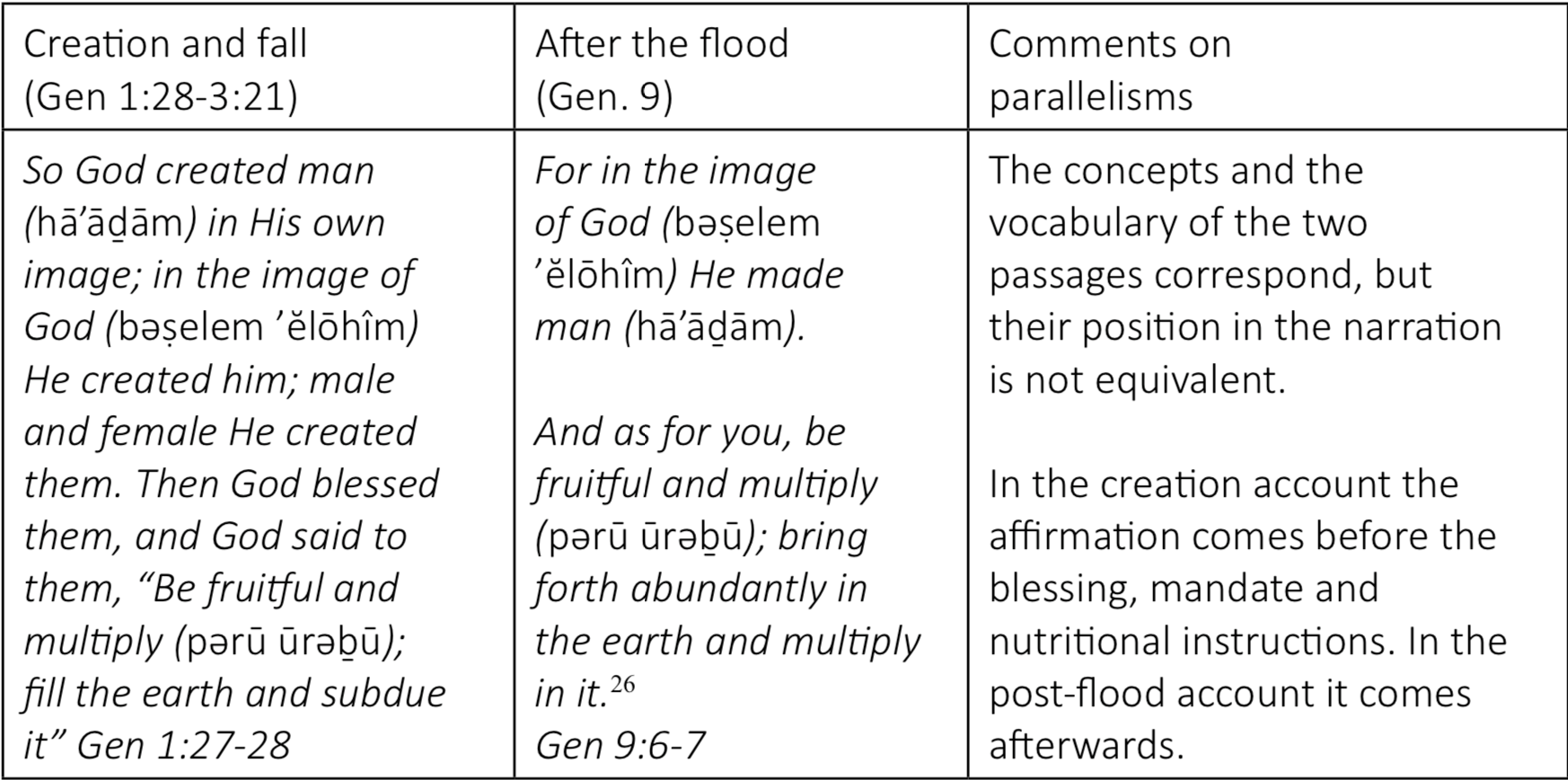

The general structure and the sequence of parallel sections are summarized in the following table[5]:

The various sections are discussed in the remainder of the paper, following the sequence shown in the table.

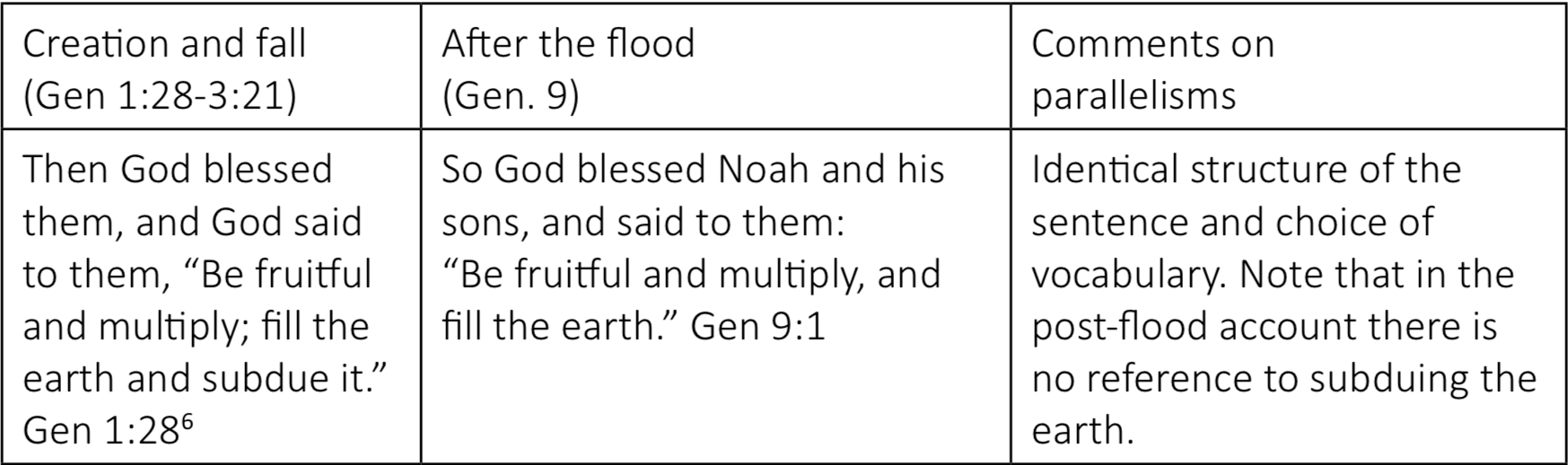

God's plan for humanity: Blessing and commission

The essence of God’s plan for humanity is the same before and after the fall. His positive outlook, signified by the blessing imparted on Adam and Eve and Noah and his sons, foresees a life of expansion, fulfillment, and abundance. These concepts are implied by the use of terms like “be fruitful and multiply” (pərū ūrəḇū).[7] They also illustrate that God endowed His creation with a potential for growth and expansion. The idea of an immutable and static creation is foreign to the narration of God’s original plan. The Creator wants to lead humanity along a dynamic path of growth and discovery.

In the creation account, the mandate of filling the earth is intimately connected with subduing it, because the expansion entails interaction with new unexplored areas.[8] The process of subduing the earth depicts an active and intentional role of humans in working for the accomplishment of God’s vision.[9] Interestingly, the verbal pair “fill the earth and subdue it” (ūmil’ū ’eṯ-hā’āreṣ wəḵiḇšuhā) is broken in the post-flood account, where reference to subduing the earth is omitted.[10] This difference already signifies a changed, more antagonistic interaction with the environment after the entrance of sin, as more explicitly indicated in the following section about the relationship with other creatures.[11]

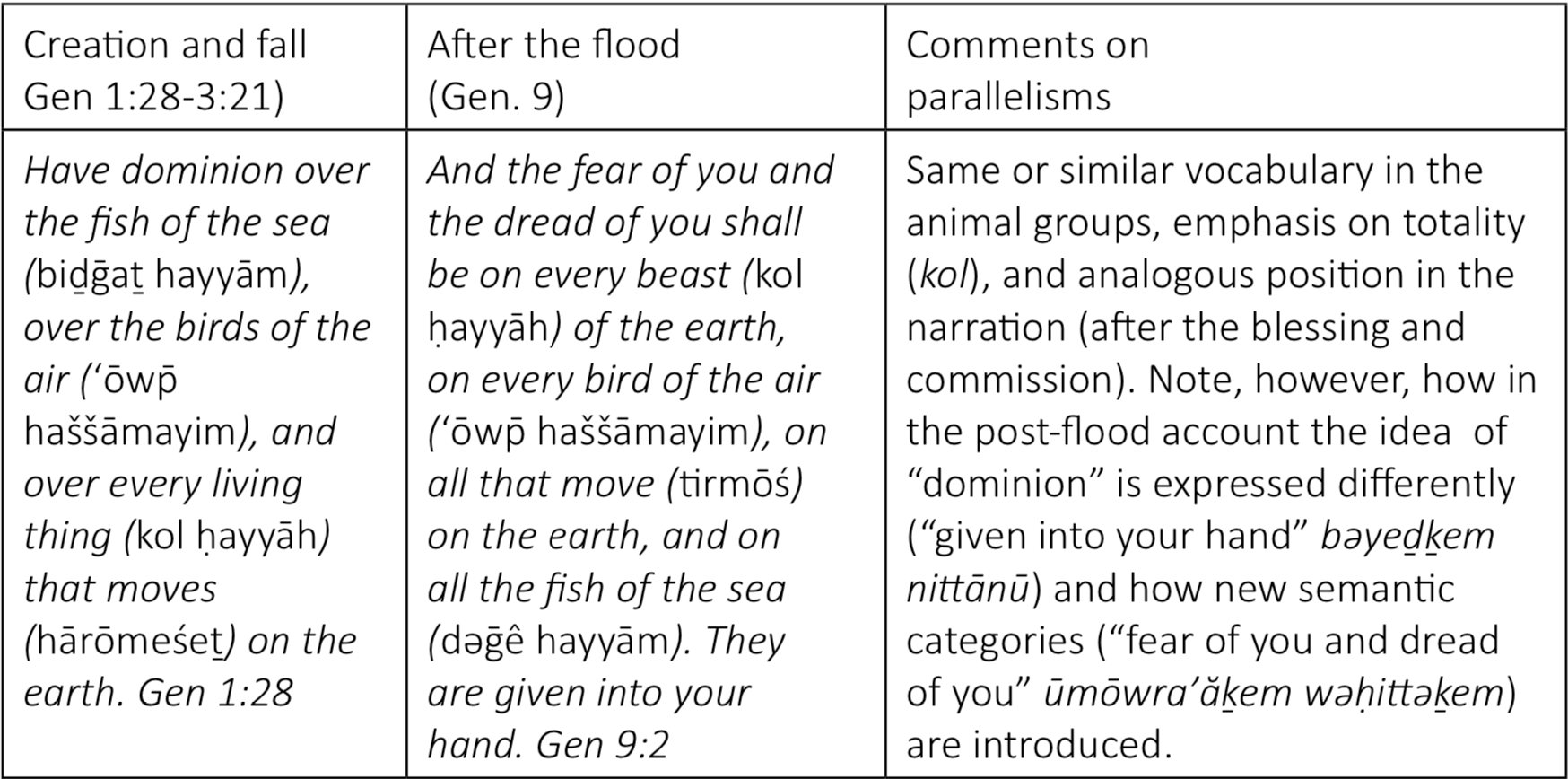

God’s plan for humanity: Relationship with other created living beings

God’s creation has an internal hierarchic structure which is reaffirmed after the flood. Humans are given dominion over and are placed on a higher level than all other living creatures on the earth. Both passages exclude plants from the enumeration of living beings under human dominion. This is because, although from a modern perspective plants are certainly considered living organisms, the Hebrew view of the time was different. Life was seen as related to the presence of blood or breathing (e.g., Gen 1:30, Gen 9:4, 10, Lev 17:14, Deut 12:22) and the terms life and death are not used in direct reference to plants in the OT.[12] The divine pronouncement of human dominion is specified towards the animals, because the verb rāḏāh is a term that includes a relational component that can only be established with other living beings.[13] Several scholars have rightly pointed out that this “dominion” is modeled after God’s rulership of creation and entails caring responsibility rather than tyrannical exploitation.[14]

Unfortunately, the effects of sin cannot be completely removed at the fresh start after the flood. Fear and dread are negative connotations that were not present in the creation account.[15] We must conclude that sin impacted the ecology of created beings so deeply that even a new beginning had to be framed within the rules of a sinful system.[16]

Comparison of the passages leaves the impression that while to have dominion in the post-creation conditions was a proactive enterprise, submission of other creatures in the post-flood world is a passive result of fear and they are helplessly delivered into the hand of rather than positively engaged by humans.[17]

It is noteworthy that neither of the two verbs uttered by God in Genesis 1 to instruct humans on their relationship with the earth and its other inhabitants – kāḇaš (to subdue) and rāḏāh (to rule) – is repeated in the Genesis 9 account. These verbs portray well the original, hopeful divine vision giving humans an active role of strong leadership in the discovery, management, and development of the natural world. However, the omission of these words in Genesis 9 can hardly be interpreted as coincidental and is instead likely to reflect God’s awareness of the limits introduced by sin to the human ability of exerting responsible stewardship towards the creation.[18]

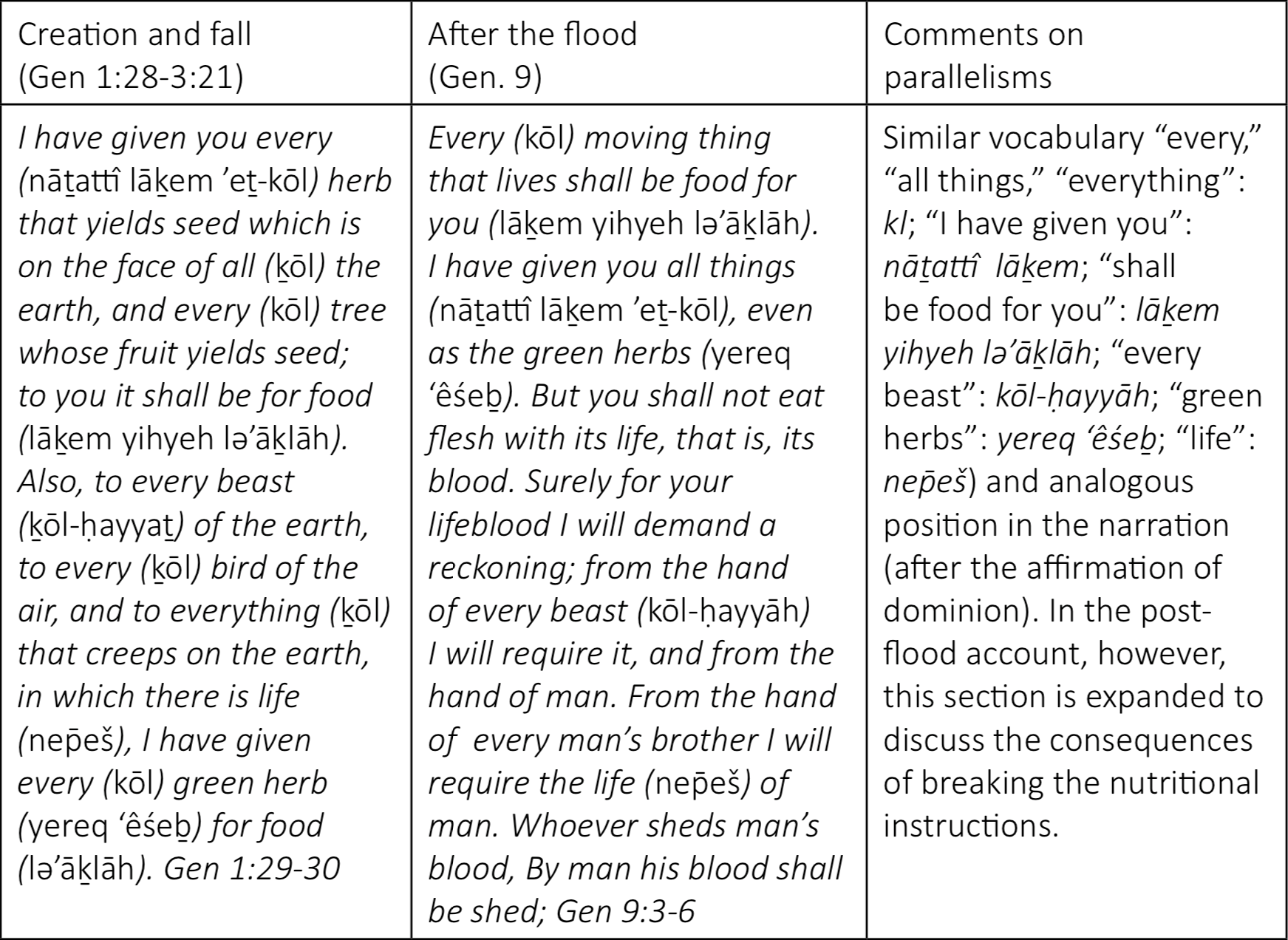

God’s plan for humanity: Nutritional instructions

The next step in God’s disclosure of His plan is the proclamation of nutritional rules for created beings. By stating what living creatures are to eat, God is also affirming the distinction between Creator and creature. He is the one who decides what is assigned to us for our most basic need. Food is essential for life, and we cannot self-determine how to sustain ourselves, because we are creatures. The nutritional prescriptions can be seen as an indirect way of setting boundaries within the universe of man.[19] However, these rules are given,[20] and anything that is given is a gift, not a subtraction. By providing boundaries, God is adding to and not taking away from our experience. Moreover, the choice of words (kol: “every”, “all things”, “everything”) indicates that He is not restrained but gives with totality. The actual items given for food change between the creation and the post-flood accounts, but what remains unvaried is that all things within the allowed categories are made available.[21]

It is interesting to note that the proclamation of nutritional rules comes immediately after the affirmation of human dominion. This almost appears as God’s way of protecting humans from the delirium of omnipotence and the risk of forgetting the distinction between God and creature. Moreover, by directly following the affirmation of dominion, the rules act as qualifiers of the way humans are to exert their authority, protecting the value of the life of other living beings.[22]

When comparing nutritional instructions given at creation with those given after the flood, it again becomes evident that the reality of sin impacted the original plan. For example, the entrance of death in the world implies that living creatures can kill and eat each other. However, the post-flood account shows God’s ability to preserve His vision even when interacting with a corrupted system. After creation, living creatures were not supposed to eat things with life in them.[23] The same principle is reaffirmed after the flood through the prohibition of eating “flesh with its life, that is, its blood” (Gen 9:4).

Nutritional instructions and the affirmation of human dominion in the creation account indicate that creation was designed as stratified, with the following hierarchical organization: first layer: plants; second layer: living creatures of the sea, air, and land; third layer: humans.[24] Even though the fall changed the interactions between these layers, God is able to reaffirm and maintain the same hierarchical structure in the post-flood nutritional instructions. Before the fall, levels 3 (humans) and 2 (other living creatures) could feed on level 1 (plants). After the fall, level 2 can feed on 1, and level 3 can feed on 2 and 1. The possibility of level 2 (animals) feeding on level 3 (humans) and level 3 “feeding” on 3 (man killing his fellow man) is strongly condemned as an aberrant transgression of the basic scheme.[25]

God’s plan for humanity: Affirmation of godlikeness of humans

Being made in the image of God is the rationale for humans to be placed at the highest level of God’s creation.[27] In the creation account, the godlikeness of humans is stated both as part of God’s initial design (Gen 1:26) and at its implementation (Gen 1:28). It therefore precedes and is constitutive of any relational interaction of humans with their Creator and the rest of the creation. However, in the post-flood account the godlikeness of humans is mentioned at the end of the nutritional instructions section, as a justification to the prohibition of shedding blood. Sadly, the advent of sin and violence signifies a loss of appreciation for the image of God in us, so much so that God’s original vision needs to be reaffirmed.[28]

In the post-flood account, the divine commission for humans is repeated at this point, in contrast to the creation account, where it is uttered only once. In the threatening conditions of a sinful world, God desires to reassure and encourage a weak and fragile man facing the unknowns of a new beginning. The mandate to be fruitful is reaffirmed in opposition to the concept of blood shedding and life taking of the preceding verses, as if God was saying: “Do not worry, this is not my plan. My plan for you is one of life and expansion, not of killing and death”.[29]

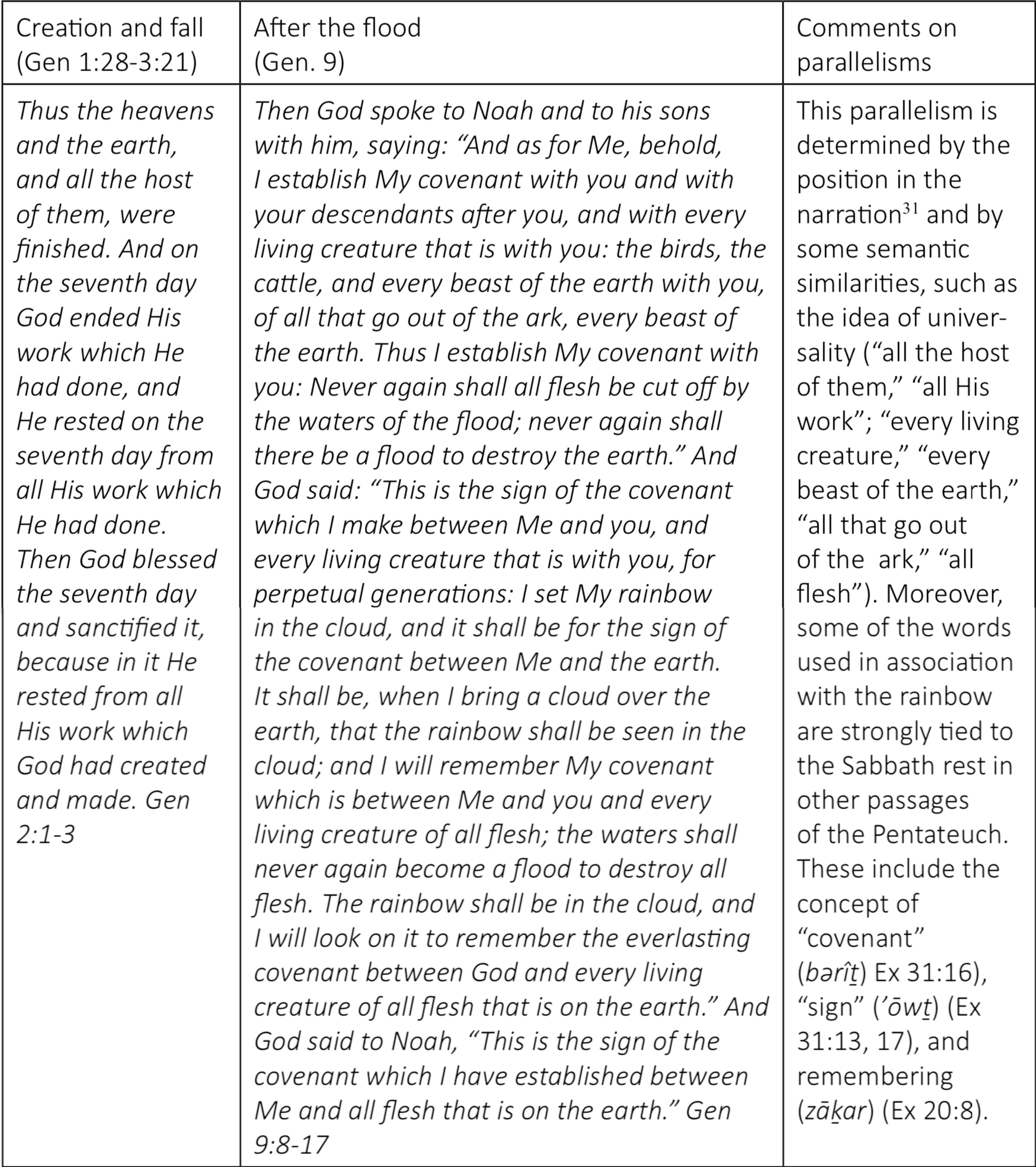

God’s plan for humanity: The sign of the covenant and its universality [30]

After completing His address to humans and before letting them go to accomplish the plan set forth for them, God takes the unilateral initiative of establishing a sign commemorative of His mighty interaction with His creation.

Both the Sabbath and the rainbow are “remembrance signs.” The events of divine intervention to which the signs point are so unique in time and nature that a memorial that can occur repeatedly over the lifespan of a person needs to be established, otherwise the perception of their authenticity would be lost. The “remembrance” aspect of the signs also implies the true significance of God’s interaction with His creation can be assimilated only through continual reflection.

In the case of the Sabbath rest, humans are the ones invited to remember (Ex 20:8), whereas in the case of the rainbow it is God who promises to remember (Gen 9:16). One is a sign which commemorates creation (Gen 2:3; Ex 20:11), the other incorporates an indirect reference to destruction (Gen 9:15). The reality of sin, therefore, is again accented with a darker shade in the post-flood account.

Finally, the passages make it clear that the value of these signs extends to the whole creation and their significance is not restricted to humans but, starting from them, encompasses “all His work which God had created and made.” In this respect, God’s covenant is universal and the role of humans within creation is seen as the central component of a larger interconnected system.[32] The flood impacted the whole creation. Therefore, the covenant signified by the rainbow is also stipulated with “every living creature that is with you.” Noah the ambassador, surrounded by the animals, is the interlocutor appointed by God for an elevated dialogical relationship with the Creator. In this role resides the great responsibility of representation and accountability for a vibrant world of life which God cares for immensely.[33]

Summary of starting conditions and transition to the next narrative section

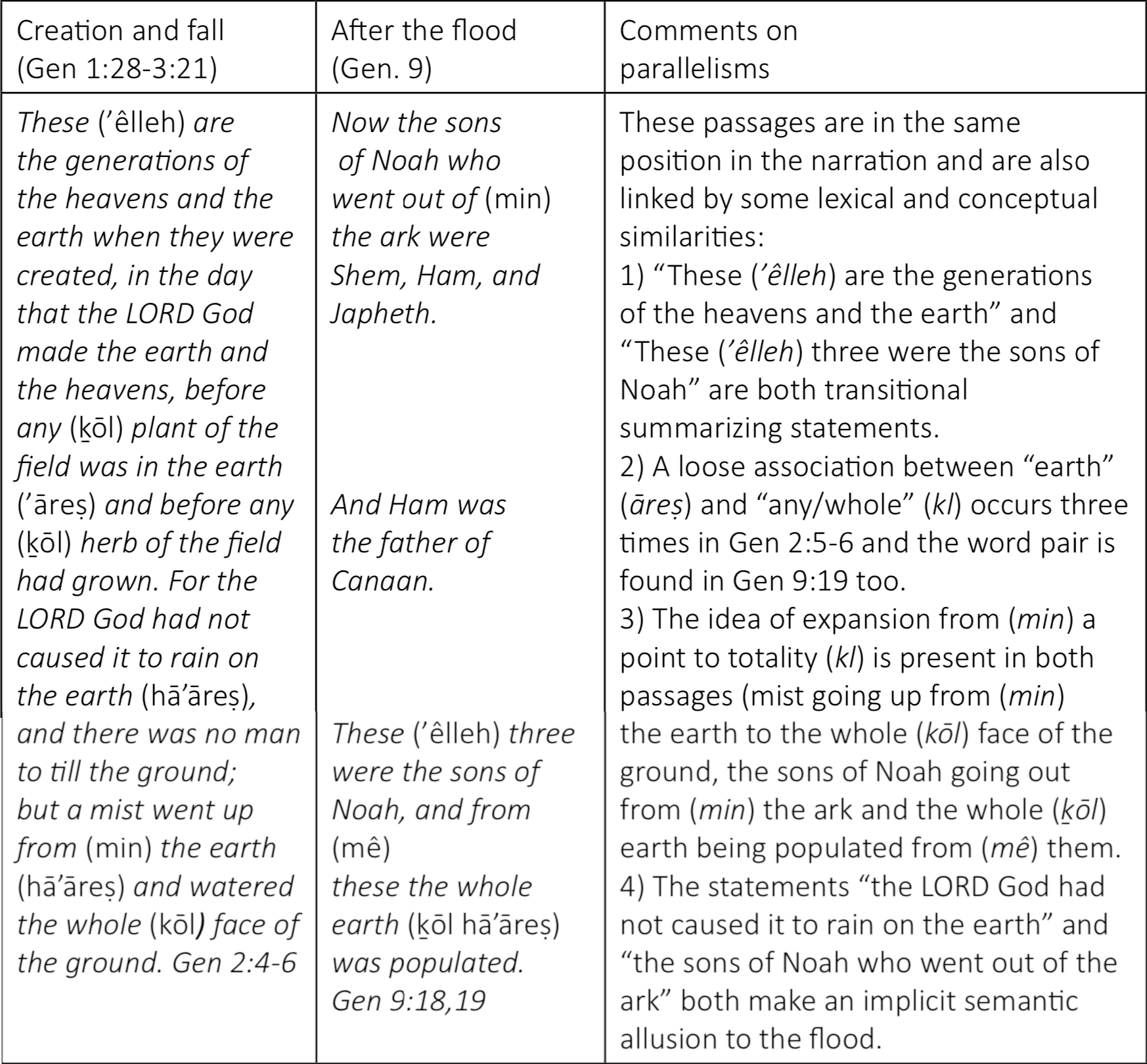

This section accomplishes in both accounts the same textual function of closing the preceding narrative unit (God’s establishment of the starting conditions) and bridging to the next unit (the response of humans to God’s plan).

After offering a summarizing statement (“These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created”; “These three were the sons of Noah” “who went out of the ark”), there is an important outlook which is adopted in both of these transitional parallel passages: the “not yet” (ṭerem) perspective.[34] In the creation account we are informed of how the plants and herbs of the field had not grown yet, God had not caused it to rain on the earth yet, and there was no man to till the ground yet. In the post-flood account clear mention is made that Ham was the father of Canaan, who, at the time of the exit from the ark, was not born (Gen 10:1) and had not become a people yet.[35] This information is offered from the perspective of the writer who knows already the future unfolding of the events. Note how these allusions are conceptually connected to the entrance of sin and its effects,[36] and therefore cast a darker overtone to the narration.

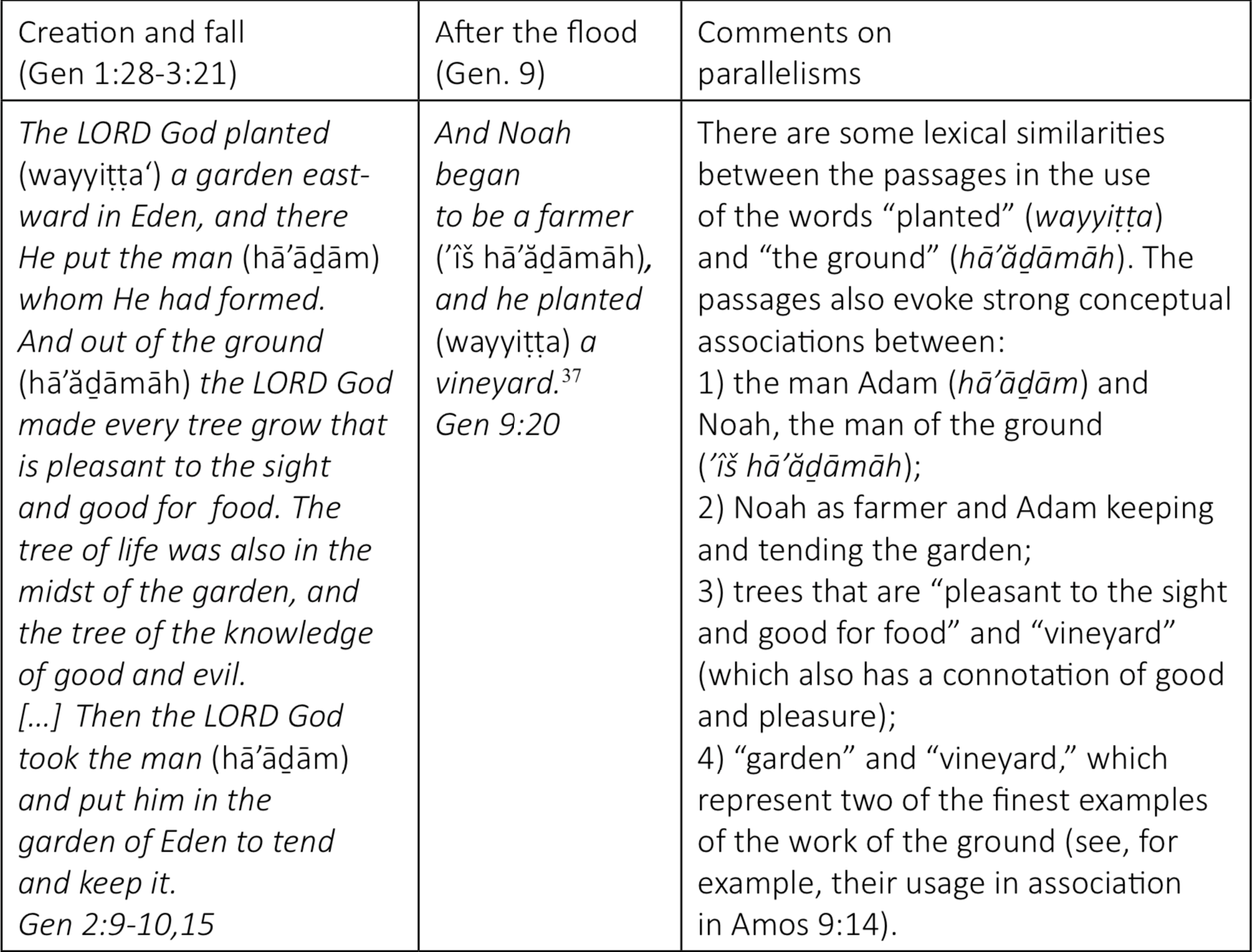

The wandering of humans: Initial compliance

A clear shift from the universal to the particular can be noticed in both accounts, as the new narrative section is entered[38]. After the proclamation of the principles that are to govern the whole creation, God begins with Adam and with Noah the first of innumerable journeys He takes with each individual human being. But the narrower context of the action (the garden of Eden and Noah’s vineyard) does not constrict the scope of God’s vision. On the contrary, God’s universal mandates find their effective application in the microcosm of every person living on the earth.

God placed Adam in Eden, so that he could learn to take care of the very trees which produced the fruit his life was dependent upon for sustainment. When Noah, in the post-flood beginning, resumes the agricultural enterprise, the continuity of God’s project is affirmed. God’s vision for humanity implies active participation in the circle of interdependence that links living creatures to their environment. This vision remains unchanged even in a sinful world and provides a balanced perspective to the complexion of human dominion on creation. However, the use of the word “began” (wayyāḥel) implies that something new is happening. Noah is not just resuming God’s plan, but beginning in a new context.[39]

Numerous were the trees from which Adam and Eve could select fruit for nutrition. However, the presence of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the midst of the garden introduced an element of choice in their decision to follow God’s instructions. In Gen 9, the stylistic structure of the pericope starting with Noah’s decision to plant a vineyard suggests a strong connection between this initial action and the unfortunate events which follow.[40] There is an echo, in the planting of this vineyard, of the potential for good or bad developments that existed in the Garden of Eden, even if Noah had not been aware of the multiple uses and effects of the fruit of the vine.[41]

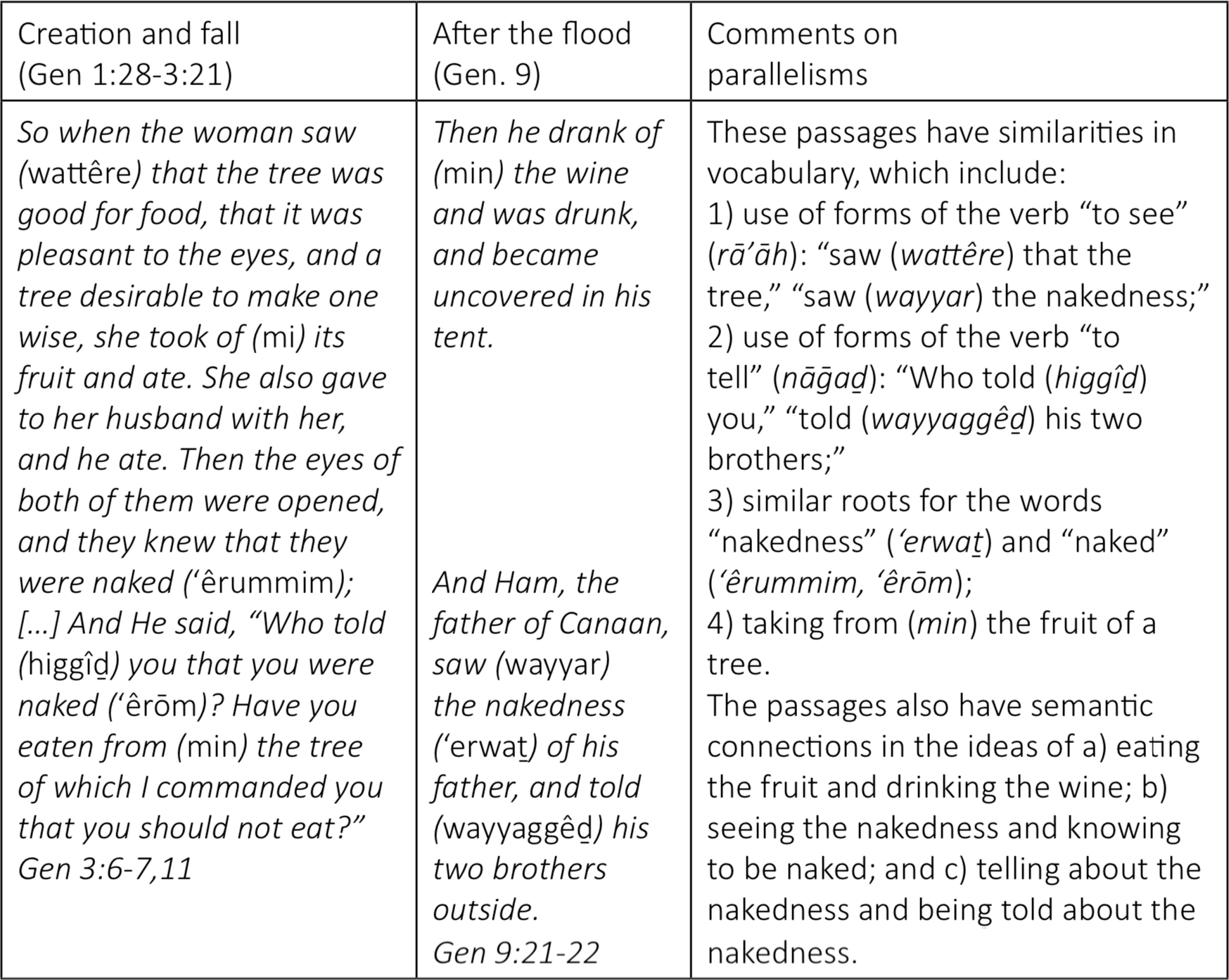

The wandering of humans: Sin and nakedness

Both stories expose the dramatic connection between sin and nakedness. Our wrong choices leave us vulnerable, uncovered, in fear of the fragility of our condition. Note that in both accounts it is not the condition of nakedness in itself which is negative but rather the realization (the seeing) of nakedness. Likewise, the disclosure of this nakedness (“Who told you?”) signifies acknowledgment of a new state of being that cannot be hidden or denied. In the original creation, there was no threat in openness and vulnerability because the absence of sin excluded the exploitation of this condition. After the fall, Adam becomes afraid, being naked represents a weakness, and its exposure an occasion of sin. By not being afraid of publicly (“outside” – baḥūṣ – as opposed to “inside” – bəṯōwḵ – Noah’s tent) sharing the news about his father’s nakedness, Ham demonstrates his endorsement of this sinful predatory and opportunistic outlook in life. Ham’s disclosure to his brothers of his sinful experience also epitomizes the common pattern of trying, once fallen, to drag others into the swamp of iniquity, which has its parallel in Eve’s sharing of the fruit with her husband.

In both accounts, it is the action of eating or drinking from the fruit of a tree that leads to the condition of nakedness. As seen in the section on nutritional instructions, food is a symbol of our dependence on the Creator. Sin, therefore, is the decision to satisfy our basic needs by following our inclinations instead of God’s directions. This egoistic perspective is represented also by the action of seeing (the qualities of the fruit or the nakedness of the father), which is a factor reported in both stories. It is not a passive, casual, and accidental seeing that we are told about in the accounts but an action which is already a choice, a way of thinking, planning, and evaluating. This look comes from eyes that already see the world in a way that is not consistent with God’s view. Namely, it is a look which sees the resources and the people that surround us from a self-centered perspective.[42]

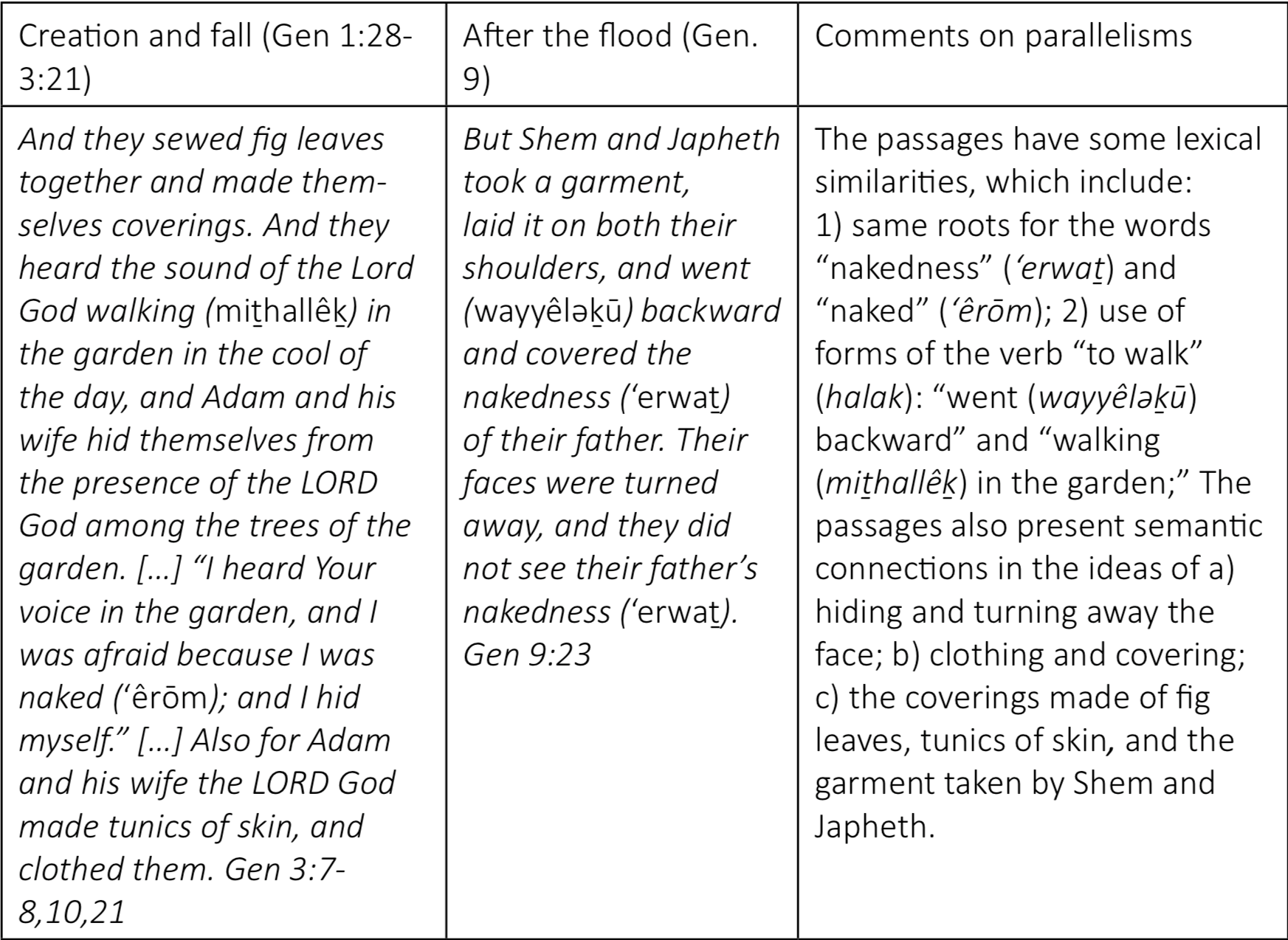

The wandering of humans: Dealings with nakedness

The commonest reaction after sin is to try to cover up. The nakedness of fallen humanity generates fear and an impulse to find a solution through the fabrication of a presentable image.

At this stage in the narration we have powerful similarities and important differences in the two passages, describing the nature of the somehow uncomfortable encounter necessary to begin the process of restoration. In both accounts, the spatial fulcrum of the scene is the most intimate place (the garden and the tent). The place where sin is generated must also be the place where it is addressed. In both accounts we witness a scene where motion is a central element. In the garden, God walks in search of the human couple while they avoid His presence. This Edenic hide-and-seek portrays God as the active seeker, conveying the message of intentionality and care of Our Maker who steps into our broken world. In the post-flood account, the motion is also towards the place of nakedness, but the actors are now humans, not God. This change in the context of a fallen world is emblematic of an important decision all are called to make. Two possible paths are presented to every human, the movement of Ham (revealing nakedness out of the tent) or the movement of Shem and Japheth (covering nakedness back in the tent). What is depicted in the backward movement of the brothers is almost a rewinding, an undoing of what Ham has done. The same fear of being seen naked, first experienced by Adam and Eve, is acknowledged and respected by Shem and Japheth through their avoidance of looking at the nakedness of their father (the new Adam). Their choice is to fix their gaze away from nakedness, the opposite of Ham’s impropriety. Furthermore, there is a restorative purpose to their action. Instead of simply looking away, they move towards their father and lay a garment over him in a way that is intimately aware of his vulnerability. In this gentle gesture we find the same warmth, vicinity, and centripetal motion displayed by God in His visit to Adam and Eve in the garden. We should also highlight that there is a sense of community portrayed in this effort. Shem and Japheth work together and the garment they hold lays on the shoulders of both[43] of them. This is a wonderful model of the posture we should adopt in attempting to bring healing into a fallen world.

It is interesting to see that all the possibilities for covering nakedness are presented in the two episodes: we can do it by ourselves (Adam and Eve), someone else can do it for us (sons of Noah), or we can be covered by God. Note, however, that God’s tunics do not simply cover (kāsāh) but clothe (lāḇaš) us. They are tailored to restore our dignity much more effectively than coverings of fig leaves.

The vocabulary of this passage resonates strongly with the imagery of the sanctuary related to sin and atonement,[44] hinting at the provision which God will make for restoring His creation.

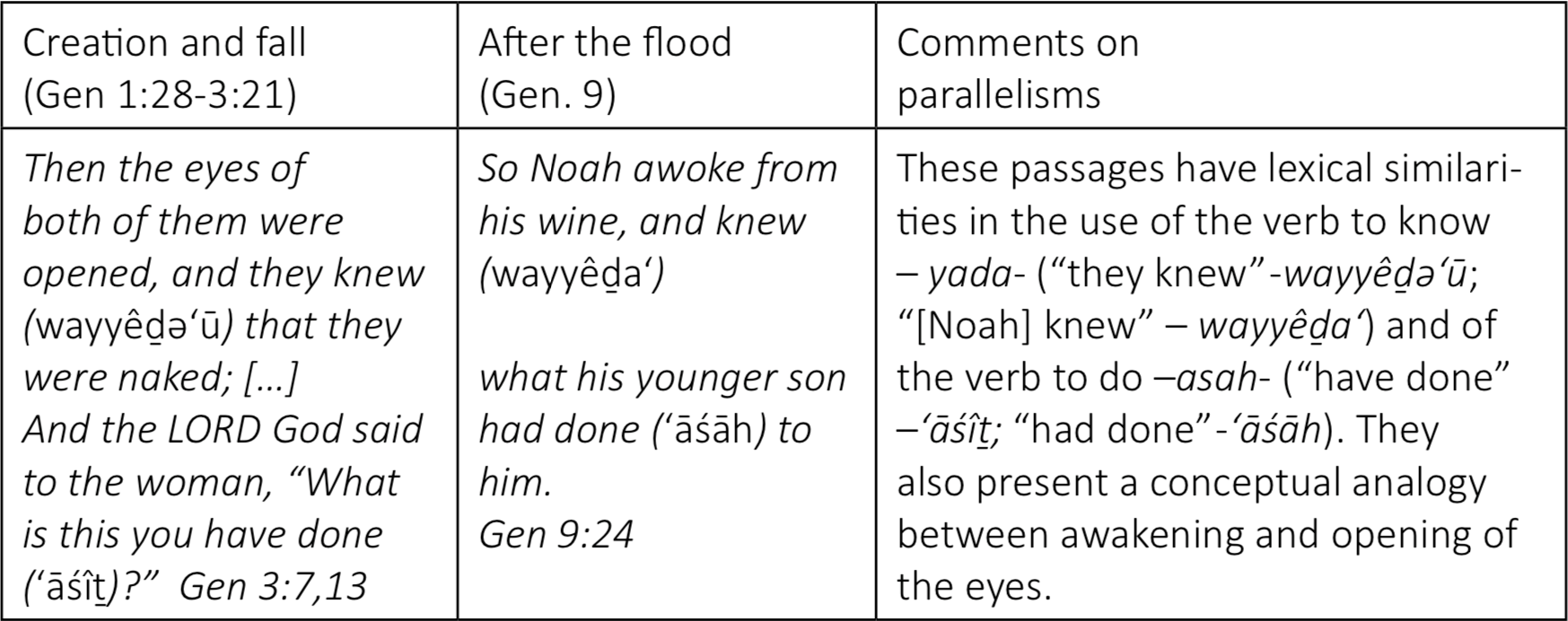

The wandering of humans: The reckoning

As much as we try to pretend we are covered, with sin there is always a moment of reckoning.[45] In both narrations awareness is expressed by the usage of the verb yāḏaʿ (to know), which implies a more than cursory acknowledgment of the situation. The experience of this new dispensation of things is likened to an awakening after inebriation, but unfortunately the new reality dissolves any excitement that may have been brought by the eating or drinking of the fruit.

Note how in both accounts there is an emphasis on what has been done. Sin is generated in the mind but finds expression in deeds that bring tangible consequences.

The reckoning of sin includes accountability for the actions performed. God directly addresses the protagonists of the fall, and Noah speaks out to his sons. Rather than being the expression of a harsh God or father, the confrontation brings a greater message of hope for the fallen creation. In requesting an account for the actions of humans, God is providing reassurance that justice will not be overthrown, and the laws which sustain the universe will not be disregarded without consequence. The Sovereign is implicitly affirming His continual supremacy, which is good news for the whole creation and an anticipation of the final restoration.[46]

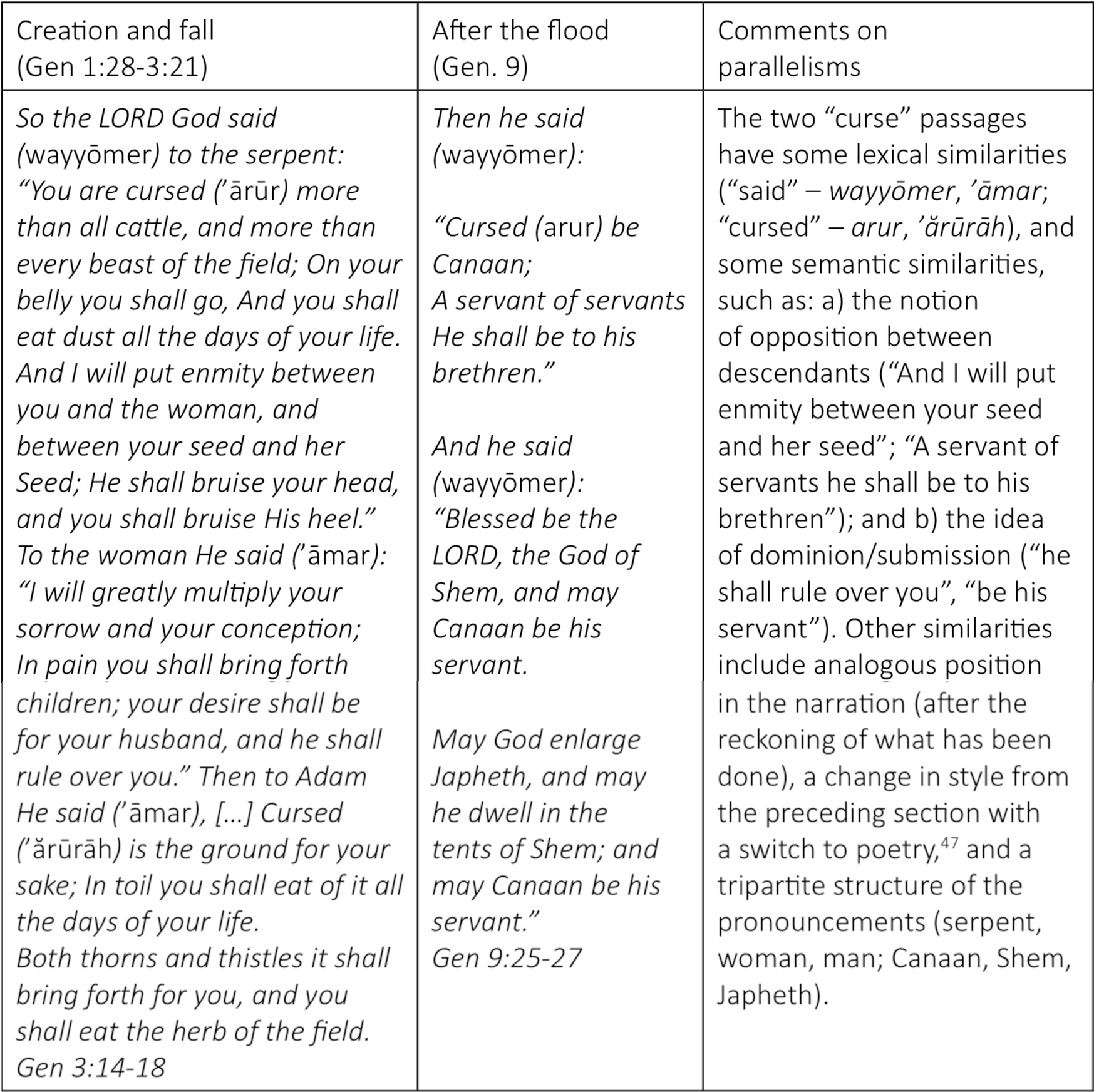

The wandering of humans: The curse

The curse section in the account of the fall is more extensive and encompasses all three layers of creation: the plants (“thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you”), the animals (“you are cursed more than all cattle, and more than every beast of the field”), and humans (“your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you”).[48] On the other hand, Noah’s pronouncements are focused only on the human dimension and the relational dynamics among his descendants. However, the language adopted in these passages accentuates the concepts of submission (“servant of servants,” “rule over you”),[49] struggle (“enmity,” “toil,” “thorns and thistles”), and suffering (“eat dust,” “bruise,” “sorrow,” “pain,”). Therefore, sin not only impacted the hierarchic levels of creation in themselves but also caused the interaction among them to become more authoritarian, aggressive, and hostile.

The most intriguing analogy in both accounts is that the curse introduces an element of conflict and enmity between the progenies of the characters of the story: in one case the seed of the serpent toward the seed of the woman, in the other the seed of Ham (Canaan) toward the seed of Shem (whose God is the Lord, and from which the Messianic line descends) and Japheth.[50] The servant relationship of Canaan to his brothers is remarked three times, and the expression “cursed be Canaan” is contrasted by “blessed be the Lord” in a dual oppositional scheme already established with the enmity between the serpent and the seed of the woman. Remarkably, both passages assert the role God plays in this dichotomous path: it is God who puts enmity, it is God who is to be blessed, not Shem.[51] This divine origination of an element of tension transforms the curse into a blessing. God is hinting at the fact that, in spite of our rebellion, He is taking action.[52] Paradoxically, we find comfort and hope for the future in the very proclamation of God’s judgment upon sin, no matter how impacted we have been by its effects.

CONCLUSIONS

1) This study has explored linguistic and thematic parallels contained in the Genesis narration of human beginnings at creation and after the flood. The striking connections between the two passages (also reflected in the general structure of the two accounts; see summary table) cannot be considered coincidental but reveal an intentional design on the part of the writer. These textual links provide another example of the internal unity and richness of resonances which characterize the book of Genesis.[53]

2) When comparing God’s instructions at the planetary beginnings of Genesis 1 and Genesis 9, the major lesson conveyed is one of affirmation, through repetition, of the continuity of God’s vision for humanity and its interaction with creation, even in a fallen world. The principles presented as enduring include a call to abundance and expansion, the existence of hierarchy in the creation, the setting of rules to regulate the dominion of humans, the provision of fullness within boundaries, the affirmation of the special value of humans, and a proclamation of the universality of God’s covenant with the creation.

3) The fall and post-flood accounts, however, do acknowledge the effects of sin in altering the original balance of creation, specifically through the introduction of death, killing, fear, dread, self-centeredness, exploitation of weakness, conflict, and suffering. In particular, the language in Gen 9:1-7 appears more neutral and cautious with respect to the active role of humans in exerting dominion over the creation, in light of the consequences of sin.

4) God’s ability to uphold His original vision while adjusting to the new conditions is an example of how principles of environmental stewardship should be rooted in the “very good” creation but recognize that we live in a fallen world. Awareness of the present corrupted state of things will bring into sharper focus the choice now faced by each human being, epitomized by the opposite moral trajectories of Ham and his brothers Seth and Japheth. As we seek to grow and expand in this world, we can choose an outlook of care, respect and compassion towards the rest of the creation or adopt a predatory attitude of exploitation and indifference. Perhaps, now more than ever it is our responsibility to “serve and guard” (Gen 2:15) the good that is still present on this earth.

5) From a theological perspective, the striking similarities between the post-creation and post-flood accounts could be seen as discouraging, in that they reveal how easily and consistently humans repeat the same mistakes and follow a pattern of disobedience to God’s plan. However, the real message portrayed by the parallelisms in the two accounts is quite the opposite, a message of assurance. God’s consistent course of intervention in history reveals the unwavering will and resolute design of a loving God, who does not let His vision for His creation fall in spite of our shortcomings. The testimony of the past projects to the re-creation of the future, sustaining the hope and certainty of another new beginning when God will definitively overcome the failures of human history.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M. Gutiérrez (Istituto di Cultura Biblica Villa Aurora) and especially J. Doukhan (Andrews University) are gratefully acknowledged for valuable discussion and comments on the parallels examined in this paper. N. Vyhmeister (Andrews University, Emer.) and R. Davidson (Andrews University) provided constructive reviews of an early and late version of the manuscript, respectively.

ENDNOTES

[1]For a good and concise discussion of the function of parallelism in biblical Hebrew poetry see A. Berlin, “Parallelism,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 5, ed. D. N. Freedman, (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992), p 155-62.

[2]Examples include structural parallels between Genesis 1 and 2, Genesis 1 and 3, Genesis 2 and 3, the accounts of creation and the flood, and within the account of the flood. See, for example, (a) J. B. Doukhan, 1978, The Genesis Creation Story: Its Literary Structure (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press); (b) W. H. Shea, 1978, “The Unity of the Creation Account,” Origins 16(2):9-38; (c) Shea, 1979, “The Structure of the Genesis Flood Narrative and Its Implications,” Origins 6(2):8-29; (d) W. Gage, 1984, The Gospel of Genesis: Studies in Protology and Eschatology (Winona Lake, IN: Carpenter Books); (e) Doukhan, 1987, Daniel: The Vision of the End (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press), p 134; (f) Shea, 1989, “Literary Structural Parallels Between Genesis 1 and 2,” Origins 16(2):4968; (g) Z. Stefanovic, 1994, “The Great Reversal: Thematic Links Between Genesis 2 and 3,” Andrews University Seminary Studies 32:47-56, hereafter referred to as AUSS; (h) R. M. Davidson, 2000, “A Biblical Theology of Creation,” in Christ in the Classroom: Adventist Approaches to the Integration of Faith and Learning, comp. H. M. Rasi, (Silver Spring, MD: Institute for Christian Teaching, Education Department, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists), 26-A:433-442; (i) R. Ouro, 2002, “Linguistic and Thematic Parallels Between Genesis 1 and Genesis 3,” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society 13(1):44-54, hereafter referred to as JATS; (j) Ouro, 2002, “The Garden of Eden Account: The Chiastic Structure of Genesis 2-3,” AUSS 40(2):219-243. Incidentally, all these authors propose that discovery of these textual connections strengthens the view of a single authorship for the book of Genesis.

[3]For other works specifically discussing parallelisms between these two sections see (a) Gage (Endnote 2d); (b) P. R. Davies, 1986, “Sons of Cain,” in A Word in Season: Essays in Honour of W. McKane, ed. J. D. Martin & P. R. Davies (Sheffield, UK: JSOT Press), p 38-39; (c) J. Blenkinsopp, The Pentateuch: An Introduction to The First Five Books of The Bible (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992), 57-58, 86-87; (d) C. M. Gutiérrez, 1993, L’Homme Créé à L’Image de Dieu dans L’Ensemble Littéraire et Canonique de Genèse, Chapitres 1-11 (Strasbourg: unpublished doctoral thesis), p vi + 347; (e) J. H. Sailhamer, 2008, “Genesis” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, revised edition, vol. I, Genesis-Leviticus, ed. T. Longman III & D. E. Garland (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan), p 133-135.

[4]According to 2 Peter 3:5-7, a third analogous planetary beginning will occur after the day of judgment. This beginning is obviously outside the scope of this study.

[5]The sequence of sections in the table has been identified following the narrative order in the account of Genesis 9, and listing the parallel passages from Genesis 1 to 3. The starting point for the comparison in this study consists of the divine blessing and commission present in both narrations, although parallels have also been identified in previous sections of the creation and flood accounts (see Endnote 2).

[6]Quotations are from the NKJV.

[7]In the post-flood account the blessing is directed to “Noah and his sons”. The association of Noah with his progeny is in itself an allusion to the concepts of fertility and expansion emphasized in the mandate.

[8]The link between expanding and subduing is reinforced by the parallel structure of the passage, where “be fruitful” (pərū) (A) corresponds to “fill the earth” (mil’ū ’eṯ-hā’āreṣ) (A’) and “multiply” (rəḇū) (B) corresponds to “subdue” (ḵiḇšu) the earth (B’).

[9]The semantic range of the verb “subdue” (kāḇaš) in the Hebrew Scriptures has been suggested to include a connotation of forcefulness in the face of resistance and construed to imply the existence of a hostile and ferocious environment in the original creation outside the Garden of Eden (cf. R. E. Osborn, 2014, Death Before the Fall [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press], p 28-33). However, the following textual considerations caution against the reading of subdue in Gen 1:28 as intended to convey the notion of a “violent struggle:” 1) The immediate context indicates that the verb is in parallel with the concept of expansion and multiplication of descendants (see Endnote 8). Therefore, kāḇaš expresses a sense of ultimate completion, the accomplishment of God’s mandate of filling the earth; 2) This reading is strengthened by the use of kāḇaš in Joshua 18:1, an allusion to the creation account of Gen 1. God had ordered humans to subdue the earth, and now Israel has fulfilled this vision: at the end of the long journey out of Egypt, the land has indeed been subdued; 3) The only other passage where kāḇaš is used in the Pentateuch (Num 32:22,29) also revolves around the idea of completion. Moses fears that the children of Reuben and the children of Gad will abandon the other tribes before the land God has given to Israel is brought into full possession; 4) Instead of emphasizing violence, these land-related passages focus on the actual achievement of control over a divinely pre-ordained space. At the creation, much of the earth was still uninhabited, and only through growth and expansion could Adam and Eve effectively accomplish the goal of subduing this space; 5) There is one instance (1 Chr 22:18) where the subduing of the land under the kingdom of David is placed in direct parallel with the subjugation of its inhabitants. However, even in this passage the main point David is making is that a condition of rest has been accomplished by completely subduing the land. There is no more work to do, the land is subdued, the time is ripe for Solomon to build a sanctuary; 6) There are several texts where kāḇaš is used of slaves instead of referring to the land (2 Chr 28:10; Neh 5:5; Jer 34:11). This other usage seems to highlight a semantic connotation of subordination and ownership over someone rather than violence. Only a later use of the verb (Esth 7:8) narrows its meaning into the forceful physical subjugation of an individual. 7) An implication of vigor and force can very well be present in the semantic range of kāḇaš without necessarily implying violence or resistance, and instead indicating domination accomplished through deliberate effort. As commented by F. Delitzsch (1987), “The authorization and vocation to dominion over the earth employs such strong expressions as שבכ [subdue] and הדר [have dominion], because this dominion requires the energy of strength and the art of wisdom.” (A New Commentary on Genesis [Edinburgh: T&T Clark], p 101); 8) As discussed in the main text, the mandate to subdue the earth is not repeated in the parallel passage, after the flood. It is evident that what kāḇaš represented in a pre-fall world became somehow more difficult to attain in a world tainted by the entrance of sin. Based on all these considerations, we should not interpret the expression subdue the earth as an injunction to launch into a terrible battle against the hostile elements. Rather, it is a call to bring to completion a firm and stable capillary control, by a fully mature and expanded human population, of a physical environment designed and formed by God. In similar fashion, W. D. Reyburn & E. McG. Fry (1997) note about this text: “TEV translates ‘bring it [the earth] under control’; SPCL says ‘Fill the earth and govern it.’ Subdue and have dominion over are parallel expression with reference to the plants and animals that God has put on the earth. This is not a command to go to war, but for their first people and their offspring to ‘take control, be in charge, have direction over.’” A Handbook on Genesis (New York, NY: United Bible Societies), p 52.

[10]In the post-flood account, the mandate is repeated again in Gen 9:7 and some translators include the phrase “and subdue it” in that formulation. Endnote 26 discusses this aspect in more detail.

[11]Gage (Endnote 2d, p 27) notes very poignantly how the two parts of the commission (filling the earth and subduing it) are directly impacted by the curse after sin, whereby “Man’s labor of subduing the earth becomes wearisome, and woman’s labor of filling the earth becomes sorrowful.” C. J. Collins (2006) also comments on the irony of how the verb multiply of Gen 1:28 is used in Gen 3:16 in reference to the multiplication of pain, in the very process (childbearing) which makes the mandate of multiplication possible (Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary [Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing], p 153, 169).

[12]Doukhan, 2015, “When Death Was Not Yet: The Testimony of Biblical Creation,” in The Genesis Creation Account and Its Reverberations in the Old Testament, ed. G. A. Klingbeil, [Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press] p 339.

[13]C. Westermann (1994) observes: “Why is there mention of the animals only? Are not humans to exercise dominion over the rest of the creation as well? In the thinking and language of P and of the Old Testament dominion can be exercised only over what is a living being. The relationship to plant life is different as vv. 29-30 show; a relationship to metals or chemical substances could not be called ‘dominion.’” (Genesis 1-11: A Continental Commentary [Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press ], p 159). Two more considerations can be offered against the suggestion that these passages are indicating that human dominion does not extend beyond the animal world: 1) In Gen 1:26, the list of what humans should have dominion over includes also a generic “and over all the earth” (ūḇəḵōl hā’āreṣ). C. F. Keil (2006) comments: “There is something striking in the introduction of the expression “and over all the earth,” after the different races of animals have been mentioned, especially as the list of races appears to be proceeded with afterwards. [...] God determined to give to the man about to be created in His likeness the supremacy, not only over the animal world, but over the earth itself;” (Commentary on The Old Testament, Volume 1: The Pentateuch [Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers], p 39-40). However, some scholars consider the reading of the Masoretic Text faulty, due to a scribal omission of the word תיח (ḥayyaṯ), which is present in the Syriach Version, before “the earth,” and translate this passage “over all the wild animals,” in parallel with the expression “beasts of the earth” of Gen 1:24,25 (e.g., Westermann, p 79; R. Alter, 1996, Genesis [New York, NY: Norton & Company], p 5). U. Cassuto (1998) disagrees on the need to postulate a corruption of the Masoretic Text, and suggests we are instead looking at an intentional stylistic variant meant to avoid the monotony of repetition in the list of animals. Therefore, dominion “over all the earth” should still be understood in the context of animal diversity, as a “generic expression that includes also that which is not specifically named. In our verse we have the phrase, and over all the earth, which implies both the creeping things and the beasts.” (A Commentary on The Book of Genesis: Part I, from Adam to Noah [Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University], p 57); 2) Even if the verb rāḏāh (to have dominion over) in Gen 1:26 (and Gen 1:28) was only meant to be applied to the animals, Gen 1:28 contains a broader mandate to subdue the earth. The verb kāḇaš (to subdue) does imply control (see Endnote 9). Therefore, governance over the earth certainly includes mastery over terrestrial plants, which are intimately connected with the earth, as demonstrated by their creation on the third day, after the appearance of dry land.

[14]The verb rāḏāh (to rule) has been invoked to legitimize human violence over the animals, including their killing (see, for example, the following quote by D. Snoke (2006): “The command to ‘subdue’ and ‘rule over’ the animals may plausibly be taken to mean ‘have power to kill.’” A Biblical Case for an Old Earth [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books], p 67). However, Doukhan remarks that “In Genesis 1:26,28, the verb rādâ, ‘to have dominion,’ which is used to express humankind’s relationship to animals, is a term that belongs to the language of the suzerain-vassal covenant and of royal dominion without any connotation of abuse or cruelty.” (see Endnote 12, p 333). Davidson adds that “It is clear that no cruelty is implied in this term, because when one is said to have dominion with cruelty, the term ‘with cruelty’ is added (Lev, 25:43, 46, 53).” (“The Genesis Account of Origins,” in The Genesis Creation Account; full reference in Endnote 12), p 123. For further theological discussions of the “dominion” concept, see (a) J. Moltmann, 1985, God in Creation: A New Theology of Creation and The Spirit of God (New York, NY: Harper & Row), p 29-30, 224-225; (b) M. Welker, 1999, Creation and Reality (Minnneapolis, MN: Fortress Press), p 60-73; (c) M. G. Brett, 2000, “Earthing the Human in Genesis 1-3,” in The Earth Story in Genesis, ed. N. C. Habel & S. Wurst (Cleveland, OH: The Pilgrim Press), p 73-86.

[15]J. Olley (2000) presents an insightful discussion of how the post-flood account of Genesis 9, including the covenant section, is greatly concerned with the impact of sin on the whole creation (“Mixed Blessings for Animals: The Contrasts of Genesis 9,” in The Earth Story, p 130-139; full reference in Endnote 14c).

[16]For an exegetical discussion on how Genesis contrasts the conditions before and after sin, see Doukhan, p 329-342 (Endnote 12).

[17]Furthermore, Doukhan suggests that in its biblical usage the expression “given into one’s hands” often carries a connotation of force and aggression (p 338, Endnote 12).

[18]Blenkinsopp (2011) makes similar considerations when analyzing the new dispensation portrayed in Gen 9:1-6: “In a certain sense this new mandate can be seen as a kind of normalization, a realistic acceptance of life in a world which has lost its innocence. There remains nevertheless a deep and sad sense that this is not the way it was meant to be. The new order is by no means a complete restoration. [...] it seems as if the deity has come to terms with the limitations of human moral capacity. This is now a damaged world calling for damage control.”(Creation, Un-Creation, Re-Creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1-11, [New York, NY: T&T Clark International],p 145-146).

[19]G. von Rad comes to a similar conclusion: “This Word of God, therefore, means a significant limitation in the human right of dominion.” Genesis: A Commentary, The Old Testament Library (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1961), p 59.

[20]Perhaps, a similar association between the concepts of giving and boundaries is hinted at in Gen. 1:17, where the verb nāṯan “to give” is used for the first time in Genesis. There, the luminaries are set (given) to govern day and night and separate light from darkness.

[21]This attitude of giving abundantly resonates with the words of Jesus: “That they might have life, and that they might have it more abundantly” (John 10:10).

[22]Cassuto, for example, excludes that dominion over the animals implied the right to kill them for nutrition, based on his reading of Gen 1:29-30: “You are permitted to make use of the living creatures and their service, you are allowed to exercise power over them so that they may promote your subsistence; but you may not treat the life-force within them contemptuously and slay them in order to eat their flesh; your proper diet shall be vegetable food. It is true that eating of flesh is not specifically forbidden here, but the prohibition is clearly to be inferred” (p 58, Endnote 13).

[23]On plants not being considered as having life in them, see previous discussion in the “relationship with other created living beings” section.

[24]Identification of a hierarchical arrangement in the creation should not justify the trivialization of the intrinsic value of each of its component. Plants, for example, are certainly included in the divine commission to “serve and guard” the Garden of Eden (Gen 2:15) and several passages in the OT imply care for the land, trees, and their management (e.g., Ex 23:10-11; Lev 25:2-7; Deut 20:19). Perhaps most importantly, God Himself designed for the higher levels of the creation to be dependent upon the lower ones for nutrition (Gen 1:29-30). As the source of human sustainment, plants are an integral part of a divinely ordained link of interdependence. For theological reflections on the value God places on all aspects of His creation, see (a) J. A. Davidson, 2013, “How Does God Regard His Creation?” in Entrusted: Christians and Environmental Care, eds. S. Dunbar, L. J. Gibson, and H. M. Rasi, (Mexico: Adventus), p 3-12; (b) A. R. Schafer, 2013, “How Can Environmental Care Be Grounded in Biblical Theology?” in Entrusted, p 25-34.

[25]No specific mention is made of the possibility of level 2 feeding on 2 (animals eating other animals). Whereas at creation God specifies the diet of animals, after the flood animals are addressed only with reference to the shedding of human blood. The focus here is on affirming the value of human life in the context of a fallen world. God will demand a reckoning only for the life of humans, because they are the only ones made in the image of God (Gen 9:6b). This silence on blood shedding between animals can be read as God’s implicit acceptance without active endorsement of this pattern of nutrition in the new dispensation.

[26]Some scholars (e.g., Westermann, p 469 [Endnote 13]; Alter, p 39 [Endnote 13]) substitute the final “and multiply in it” (ūrəḇū-ḇāh) of Gen 9:7 with “and subdue it” (ūrəḏū-ḇāh), arguing for a transposition in the Masoretic Text from ūrəḏū (“and subdue”) to ūrəḇū (“and multiply”). This approach would result in a closer correspondence with the Gen 1:28 version of the mandate and eliminate the repetition of “and multiply” (ūrəḇū) in Gen 9:7. However, commentators do not agree on the matter (see, for example, the convincing counter-argumentation of Cassuto, 1997, A Commentary on The Book of Genesis: Part II, from Noah to Abraham [Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University], p 128-129). Moreover, it should be noted that even with the “and subdue it” (ūrəḏū-ḇāh) reading there would not be complete correspondence between the mandate in Gen 1:28 and that in Gen 9:7 because a different verb is used for the expressions “fill the earth” (mil’ū ’eṯ-hā’āreṣ) and “bring forth abundantly in the earth” (širṣū ḇā’āreṣ).

[27]Many commentators have emphasized how the godlikeness of humans and their dominion over nature are related. See, for example, von Rad, p 57-58 (Endnote 19); Welker, p 60-73 (Endnote 14b); Collins, p 61-67 (Endnote 11); Davidson, 2015, “The Nature of the Human Being from the Beginning: Genesis 1-11” in “What Are Humans Beings That You Remember Them?” Proceedings of the Third International Bible Conference, Nof Ginosar and Jerusalem, June 11-21, 2012, ed. C. Wahlen (Silver Spring, MD: Biblical Research Institute), p 11-21.

[28]See von Rad: “Even though a profound disorder has occurred in the world with the incursion of the violent struggle for existence, nevertheless God does not retreat from it, nor withdraw his demands on it; God does not abandon his sovereign claim over all creatures. He watches over all life in the world,” p 129 (Endnote 19).

[29]The waw of contrast before “you” in Gen 9:7 (“And as for you”, wə’attem), intends to create antithesis with the concepts expressed in the antecedent passage. Furthermore, the emphasis on fertility and abundance (as opposed to death and killing) is accentuated by the choice of the word širṣū “bring forth abundantly,” which is the same verb (sometimes translated as “teem” or “swarm”) used for the creation of marine creatures in the fifth day (Gen 1:20-21), and by the repetition of the verb ūrəḇū “and multiply.”

[30]Beginning with this section, one could argue for a change in the nature of the parallels between the two accounts. Whereas there is an almost one-to-one correspondence between Gen 1:2830 and Gen 9:1-7, the connections between the rest of the two accounts are less direct, with some unequally expanded or non-comparable sections. However, the structural arrangement of Gen 9 continues to follow the pattern of the narration in Gen 2-3, including some lexical and stylistic similarities (see comments on parallelisms in the tables and endnotes), making the parallels evident enough not to be overlooked.

[31]Doukhan (Endnote 2e, p 134) presents a parallelism between the seven days of creation in Gen 1-2 and the account of the aftermath of the flood in Gen 8-9. In this scheme, the seventh day Sabbath of Gen 2:1-3 corresponds to the covenant section of Gen 9:8-17.

[32]On the topic of God’s post-flood covenant and its ecological implications for the relationship between humans and other living beings, see Olley, p 136-139 (Endnote 15).

[33]The universality of the covenant also reinforces the bond between humans and other living creatures, their fellow covenant beneficiaries. We find a sense of intimacy and even partnership in the fact that both humans and animals are addressed with the same term (nep̄ eš ḥayyāh) in both the creation and post-flood accounts (Gen 1:20,21,24,30; 2:7,19; 9:10,12,15-16).

[34]For a more extended treatment of the not yet concept in Genesis 2-3, see (a) Doukhan, p 336 (Endnote 12); (b) Doukhan, 2004, “The Genesis Creation Story: Text, Issues, and Truth,” Origins 55:23.

[35]Placing this reference to Canaan in the parallel scheme of the not yet condition eliminates some of the apparent complexity in the interpretation of this passage, which has led some commentators to see the reference to Canaan as an insertion by a later redaction (e.g., von Rad, p 131-132 [Endnote 19]; Westermann, p 486 [Endnote 13]).

[36]The “herb of the field” (‘êśeḇ haśśāḏeh) and “Canaan” are even mentioned in the respective curses (Gen 3:18; 9:25-27), “to till the ground” (la‘ăḇōḏ ’eṯ-hā’ăḏāmāh) is used in Gen 3:23 in the context of the expulsion form Eden, and the verb to rain (māṭar) is used next after Gen 2:5 in Gen 7:4, in reference to the flood. For a more detailed analysis of some of these connections, see R. W. Younker, 2000, “Genesis 2: A Second Creation Account?”in Creation, Catastrophe, and Calvary ed. J. T. Baldwin (Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald), p 69-78.

[37]The translation of this passage is debated. Several authors prefer to connect the verb “began” (wayyāḥel) with “planting a vineyard” (wayyiṭṭa kārem), essentially making the text affirm that Noah’s was the discoverer of viticulture or the first to plant a vine (von Rad, p 132-133 [Endnote 19]; Westermann, p 487 [Endnote 13]; Alter, p 40 [Endnote 13]; Cassuto, p 158161 [Endnote 26], Reyburn & Fry, p 217 [Endnote 9]). Keil, p 108 (Endnote 13), translates the verse with a more neutral “And Noah the husbandman began, and planted a vineyard,” but seems nevertheless to imply that Noah was the first to cultivate the vine.

[38]See, for example, Cassuto, p 108-109 (Endnote 13), discussing the planting of the trees in the garden of Eden as opposed to the creation of vegetation on day 3 of Gen 1.

[39]This idea is expressed in the original text also by the phrase ’îš hā’ăḏāmāh (“to be a farmer” or “husbandman”) referring to Noah. It is difficult to render the richness of allusions contained in this expression, which could be translated as “the man of the ground.” First of all, the word ’ăḏāmāh creates a connection with Adam, whose corresponding role Noah holds in the postflood account. Secondly, this ’ăḏāmāh is not just the original ground that had been cursed (Gen 3:17), but is also a new setting for the old plan to take place. On the interconnections revolving around the concept of ’ăḏāmāh in the first 9 chapters of Genesis, see Gutiérrez, p 229-230 (Endnote 3d).

[40]The section describing the actions of Noah (Gen 9:20-21) consists of a close succession of verbs conceptually related in a sequential way, with minimal intervening specifications. The resulting effect for the reader is of a high-paced process, something of a chain reaction, well rendered in the KJV: “And Noah began to be an husbandman, and he planted a vineyard: And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent.” The spiritual implication of this stylistic arrangement is that sin happens through a fast and interconnected series of steps (see James 1:14-15). Interestingly, the parallel passage describing the fall in Gen 3:6-7 conveys a similar impression of high-paced progression: “She took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband with her; and he did eat. And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons.” (KJV). On the brevity and celerity of the description in Gen 3:6, see Cassuto, p 147-148 (Endnote 13).

[41]On this, commentators do not agree, especially in light of alternative translations of Gen 9:20 concerning Noah as the first to plant a vineyard (see Endnote 39). Among those who accept the “first to plant a vineyard” translation, some do not consider Noah accountable for his drunkenness (e.g., von Rad: “[Noah] is completely overpowered by the unsuspected power of this fruit. The reader, therefore, must on no account morally condemn this drunkenness,” p 133), whereas others still consider the episode a fall (e.g., Keil, p 98 [Endnote 13]). The stylistic structuring of the text (Endnote 40) seems to suggest that the action of Noah was not neutral but initiated, and was therefore inextricably connected to, the process which led to Noah’s nakedness and Ham’s interaction with it.

[42]Note how the following verse in the post flood account (Gen 9:23) specifically mentions that Shem and Japheth (in opposition to Ham) “did not see their father’s nakedness.” The verb rā’āh (to see) in conjunction with nakedness is used again.

[43]The word for “both” (šənêhem) in Gen 9:23 is used only twice before this passage: the first in Gen 2:25, to describe the original condition of Adam and Eve, when “they were both naked” and there was no shame; the second in Gen 3:7, when “the eyes of both of them were opened” and they became aware of their nakedness. Therefore, this third passage is effectively linked in a trajectory related to the issue of nakedness: no shame in nakedness, followed by nakedness and fear, followed by covering the nakedness. The entrance of sin is a collective tragedy, but we can also share in the effort of mitigating its results.

[44]“The text employs technical terms that belong to sanctuary language, specifically to the clothing of the priests. The word ketonot “tunics” is often used of priestly garments (Exod 28:4, 39-40; 29:5, 8; 39:27; 40:14; Lev 8:7, 13; 10:5, 16:4; Ezra 2:69; Neh 7:70) and the causative form (hiphil) of the verb wayyalbishem “clothed” is used particularly to refer to the dressing of the priests (Exod 28:41; 29:8; 40:14; Lev 8:13).” Doukhan, 2016, Seventh-Day Adventist International Bible Commentary, Volume 1, Genesis, (Nampa, ID and Hagerstown, MD: Pacific Press & Review and Herald), p 110-111.

[45]Jesus’ remark comes to mind: “There is nothing covered that will not be revealed, and hidden that will not be known” (Matt 10:26).

[46]See Romans 8:19-22.

[47]On the poetic style of Gen 3:14-19, see Westermann, p 257 (Endnote 13). On the poetic

rhythm of Gen 9:25-27, see Cassuto, p 166, 168 (Endnote 26).

[48]In contrast, Collins, p 162-166 (Endnote 11), does not believe the text implies any physical change in the natural world but merely a change affecting humans and their nature.

[49]Keil, p 99-100 (Endnote 13), points out that even the name Canaan means “the submissive one”. The verb kāna‘ (“to subdue”) is associated to the name Canaan as a play on words in other parts of the OT (e.g., Judg 4:23; Neh 9:24).

[50]The wider scope of Noah’s pronouncements, encompassing the nations descending from Ham (Canaan) and his brothers rather than solely these three individuals, is argued well by Cassuto, p 154-155, 166 (Endnote 26) and acknowledged by other commentators (e.g., Keil, p 99-101 [Endnote 13]; Doukhan, p 165 [Endnote 44]).

[51]Doukhan notes: “While the curse stays at the human level, the blessing takes us to the divine level: Blessed be the Lord, the God of Shem (9:26). It is interesting that while humans are cursed, it is not Shem but only his God who is blessed. The idea is that any blessing derived from Shem originates, in fact, in God (12:3),” (Doukhan, p 165 [Endnote 44]).

[52]Some commentators criticize the reading of a “protoevangelium” in Gen 3:15 (e.g., von Rad, p 90 [Endnote 19]), while others are in favor of this interpretation (e.g., Collins, p 155-159; Doukhan, p 100-103 [Endnote 44]). Even without seeing a direct messianic reference in the passage, the text clearly shows God’s intervention (“I will put enmity”) in the context of the conflict between His people (the seed of the woman paralleled by Shem, whose God is the Lord) and the seed of the serpent (paralleled by Canaan).

[53]It would be legitimate to ask if these parallels are to be interpreted as the product of literary imagination or as reflecting actual events. I believe that, although the choice of lexicon and organization of the narration was the fruit of thoughtful reflection on the author’s side, the repeated pattern originates from a true historical succession of events. For a more expanded explanation of this hermeneutical approach to Genesis, see Doukhan, p 12-33 (Endnote 34b).