©Copyright 2018 GEOSCIENCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE

11060 Campus Street • Loma Linda, California 92350 • 909-558-4548

THE STRUCTURE OF THE GENESIS FLOOD NARRATIVE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS

by

William H. Shea

Associate Professor of Old Testament

Andrews University

WHAT THIS ARTICLE IS ABOUT

In a previous article (Origins5:9-38), Dr. Shea examined the literary structure and content of the first two chapters of Genesis to see if source critics were justified in claiming the existence of two antithetical accounts of creation. His analysis revealed ample support for a unified account of God’s creative acts as recorded by one author.

Applying these same principles of literary criticism to Genesis 6-9, scholars have dissected the flood narrative into small, discrete segments. According to their analyses, these units come from two different sources, J and P, and subsequently have been woven together in a complex pattern. With a multiple authorship, separated by centuries, it would be easy to conclude that the Genesis flood account contains duplications and contradictions and therefore does not necessarily provide a factual account of the sequence of events that took place in one major episode.

Dr. Shea begins this article by dividing the flood account into eleven sections, each representing one thought or sense unit. His rhetorical analysis of the overall literary structure reveals these units to be the building blocks of a detailed, organized narrative, suggesting a single author. Further evidence against a multiple authorship is found when the author examines some of the “proofs” used by source critics. The passages citing the numbers of animals taken into the ark are usually considered to be duplications and are attributed to different sources. Here, Dr. Shea shows that these so-called duplications actually provide evidence for parallelism, a literary technique employed by the ancient Semites in their poetry and prose.

Another argument for multiple sources is found in the chronological statements of the flood account. Source critics have attributed statements about time periods to J, while assigning the more precise chronological data of Noah’s life to P. The writer of this article believes them to be inconsistent in applying this methodology and offers a scheme for all the data in which the patterns for both the periodic and specific chronological data contribute to the literary structure of the narrative. This harmonious integration makes multiple authorship seem unlikely.

In the final section, Dr. Shea discusses certain chronological elements from four Mesopotamian flood stories. Though these stories are similar in literary construction to the flood account, no Assyriologist would see any reason for separating the stories into multiple sources. This shows a definite dichotomy in methodology between biblical and ancient Near Eastern studies, and Dr. Shea suggests that biblical literature should be evaluated in comparison with the literature of the ancient Semites who were contemporary with the biblical Hebrews.

PLEASE NOTE: Unfortunately, we are unable to reproduce all of the special accent marks that were present in our printed version of the Hebrew transliteration. Our apologies for any inconvenience this might cause.

In an earlier issue of Origins (5:9-38) I discussed the literary critical problem posed by the parallel recitations of God's creative acts in Genesis 1 and 2. The problem is relatively straightforward: either there are two creation stories from the J (Yahwist) and P (Priestly) sources, as literary critics would have it, or there is one creation account told in two parallel and related passages, as I concluded.

The analyses proposed for the flood narrative of Genesis 6-9 are of a different nature. Here, literary critics see many small and discrete textual units from the J and P sources that have been woven together in a rather complex pattern. In a relatively representative work, Speiser divided these three chapters into 24 units which range in size from portions of verses to a series of consecutive verses, alternating them between his J and P sources and assigning a dozen such units to each [1]. From his analysis of the sources, Speiser concluded that "we are now faced not only with certain duplications, but also with obvious internal contradictions, particularly in regard to the numbers of the various animals taken into the ark, and the timetable of the Flood" [2]. Since Speiser dated P some four centuries later than J, his supposed internal contradictions are only a natural outgrowth of his theory of the composition of this narrative.

By atomizing the text into miniscule segments, source critics have missed its overall structure, which actually represents a remarkably powerful and detailed organization of the literary vehicle in which the flood account was told. Detection of that structure also contradicts the thesis that the flood narrative represents a series of statements from two sources that were woven together. Furthermore, an overall structural analysis of Genesis 6-9 provides some interesting explanations for its various features, including the supposed contradictions mentioned above.

The basic work of analyzing the overall structure of the flood account was done by U. Cassuto [3], a conservative Jewish commentator. Considering the conclusions to which he came, it is not surprising that he rejected the standard documentary approach to this and other narratives in the Pentateuch. More recently, B. Anderson has presented a new study of the structure of the flood narrative [4]. It was this study which stimulated my thinking on this subject, and while I am indebted to him for the basic idea worked out below, I differ with both Cassuto and Anderson in working out some of the details in this analysis [5].

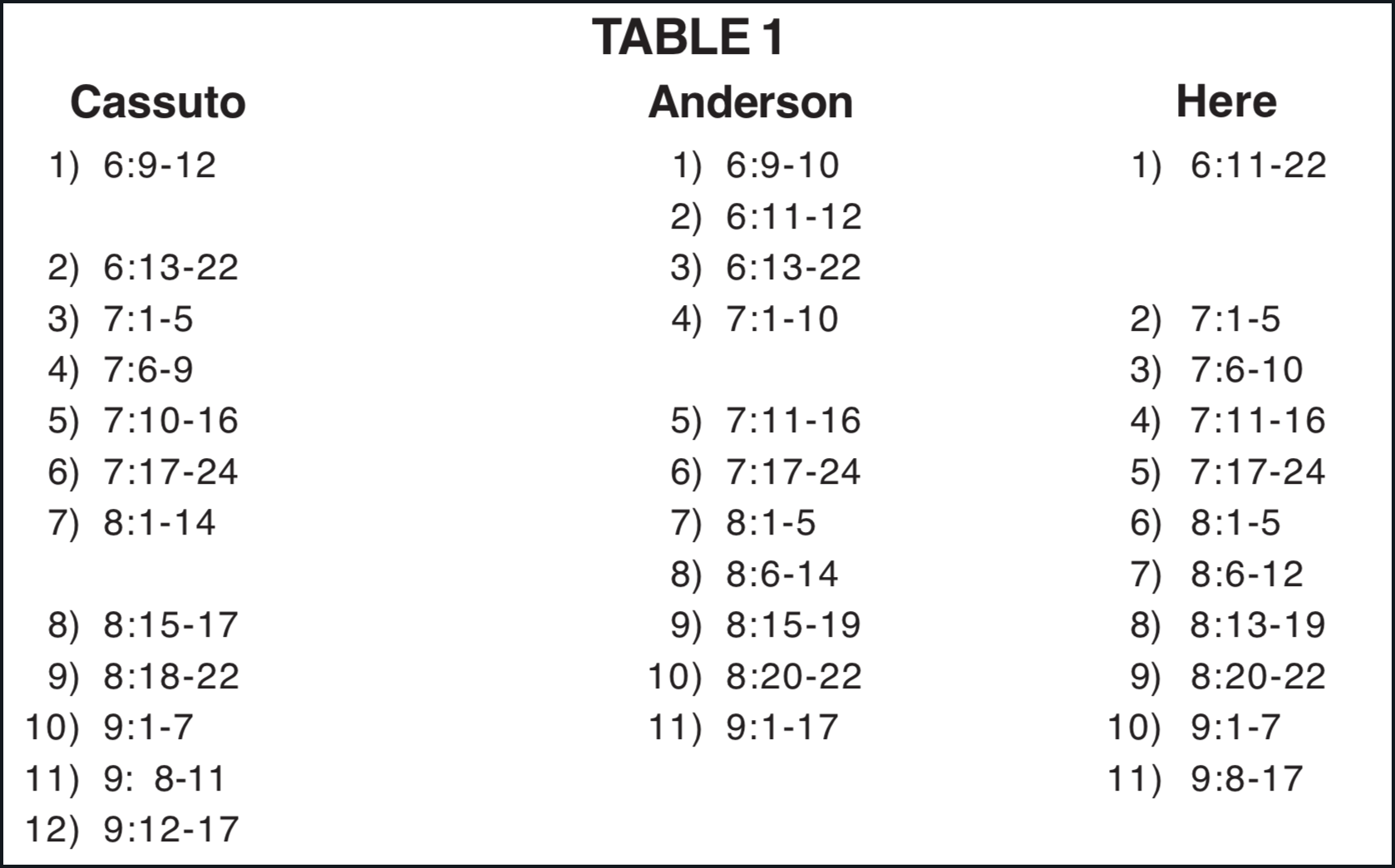

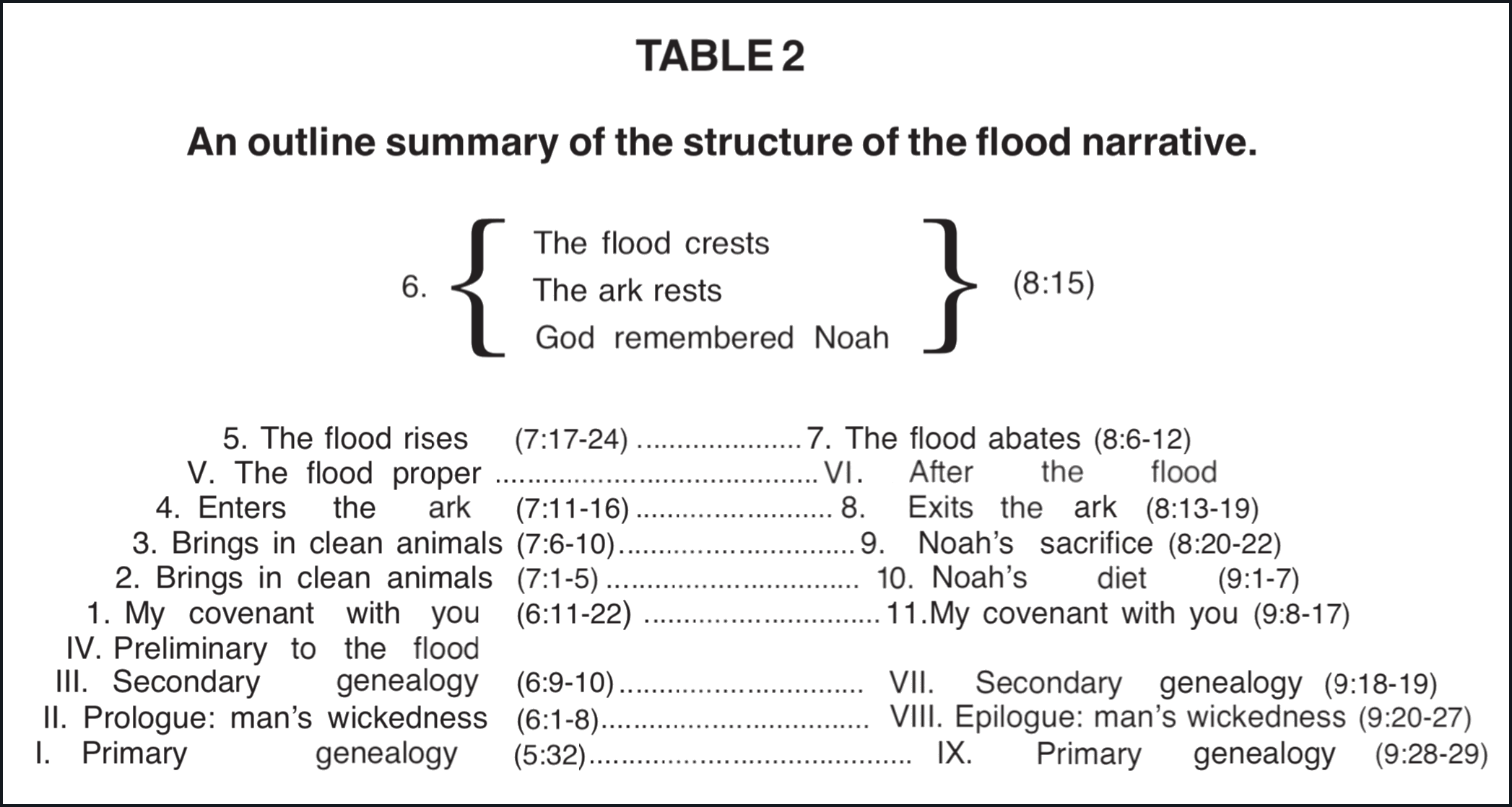

Both Cassuto and Anderson divide the flood narrative into 12 units, but the 12 units are divided somewhat differently in their respective outlines, as can be seen in Table 1. My own analysis is included for the purposes of comparison which is discussed later.

Table 1 shows that Anderson has made two additional sections by dividing one of Cassuto's original sections, and he has reduced five other sections to two. He has also included the genealogical information in 9:18-19 in his outline whereas Cassuto excludes it. Anderson is more consistent than Cassuto, because 6:9, with which their outlines begin, also includes genealogical information. I have excluded both genealogical notices (see the discussion of the individual units from my outline below). Each section in these outlines constitutes a discrete sense or thought unit in the flood account. To separate the J and P sources, literary critics commonly cross the boundaries of these sense units, a procedure which is both unnecessary and unwarranted, as should become evident from the structural study of the flood narrative which follows.

If this were merely a study in dividing the thought units of the flood narrative, such an exercise would not be of special importance. The value of this preliminary step is accentuated by the fact that these sense units are used as building blocks in the structure of the flood account in a very specific way, as Cassuto notes:

The series of paragraphs is composed of two groups, each comprising six paragraphs: the numerical symmetry should be noted. The first group depicts for us, step by step, the acts of Divine justice that bring destruction upon the earth, which has become filled with violence; and the scenes that pass before us grow increasingly gloomier until in the darkness of death portrayed in the sixth paragraph there remains only one tiny, faint point of light, to wit, the ark, which floats on the fearful waters that have covered everything, and which guards between its walls the hope of future life. The second group shows us consecutively the various stages of the act of Divine compassion that renews life upon the earth. The light that waned until it became a minute point in the midst of the dark world, begins to grow bigger and brighter till it illumines again the entire scene before us, and shows us a calm and peaceful world, crowned with the rainbow that irradiates the cloud with its colours a sign and pledge of life and peace for the coming generations [6].

Here Cassuto has described an elaborate literary chiasm in which the units correspond in the pattern of A:B:C:D:E:F::F:E:D:C:B:A. Thus there is not only a development of the flood account in the form of a crescendo to its greatest height, followed by a decrescendo, but the units with which this crescendo-decrescendo narrative is told are thematically paired between its first and second halves. Cassuto describes this phenomenon:

There is a concentric parallelism between the two groups. At the commencement of the first, mention is made of God's decision to bring a flood upon the world and of its announcement to Noah; and at the end of the second, reference is made to the Divine resolve not to bring a flood again upon the world and to the communication thereof to Noah and his sons. In the middle of the first group we are told of the Divine command to enter the ark and its implementation is described; in the middle of the second, we learn of God's injunction to leave the ark and of its fulfillment. At the end of the first group the course of the Deluge is depicted, and at the beginning of the second its termination [7].

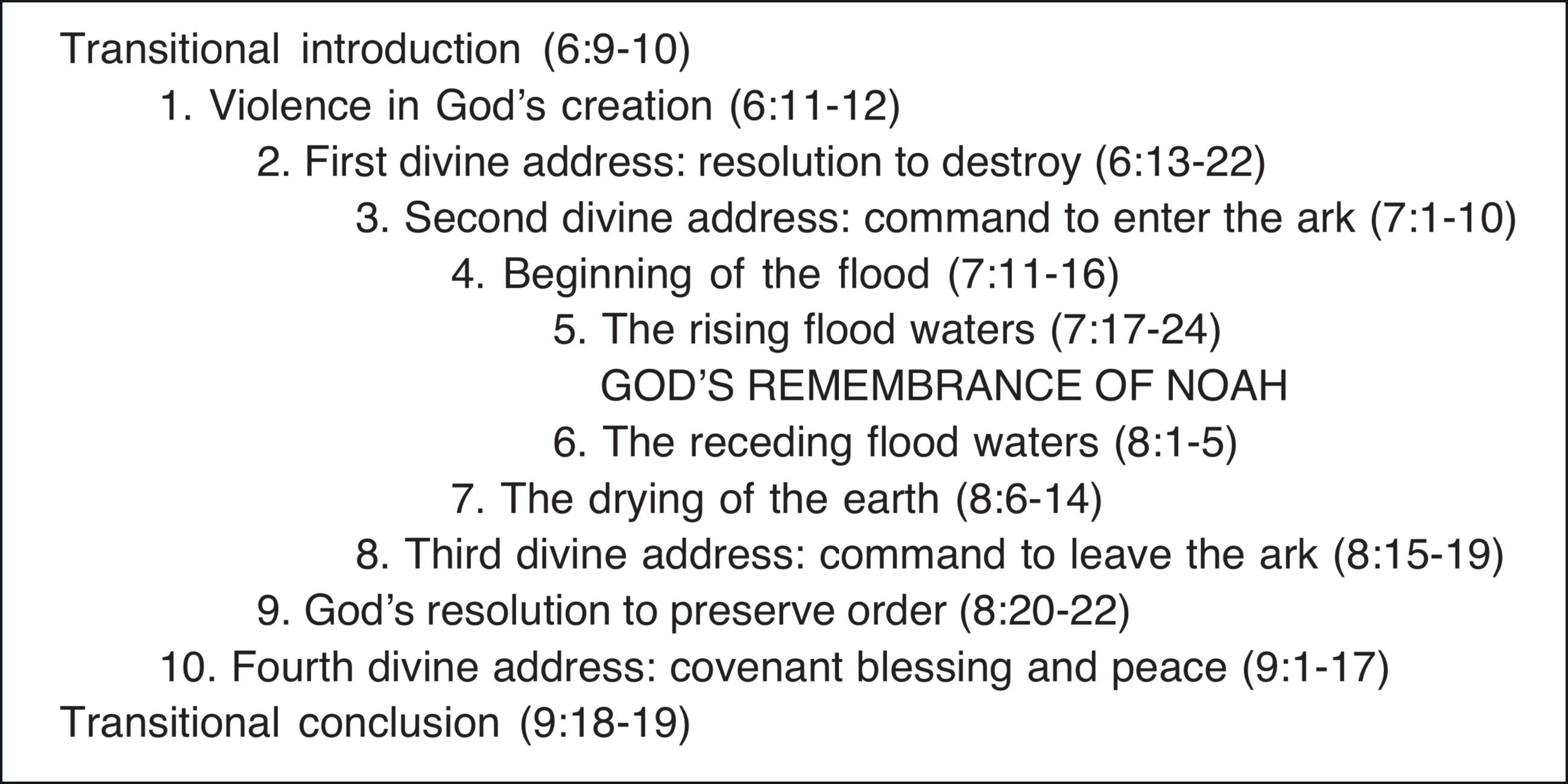

Anderson has come to the same general conclusion, though differing in some details, in his summary outline of the flood account [8].

My remarks will build upon the observations of these two scholars and are merely meant to amplify and refine some of their conclusions.

I. THE STRUCTURE OF THE FLOOD NARRATIVE

A. The Frame or Envelope for the Flood Narrative

1. The Primary Genealogical Inclusio (5:32 // 9:28-29). The genealogy of Genesis 5 gives only the first half of its standard formula related about Noah his birth age and the names of his three sons born thereafter. This formula, completed at the end of Genesis 9 where Noah's death age is given, forms the link between the genealogy of Genesis 5 and that of chapter 10, which records the Table of Nations descended from Noah's sons. Both halves of Noah's genealogical formula enclose the lengthy narrative about the flood; thus this bipartite genealogical statement functions specifically as a frame, an envelope, or an inclusio around it.

2. The Prologue and the Epilogue (6:1-8 // 9:20-27). Cassuto stresses the connection of 6:1-8 with the passages it precedes. In fact, 6:1-8 is the last passage treated in the first volume of his commentary on Genesis, whereas his second volume begins with 6:9 and the story of the flood [9]. Anderson's evaluation of the position of this passage is more perspicacious, since he notes how well it balances with 9:20-27 [10]. I am indebted to Anderson's analysis for the almost self-evident terminology of "prologue" and "epilogue" for these passages. Beyond that, however, I would suggest that both are enclosed by secondary genealogical statements (see below) and that the theme of the prologue tells why the epilogue was included in the text.

God and man are the two major elements in 6:1-8. Four statements are made about God in this passage: His view of the wickedness of man, His sorrow for creating man who had become so wicked, His determination on that account to blot man and the animals from the surface of the earth, and His designation of 120 years as the period of time to elapse until His purpose was to be accomplished. Of this passage Speiser has noted:

The story of the primeval titans emerges as a moral indictment, and thereby as a compelling motive for the forthcoming disaster. And the period of 120 years becomes one of probation, in the face of every sign that the doom cannot be averted. All of this accords with the separately established fact that the Flood story in Genesis, unlike its Mesopotamian analogues, was morally motivated [11].

This passage also records five significant facts about antediluvian man: the sons of God married the daughters of men; the daughters of men bore sons to those sons of God; the wickedness at this time was very great; and among the men of that time Noah found favor in God's sight. The term "sons of God" has occasioned much discussion in the commentaries. These sons of God are commonly thought to be divine-like beings, i.e., angels, because the identification of the sons of God as human beings does not otherwise occur until considerably later in biblical literature, whereas in non-biblical Canaanite texts, members of the pantheon were known as sons of El, the chief God.

Such an interpretation can only be held at the expense of doing considerable violence to the contents and context of this passage. The first line refers to the time when man ('adam) began to increase on the earth. This introductory statement puts the sons of God in relation to those men who spread over the earth and furthermore is a direct connection with the two genealogical lists which precede this passage. The list of Genesis 4 presents the "sons of men" to whom those daughters were born, the line of Cain that perpetuated his wickedness and violence. Genesis 5 presents the contrasting line of Seth, the line of faith, as the sons of God. Luke saw this connection when he wrote up his genealogy which ended with "Adam, the son of God" (Luke 3:38). Juxtaposing the reference to the sons of God and the daughters of men immediately after the genealogies of Genesis 4 and 5 strongly implies that these two groups belong to the two groups identified in those lists. Yet these two groups obviously included more than just the persons named in the genealogies, as there was an ever-expanding but otherwise unnamed population related to the persons identified in those lists. To inject angels into this scene is to insert an extraneous element into this passage and its context.

This passage begins and ends with two groups of men, the sons of God and the sons (fathers-daughters-sons) of men. The former is represented by Noah who found favor in God's sight, while the latter, more inclusive group received the condemnation and sentence of God for its wickedness. The principal purpose of this passage is to show that the wickedness of antediluvian man was the cause for the flood. Some relations with this theme are evident in the Epilogue to the flood narrative in 9:20-28. Mankind is not yet divided into the two great groups of good and evil, but the seeds of such a development and division already were laid in Noah's drunkenness and Ham's conduct toward his father. These were the best men whom God could find to bring through the flood. The correspondence in theme between the Prologue and the Epilogue to the flood narrative is, therefore, that of the wickedness of man before the flood and the wickedness of man even the best of men but on a lesser scale after the flood. The relationship between these two passages provides an additional explanation for the presence of the latter in the text when it has previously been interpreted largely in terms of the fate of Canaan (v. 25). Verses 25-27 parallel the patriarchal poetic prophecies given in terms of blessings and cursings by Isaac (Genesis 27:27-29), Jacob (Genesis 49), and Moses (Deuteronomy 33).

3. The Secondary Genealogical Inclusio (6:9-10 // 9:18-19). Both Cassuto and Anderson include the genealogical notice in 6:9-10 with the central narrative in their outlines of the flood account. Since 6:9-10 and 9:18-19 stand in similar positions at opposite ends of the narrative, they should be treated alike. Anderson is consistent in including both with the central body of the narrative; I prefer to exclude both. If the divided genealogical notice in 5:32 and 9:28-29 forms an inclusio around the flood account as a whole, these parallel genealogical notices should be evaluated in a similar way. Genesis 6:9-10 demarcates the Prologue from the central narrative which follows it, and 9:18-19 divides the central narrative from the Epilogue which follows it. Both of these brief passages contain lists of Noah's sons. The first list is identified as the "generations" (toledoth) of Noah, while the second refers to their exit from the ark and states that the world was populated (literally, "dispersed") from the three sons.

To summarize, up to this point we have detected the following structure for the envelope around the flood narrative proper primary genealogical inclusio:Prologue:secondary genealogical inclusio::(central narrative discussed below)::secondary genealogical inclusio:Epilogue:primary genealogical inclusio. We turn now to consider the sections with which the central narrative was composed.

II. THE BODY OF THE ACCOUNT, THE CENTRAL FLOOD NARRATIVE

A. Preceding and Following the Flood

1.The First and Last Divine Speeches: The Pre- and Post-Diluvial Covenants (6:11-22 // 9:8-17). The first and last sections of the body of the narrative contain the first and last and longest of the statements made by God to Noah. The first speech begins with the announcement of God's intention to destroy all flesh because of the violence and corruption that had spread abroad on the earth. No element in the final section corresponds directly to this theme, but, as Cassuto and Anderson have noted, linguistic relations are involved in the use of the word shahat, "corrupt, destroy." The first section contains a play on the different meanings of this word: the corruption of the earth and all flesh in it is noted three times and God stated twice that He would destroy all flesh because they had corrupted their way. In the final section the same verb is used twice of God's non-activity, for He covenanted never to destroy all flesh again with a flood. In a sense, therefore, antithetic parallelism exists between these two sections yes, a flood; no, no more floods. There is no parallel to the instructions for the construction of the ark in the final section, because the ark had already served its purpose.

Immediately after instructing Noah to build the ark, God described His plan to destroy man and the animals by a mabbûl, a "flood." This interesting word, used 13 times in the Hebrew Bible, refers solely to the Noachian flood. It occurs once in the first section (6:17) referring to what God would send, and then is used three times in the final section, as if to emphasize the point, referring to what God would not send (9:11, 15).

Then follows the most direct link between these two sections their covenants. The word "covenant" occurs only once in the first section (6:18), and seven times in the final section (9:9, 11-13, 15-17), as if to reemphasize the point. The verb used with the covenant in the first section, "to establish" (literally, "to cause to raise up"), is again used with the covenant three times in the final section. While the terms of these two covenants may not appear to be very similar at first glance, in actuality they are essentially the same in character. In both instances protection from a flood was offered during the flood in the first instance and from any future flood in the second.

The parties involved in these two covenants are also similar. The first covenant was made only specifically with Noah, but his immediate family and the animals are connected directly in the text as sharing in its benefits with him. In the second instance the covenant was made with Noah (four times), his descendants (once), the animals (once), and "every living creature of all flesh" (four times). The word for covenant does not occur in any other section of the flood narrative. These two sections are related most specifically, therefore, by means of the records of the covenants which they contain.

Both Anderson and Cassuto begin the central section of the flood account with 6:9-10, whereas I have separated the genealogical notice in these verses from what follows, for the reasons explained above. In addition, Anderson has divided 6:11-12 from the rest of this first section. Since God's initial statement to Noah in verse 13 stems directly from what He saw as recorded in verses 11 and 12, there is no reason for dividing the earlier verses from the latter.

2. The Preservation of and Second Purpose for the Animals (7:1-5 // 9:1-7). Cassuto concludes the first of these two sections with 7:5, whereas Anderson extends it to 7:10. Cassuto's arrangement is preferable, because the first five verses convey God's command to enter the ark, while the next five verses describe the first of two parallel statements about Noah's compliance with His command. The first section ends with the statement that Noah did all that Yahweh commanded. The second begins with a dateline and ends with a similar statement, that Noah went into the ark as God commanded him. This command, as reported in God's second speech to Noah, was given because a 40-day rainstorm would begin in 7 days and would blot out every land-based animal outside of the ark from the face of the earth.

Then Noah was told to take into the ark seven pairs of clean animals and birds but only single pairs of unclean animals. Source critics have long posed a numerical contradiction within the flood account, since in the preceding section only single pairs of all the animals were cited as candidates to board the ark. The difference in the number of animals, according to their analysis, stems from different sources, P and J respectively, but the methodology employed in differentiating such sources is inconsistent. The dimensions of the ark in the preceding section belong to P, because he "loves to fiddle with figures" [12]. By the same line of reasoning the numerical values attached to the different groups of animals that were to enter the ark should also be attributed to P, who should have been the most interested in the distinction between clean and unclean animals, but instead this passage is generally attributed to J. In such a bind, the source critic proposes that P has reworked J, but that admission means there really is no valid basis for distinguishing between such supposed sources here.

There are better explanations for this difference. First, it should be noted that 120 years passed between the events described in these two passages. At the end of Genesis 6, God referred to animals in more general terms when He commanded Noah to build the ark. The more explicit command came when the ark was completed presumably 120 years later. Thus a logical progression with the passage of time is seen. The same point is applicable to the flood itself. In the preceding section God only told Noah that He would blot out life on the earth by a flood. Now Noah is told that the flood would begin in 7 days and last for 40 days, another case of increasing specificity with the progress of the narrative.

Parallels for a progression of thought can be found in the prophets. Note, for example, the development of the theme of the remnant in the book of Jeremiah. In the early chapters are found only hints or brief statements about the remnant to be saved from the Babylonian destruction. By chapters 30-33, a detailed picture of the restoration of the remnant known as the Book of Consolation has been fully developed. In Genesis 6, Noah was given in essence a prophecy concerning the flood and was told to make provision to preserve a remnant this family and the birds and animals in an ark [13]. That more specific information was given later to Noah about the remnant and the flood through which they would be saved is no more surprising than that more specific information was given to Jeremiah later in his ministry about the remnant that was to be saved out of the Babylonian destruction.

A further explanation for the mention of the number of clean animals and birds comes from. the parallels between this section and its corresponding member in the second half of the flood account, which gives the instructions to Noah concerning the diet of mankind after the flood. At this point one might expect to find provisions being made for the new diet which was to include the flesh of animals. It is interesting to note, therefore, that relatively greater quantities of clean animals were provided to meet this need. While there is no explicit command at this time to abstain from unclean meat, a portent of such future instruction is contained in the differentiation between the relative quantities in the two groups of animals.

The other main point in Genesis 9:1-7 is that man was prohibited from taking the blood or life of other men, i.e., the permission given to slay animals (for food) was not to be extended to slay man for whatever reason. Perhaps this question arose because God was the one who slew mankind with the flood, according to the first of these two passages. Could man then slay his fellow man with impunity in view of such divine conduct? The answer is: No, that prerogative was to be left to the judgment of God alone. Thus these two sections share synthetic and antithetic themes. The synthetic theme is the preservation of the animals in order to provide man's post-flood diet. The antithetic element is that God could blot men from the face of the earth (i.e., with the flood), but man was not to usurp the divine prerogative of judgment by taking the life of a fellow man.

3. The Preservation of and First Purpose for the Animals (7:6-10 // 8:20-22). Both Cassuto and Anderson conclude the first of these two sections with 7:10. My contents for the second of these two sections correspond to Anderson's, while Cassuto's section includes Noah's departure from the ark with his offering of sacrifices. Noah's departure from the ark fits better with the preceding verses, as the response to God's command to leave the ark, which leaves the sacrifice scene standing alone as a separate unit.

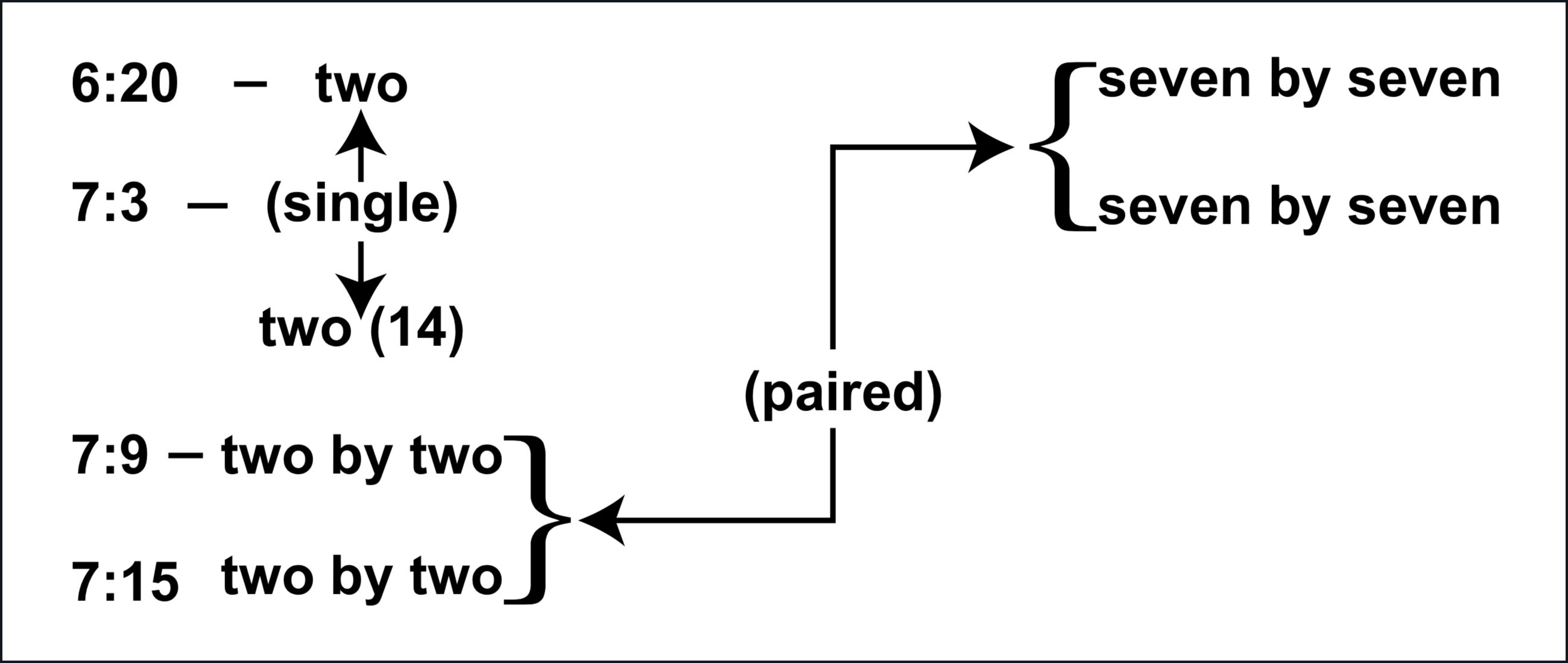

Once again the birds and animals provide the thematic link between these two sections, and once again the clean and unclean are divided. Before the onset of the flood, four passages deal with the number of animals that were taken into the ark. The difference between 6:20 and 7:3 has already been discussed above. In 7:9 the distinction between the clean and the unclean animals continues, and they went into the ark "two (by) two." The same numerical value accompanies the reference to the animals in 7:15. Source critics commonly attribute the references to two (6:20) and two by two (7:15) to P, while the seven by seven in 7:3 is attributed to J. Because the two by two in 7:9 does not fit well with the rest of the formulae in 6:20 and 7:15, it is usually attributed to a later editor or redactor (R) and is thus disqualified as a primary source. No textual evidence is available to support this interpretation; it rests solely upon a hypothesis of this mode of literary criticism.

The animal formulae of these four passages contain three main elements: numerical values to quantify them, the phraseology employed for the animals themselves, and distributional terminology which categorizes the animals according to their types. Taking the numerical values first, we find the following distribution for these units in the Hebrew text:

The link between 6:20 and 7:15 as proposed by source critics does not hold up when analyzed from the viewpoint of their numerical values, since the numerical value of 7:15 is reduplicated, as are those of 7:3 and 7:9, whereas the only specific numerical link of 6:20 is with 7:3, where the unclean animals are still quantitated by the number two written singly. Thus the numerical portions of these formulae cross their proposed sources, since 6:20 and 7:3, supposedly written by P and J respectively, are the only passages that contain the number two written singly, and both 7:3 and 7:15, J and P supposedly, contain reduplicated numerals. Neither is there any valid reason to attribute 7:9 to J and 7:15 to P, since they both reduplicate the same numeral two. The way in which the numerical values were written in these four passages lends no support to separating any J and P sources, for they form an interrelated and progressive series. Nor is there any conflict between the two by two of 7:9 and 15 and the seven by seven of 7:3. The best way to translate the "two by two" of 7:9 and 15 is probably "by pairs," referring to the male-female pairs, while 7:3 indicates specifically that seven of those "clean" pairs were to be taken into the ark.

All four passages use the same word for beast or animal (behemah) and for fowl (côp). In 7:3 "heaven" is added, while 7:15 adds a new phrase "every bird of every wing." Both this reference to the birds and the one in 6:20 have been attributed to P, but this position can only be maintained by interpreting the additional phrase for the birds in 7:15 as an expansion or gloss upon the more abbreviated reference in 6:20. A similar expansion must also be posited for the animals that creep upon the ground. Reference to this class of animals is only found in 6:20 and 7:15, not in 7:3 and 9. In 6:20, however, this class is identified as the "creeper of the ground," whereas in 7:15 it is identified as the "creeper that creeps upon the earth." The root for "creep" is reduplicated in the second passage and contains a different word for earth which is used with a preposition rather than in a construct phrase as is the case with 6:20. In order to relate these two passages by source, therefore, one must contend with the fact that the phrases which refer to the birds and the animals that creep on the ground differ by a total of seven Hebrew words.

Analysis of the distributional terminology employed in these formulae provides an explanation for the presence of the creepers of the ground in the first and fourth passages and their absence from the second and third. In general, they fall into the category of unclean animals. Thus in the two passages in which the clean and unclean are differentiated, the creepers of the ground are not distinguished, whereas in the two passages in which the clean and the unclean are not differentiated, the creepers of the ground are present. The same distinction applies to the use of the phrase "according to its kind" (1emînehû) which also appears only in the first and fourth passages. When the "kinds" are broken down into clean and unclean, as in the second and third passages, the distributional term is not employed.

Thus these four passages divide into two pairs according to their distributional terminology. This does not mean that they should be attributed to different sources; it indicates instead the pattern in which they were used through this portion of the flood account: according to its kind:clean/unclean::clean/unclean:according to its kind, or A:B::B:A. Thus the first and fourth general statements were connected with the initial command to build the ark for these animals and the final statement that they had entered the ark. When Noah was commanded to enter the ark, these classes were broken down more specifically, as would be expected on that immediate occasion, and a parallel statement of compliance to these specifications is given also in those terms. Source critics commonly refer to such passages as duplicates and attribute them to different sources. In so doing they have missed the literary technique of parallelism employed by the ancient Semites in their poetry and prose. Thus the formulae employed in referring to the animals in these four passages do not provide criteria, by which they should be separated into sources. On the contrary, they provide evidence for the design of literary structure in the account. Additional evidence for the structure comes from considering the parallels that are found in the four sections which follow the central-most elements of the account.

The reference to the clean animals in 7:9 is of importance in evaluating the relationship of this section with its parallel member from the second half of the flood account, in which Noah selected his sacrificial offerings from the clean birds and animals. Just as God provided the clean animals in greater abundance for man's food after the flood (see the preceding section), He also provided them in greater abundance for their use in sacrifice. An obvious practical point is also involved. Had Noah sacrificed a member from the pairs of the unclean animals, there would have been no mate for the remaining member of those pairs; consequently none of the unclean animals would have been able to propagate after the flood.

When the references to the animals in these four sections are compared with their parallel sections in the second half of the account, it can be seen that the distinction between the clean and unclean animals is made in the two sections which correspond to the two sections in which that distinction was most vital to man after the flood those referring to the use of animals for sacrifices and for food. The parallel members to the two sections which lack this distinction deal with all of the animals coming out of the ark and all of the animals enjoying the benefit of the covenant that God made with Noah and his descendants never to destroy the earth again by a flood. Since both clean and unclean animals participated in these two events, there was no need to distinguish between them in the parallel sections earlier in the flood narrative.

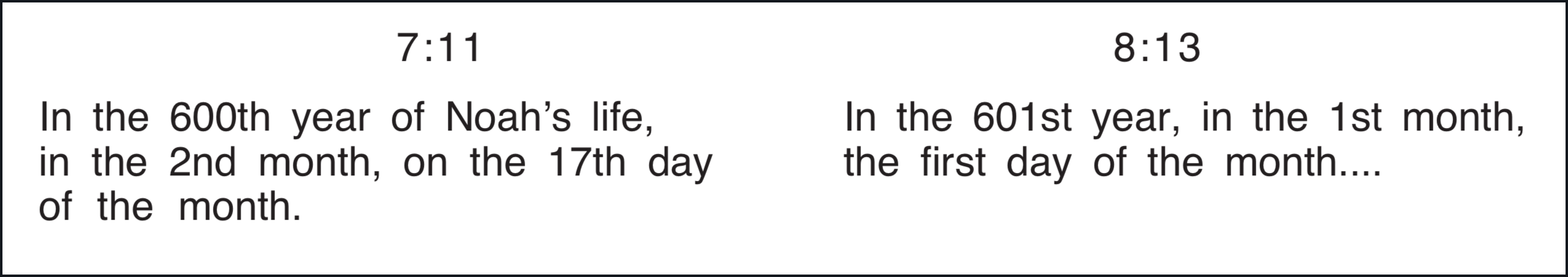

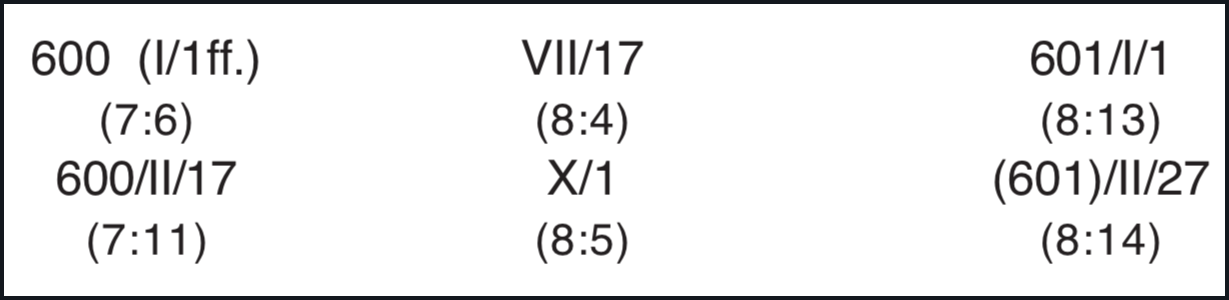

4. Entering the Ark and Leaving the Ark (7:11-16 // 8:13-19). The major parallels between entering the ark and leaving the ark are self-evident. The verbs employed for these actions, bô' and yasa', are reciprocals. To expand upon the parallels between these two sections, it may be noted that both begin with a rather precise date in terms of Noah's life:

These are the only two passages in which this full-date formula occurs in the flood account. Immediately after these dates the first section tells how the waters came upon the earth, and the second section states that the waters had dried from off the earth. Both sections continue with references in the same order to Noah's family and the birds and animals. For further reciprocal actions between these two sections, note that Yahweh shut Noah in the ark at. the end of the first section, whereas Noah removed the covering from the ark at the beginning of the second. Similar sounding verbs are used to describe these two actions. The first section describes the two sources from which the waters of the flood came and the second section tells of the drying of the earth in two stages. The departure from the ark is described in terms of the divine command to depart from the ark and the statement of Noah's compliance with that command. The reference to the birds and animals being fruitful and multiplying upon the earth harks back to the record of creation. Thus the repopulation of the earth after the flood parallels the population of the earth at creation.

These are the only two passages in which this full-date formula occurs in the flood account. Immediately after these dates the first section tells how the waters came upon the earth, and the second section states that the waters had dried from off the earth. Both sections continue with references in the same order to Noah's family and the birds and animals. For further reciprocal actions between these two sections, note that Yahweh shut Noah in the ark at. the end of the first section, whereas Noah removed the covering from the ark at the beginning of the second. Similar sounding verbs are used to describe these two actions. The first section describes the two sources from which the waters of the flood came and the second section tells of the drying of the earth in two stages. The departure from the ark is described in terms of the divine command to depart from the ark and the statement of Noah's compliance with that command. The reference to the birds and animals being fruitful and multiplying upon the earth harks back to the record of creation. Thus the repopulation of the earth after the flood parallels the population of the earth at creation.

B. The Course of the Flood: The Central-most Sections of the Flood Narrative

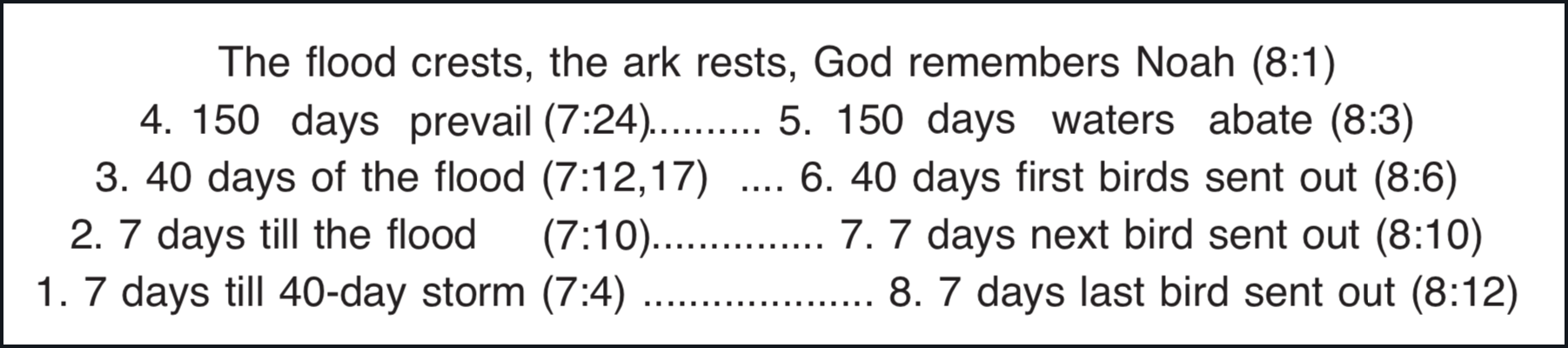

5. The Flood Waters Rise and Abate (7:17-24 // 8:6-12). My sections resemble Anderson's, but, I have ended the second section two verses earlier. The dateline in 8:13 is best interpreted as the heading for this next section. Cassuto considers all of 8:1-14 to be one section, overlooking the dateline of forty days with which both sections begin. The first chronological reference delimits the period of time during which the flood waters increased upon the earth until they covered the mountains. The second period of forty days began when the tops of the mountains first reappeared and Noah sent out the first of the birds with which to test the state of the world outside the ark.

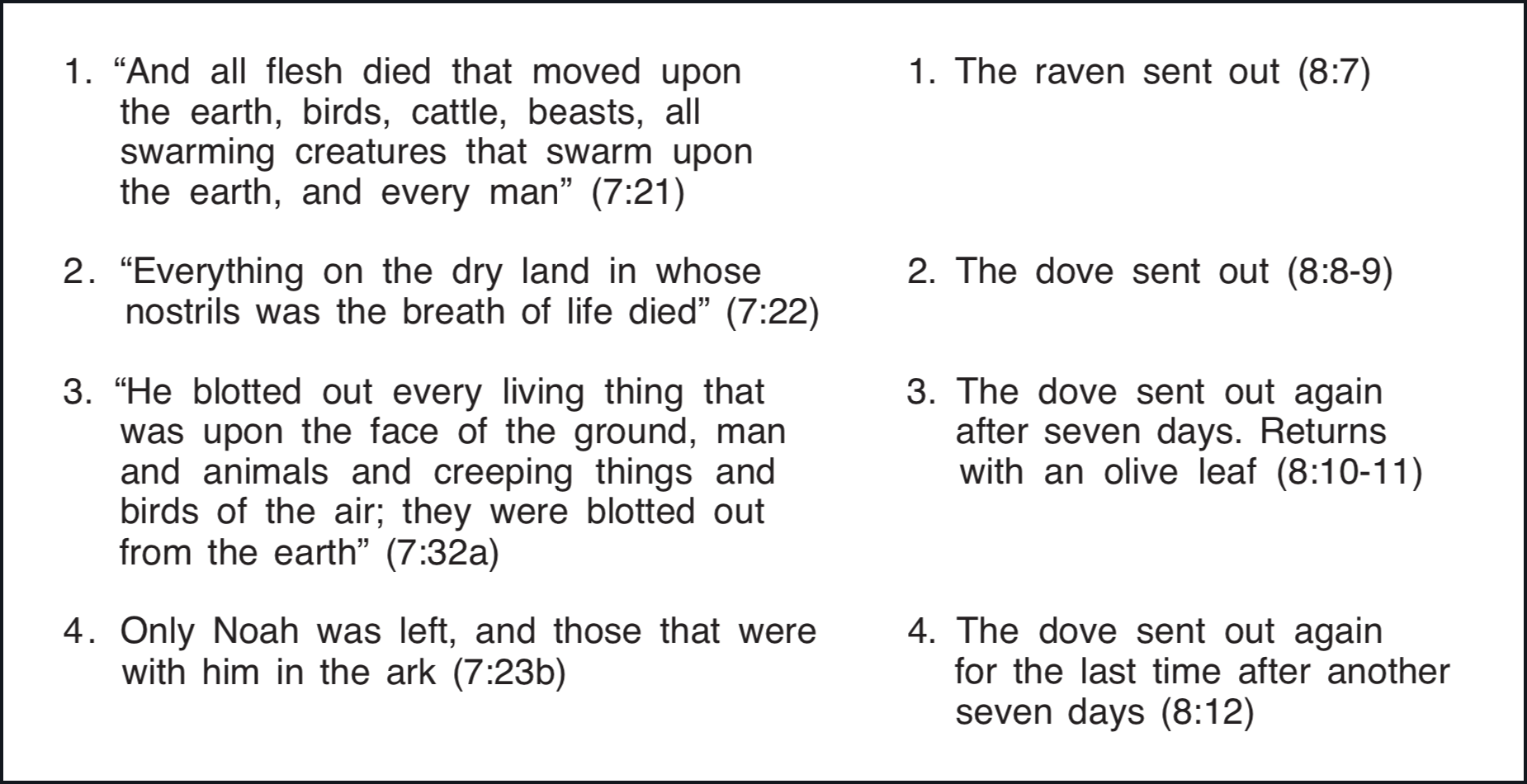

Thus the first section tells of the disappearance of the last trace of life outside the ark, retelling it four times over to emphasize the point. The story of the reappearance of life outside the ark is also told four times, each time involving the appearance of a bird outside the ark. These two parallel constructions can be outlined as follows:

Comparing the subdivisions of these two sections with the preceding and following sections shows that four sections lead up to the flood and four sections follow it, while within each section describing the rise and fall of the flood are found four statements or subsections that relate to the disappearance and reappearance of life outside the ark. With this balance between these two sections it seems very unlikely that 7:17-24 should be divided into four sources (P/J/P/J) and 9:6-12 should be divided into three sources (P/J/P), as literary critics have proposed.

6. The Apex of the Flood, the Climax of the Flood Account (8:1-5). Anderson has called attention to this section as "the turning point of the story with the dramatic announcement of God's remembrance of Noah and the remnant with him in the ark" [14]. I differ with Anderson and Cassuto as to the structural expression of this climax. In their analyses both Anderson and Cassuto subdivide the flood account into twelve sections, which gives them six even sets of "two by two." Yet if the preceding analyses have been correct, the narrative approaches this climax through the crescendo of the flood waters in 7:17-24 and their decrescendo through 8:6-12. Since these two sections parallel each other, 8:1-5 stands alone at the climax of the story the apex of the flood waters figuratively, on the very tops of the mountains of Ararat. This pattern which peaks at this point thus emphasizes the manner in which the structure of the narrative contributes forcefully to its intent, i.e., its form complements its function. The complementary themes of this section are expressed in three brief statements: the flood crests, the ark rests, and God remembered Noah. Arriving at this climax brings us to a review of the overall structure of the flood account (Table 2).

III. THE CHRONOLOGICAL ELEMENTS IN THE FLOOD NARRATIVE

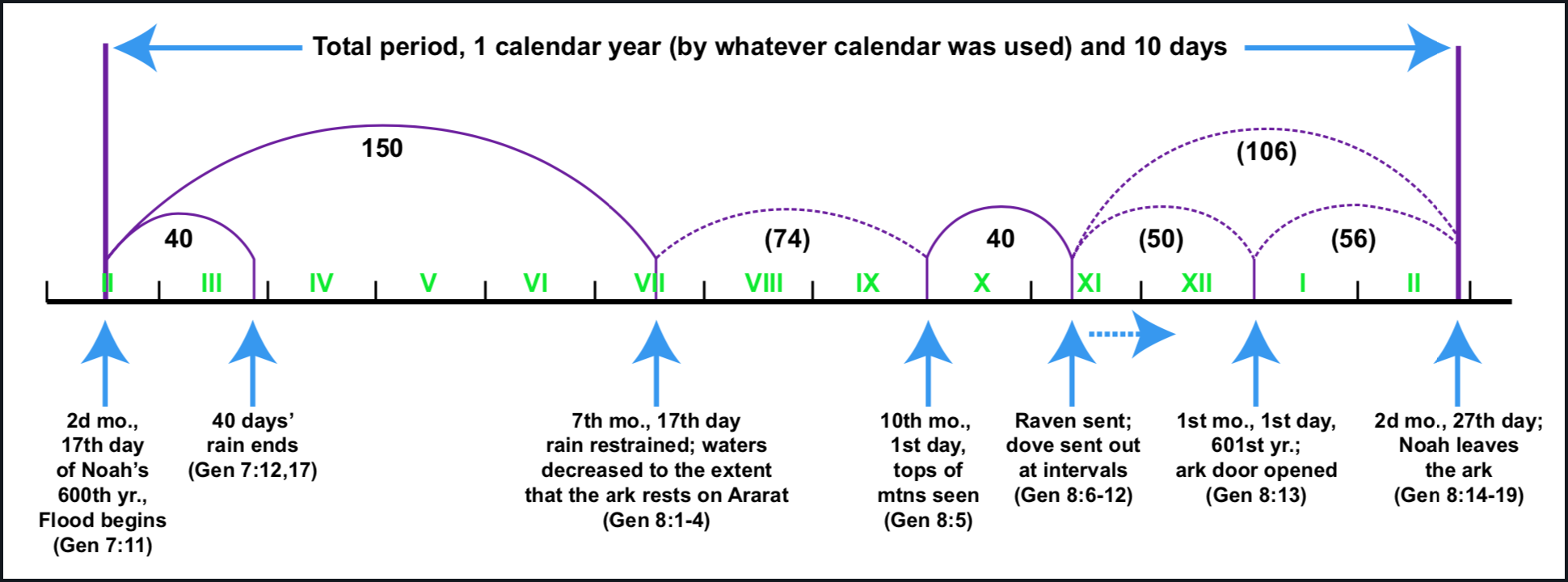

The biblical account of the flood contains a number of chronological references which can be divided into two categories. The first gives the length of time for certain periods between different events in the account, such as the 7 days, the 40 days, and the 150 days that elapsed between such events. The second gives more specific reference to certain points in time that are dated in terms of the day, month, and year of Noah's life.

A. Literary Criticism of the Dates in the Flood Account

Source critics have posited discrepancies between some of these chronological data in order to separate the J and P sources for the account. It is held that these two sources were not reconciled chronologically when they were fused together editorially. The statements about time periods have been credited to J, and the more precise chronological statements given in terms of Noah's life are attributed to P.

Source critics are inconsistent in applying this methodology, because they credit the 7 and 40 days to J while attributing the 150 days to P. If the time-period statements are characteristic of J, then the 150 days should also be given to J, but to do so would erase the desired distinction between the length of the flood in J and P.

Another defect of this method is the way in which these dates are excluded from the sections in which they are found. This occurs with four dates from Noah's life for P (7:6, 11; 8:13, 14) and twice for the 40 days in the case of J (7:12, 17). Moreover, in 7:17 a chronological statement is severed from the sentence in which it occurs: "the Flood came down upon the earth (P)/40 days (J)" [15]. Such treatment leads to a misunderstanding of the text as can be seen in a recent commentary on Genesis. The commentator observes that in the two differently dated statements about the drying of the earth (8:13-14), "we are confronted by two separate chronologies of the flood within the same source, a fact that should not too much disturb us in view of the complicated history of the legend" [16].

Closer attention to the Hebrew text would have prevented such an errant observation. This passage states that on 601/I/1 "the waters were drying up" (harbû hammayim). Later, at an unspecified time, Noah removed the covering of the ark and saw that the "faces of the ground, were drying up" (harbû penê ha'adamâ). By II/27, however, "the earth was dry" (yabeah ha'ares). Since three different subjects occur in these statements and since the verbs used in the two dated statements are different, it is quite arbitrary and unfair to the ancient writer to state that all have the same meaning. We may not understand the degree of distinction intended in using these two different verbs for drying, but the philological distinction remains nonetheless.

B. The Calendar for the Flood

The preceding section has discussed some of the difficulties with the methodology which attempts to sort sources on the basis of supposed discrepancies between the different chronological statements in the flood narrative. These difficulties lie more, I believe, in the defects of this methodology than in the chronological data. As Figure 1 demonstrates, all these data can be harmoniously integrated into one chronological scheme for the flood, according to the calendar constructed by S.H. Horn [17].

C. The Pattern for the Periodic Chronological Data

An additional aspect of the chronological statements is their pattern which contributes to the crescendo of the narrative to its climax and the subsequent decrescendo. All references to the time periods can be encompassed in the following outline:

D. The Pattern for the Specific Chronological Data

The chronological references given in terms of dates in Noah's life fit a similar pattern: two are given in the sections before the flood proper is described, two are given in the climactic section at the apex of the flood, and two follow the central-most sections of the flood narrative. Not all of the date elements (year/ month /day) are included in every reference, but their absences are also distributed according to a pattern which can be outlined as follows:

This outline and the preceding one shows a definite design to the way in which the chronological data of the flood were recorded. These two patterns follow and thus complement the pattern for the narrative that has been determined above from a literary analysis of its sections. Since all three elements the literary units, the time periods, and the dates are distributed according to similar and parallel patterns, it seems very unlikely that any one of the three should be attributed to a different documentary source. To attribute one kind of date to one source and the other kind of date to another source when they parallel each other so closely seems very unlikely from the viewpoint of valid literary analysis. No distinction between J and P can be derived from such data.

E. Literary Criticism of the Chronological Elements in Extrabiblical Flood Stories of the Ancient Near East

Four main flood stories from Mesopotamian sources are known: 1) a very fragmentary copy of the Sumerian version which dates to the early second millennium B.C. [18], 2) tablets of the Old Babylonian version known as the Atra-hasis Epic, which can be dated to the last half of the 17th century B.C. according to their scribal colophons [19], 3) an 8th or 7th century B.C. copy of the Neo-Assyrian version known as the 11th tablet of the Gilgamesh Epic [20], and 4) a flood story as recorded by Berossus, a Babylonian priest of the 3rd century B.C. [21]. Because of its late date the last source will not be discussed here. The Sumerian flood story will only be mentioned in passing because of its fragmentary condition.

Of particular interest are the chronological elements in the Babylonian flood stories, because source critics have commonly attributed these elements to P, when analyzing the Genesis flood account. Can the same methodology be applied to these ancient Near Eastern sources? The Atra-hasis Epic is a comprehensive story, covering the creation of man to the flood. Seventeen chronological data occur in the surviving portions of this epic.

The first chronological datum in the Atra-hasis Epic refers to a period of 40 years during which the lesser gods of the pantheon toiled in the cosmos. When they rebelled, the decision was made to reassign their burdensome tasks to man, who was to be created from clay and the blood and flesh of a god named We-ila. To prepare for this event, the god of wisdom ordered that purifying baths be taken, apparently by We-ila, on the 1st, 7th and 15th days of the month. A parallel repetition of this chronological statement states that the purifying baths were taken on those days. In the middle of the story are some regulations given by the birth-goddess for women bearing children, including the instruction that a woman should remain in confinement for 7 days after giving birth.

The birth-goddess gave birth to mankind, as stated twice in a parallel bicolon, in the 10th month of her gestation. Parallel statements inform us that 9 days were assigned for her confinement and the rejoicing connected with the creation. But the noisy population of the earth prevented the gods from sleeping, and before mankind had existed for 1200 years, the decision was made to decimate their ranks with a plague. This plot was foiled when the god of wisdom told Atra-hasis the human hero of the story to avert the plague by making offerings to the plague god.

After a second period of 1200 noisy years, the gods decided to decimate mankind by drought and famine. This time the storm god resupplied mankind with water after they built him a temple. The difficulties experienced during this famine are described as becoming progressively more severe through its 1st, 2nd, and 3rd years. The point was expanded in the later Assyrian version of this text.

Because the plague and famine had failed to solve the problem posed by mankind, the gods decided to send a flood as the final solution. Obeying instructions from the god of wisdom, Atra-hasis built an ark and was able to escape, along with his family and the birds and animals, from the flood. Only two chronological references occur in this portion of the story. As with Noah in the Bible, Atra-hasis was warned 7 days before the onset of the flood: "he (the god of wisdom) announced to him (Atra-hasis) the coming of the flood on the seventh night" [23]. The flood lasted seven days and seven nights [24]. The Sumerian version also indicates that the flood lasted seven days and seven nights, but about 40 lines are missing from the portion where one might have found reference to the length of time before the flood [25].

Utnapishtim is the name of the hero in the flood story told in the Gilgamesh Epic. Utnapishtim built the ark in two days, starting five days after the god informed him that a flood was coming and finishing it on the seventh day [26]. In contrast to the Atra-hasis Epic, this source gives a rather detailed description of the size and shape of the ark. A biblical literary critic would attribute these details, along with the chronological statements, to P. Utnapishtim's flood also lasted 7 days, and he waited another 7 days after landing before sending out his birds at intervals of unspecified lengths of time. Thus three main periods of time are present in this version of the flood: 7 days before the flood, 7 days of the flood, and 7 days after the flood. These periods of 7 days are broken down in the text, however, so that a dozen chronological references occur in the story.

In terms of chronology the biblical account of the flood is considerably more complex than either of the Mesopotamian flood stories. It contains five specific dates whereas they contain none. It also contains references to six different periods of 7, 40, and 150 days duration, while the Babylonian stories refer only to 2 or 3 periods of 7 days each. The broken Sumerian version refers to the 7 days of the flood, the Atra-hasis Epic refers to the 7 days before and during the flood, and the Gilgamesh Epic refers to the 7 days before, during, and after the flood. There are 17 chronological data in the entire Atra-hasis Epic, 16 in the biblical flood account, and 12 in Gilgamesh's version.

From this summary the question can now be asked, how should the chronological data in these two Babylonian flood stories be handled from the standpoint of literary criticism? If one were to follow the techniques of biblical source critics, most of these should be attributed to a P (C?) source, whereas much of the body of the story should be attributed to a J (Ah and G?) source. But no Assyriologist has ever suggested that these chronological details should be sorted out from these stories and attributed to another source other than that through which the main body of the narrative was received. I suspect that if such an approach to this narrative were proposed at a professional meeting of orientalists, it would meet with a very cool reception.

On April 12,1978, I attended a symposium on Sumerian literature at the annual meeting of the American Oriental Society in Toronto, Canada. Sumerologists are now able to analyze as literature the Sumerian myths and epics that have been recovered from cuneiform texts. At this symposium it was suggested that Sumerologists could learn from the techniques of literary criticism that have been practiced by biblical scholars for a century. One observer responded that the field of documentary analysis in biblical criticism was in chaos and disarray, and he recommended that Sumerology avoid getting bogged down in a similar morass.

This observation emphasizes the dichotomy in methodology between biblical and ancient Near Eastern studies. Instead of evaluating biblical literature according to the dead-reckoning canons drawn from Homeric studies of the last century, attention should first be given to the writing of the ancient Semites who lived in the same world as the biblical Hebrews. This has never been done thoroughly and consistently in biblical studies.

A further illustration of this problem is seen in a reaction to Ancient Orient and Old Testament (Inter-Varsity Press, 1966), by K.A. Kitchen, an English Egyptologist and conservative Christian who strongly rejects the documentary hypothesis. In a book review which appeared in 1970, E.F. Campbell, Jr., of McCormack Theological Seminary in Chicago, objected that "comparison of ancient Near Eastern law to the materials in Leviticus could lead a Speiser to suggest how old some of the Leviticus is, but the same Speiser could work very effectively with the J and E strands and with P in writing his Genesis commentary" [27]. But Campbell failed to realize that Speiser a professional Assyriologist never applied the methodology employed in his commentary on Genesis to the corpus of ancient Near Eastern extrabiblical literature. It is particularly important to note that Speiser followed a rather standard documentary approach to Genesis 6-9, but never deigned to analyze the Mesopotamian flood stories along similar lines.

IV. CONCLUSION

Even if my analysis of the literary structure of the biblical flood narrative is only approximately correct, the documentary analysis postulated by source critics in the past century cannot be correct. As it stands, the structure could only have come from the hand of one author. Its precise design far transcends any modifications that might have been introduced to mold such sources together by a later editor. Each section delimited above is a building block which contributes a very precise part to the elaborate crescendo:decrescendo design of the narrative. To remove any or to attribute them to separate sources differing in date by several centuries would require a total rejection of any literary structure in the flood account. In other words, the study of the literary structure of this narrative stands in direct opposition and tension to the previous documentary analyses that have been performed upon it.

On those rare occasions when this point is emphasized, source critics have suggested that P used J extensively and actively in writing up his account [28]. So extensive has been this supposed reuse of J that the two sources are essentially indistinguishable at present. But if J and P are no longer distinguishable from each other, then there is also no reason to maintain that such separate sources were ever involved. The author of the biblical flood account, as it currently stands, could have employed sources to compose his work, but in whatever form those sources may have come to him, they are not really recognizable beyond the current literary unity of the flood narrative. This re-examination of its structure has borne out Cassuto's comment on it in relationship to source criticism, and the point he makes is just as valid as when he penned it three decades ago:

If we examine the section of the Flood without bias and pay heed to its finished structure ... it becomes apparent that the section in its present form cannot possibly be the outcome of the synthesis of fragments culled from various sources; for from such a process there could not have emerged a work so beautiful and harmonious in all its parts and details. If it should be argued that the artistic qualities of the section are the result of the redactor's work, then one can easily reply that in that case he was no ordinary compiler, who joined excerpt to excerpt in mechanical fashion, but a writer in the true sense of the word, the creator of a work of art by his own efforts. Thus the entire hypothesis, which presupposes that the different fragments were already in existence previously in their present form as parts of certain compositions, collapses completely [29].

FOOTNOTES

[1]Speiser assigns the following sections to J: 6:1-8; 7:1-5; 7:7-10; 7:12; 7:16b; 7:17b; 7:22-23; 8:2b-3a; 8:6-12; 8:13b; 8:20-22; and 9:18-27. He assigns the following sections to P: 6:9-22; 7:6; 7:11; 7:13-16a; 7:17a; 7:18-21; 7:24 - 8:2a; 8:3b-5; 8:13a; 8:14-19; 9:1-17; and 9:28-29. E.A. Speiser, 1964, Genesis, Anchor Bible, vol. 1, Doubleday, Garden City, New York, passim.

[2]Ibid., p. 54.

[3]U. Cassuto, 1964, A commentary on the book of Genesis, vol. II, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, pp. 30ff.

[4]B.W. Anderson, 1978, From analysis to synthesis: the interpretation of Genesis 1-11, Journal of Biblical Literature 97:23-29.

[5]See also S.E. McEvenue, 1971, The narrative style of the Priestly writer, Analecta Biblica, vol. 50, Pontifical Biblical Institute, Rome, pp. 35ff. McEvenue has also studied the structure of the flood narrative to some extent, but his study is complicated by the fact that he examined only those passages which he attributed to P; hence his study is incomplete for the purposes of the analysis presented here. Another similar study has been done by G.J. Wenham, 1978, The coherence of the flood narrative, Vetus Testamentum 28:336-348. Wenham and I concur that the climax of the narrative in 8:1 stands alone and the parallels begin on either side of it; he also places more emphasis upon the parallelisms between the chronological elements in the two halves of the narrative. In contrast to my study, however, Wenham divides the narrative into 31 smaller units, and his does not include the prologue or epilogue, which he did not analyze. His conclusion is that Genesis 6-9 forms one complete literary unit that cannot be divided into different sources without disruption of the structural integrity of this account.

[6]Cassuto, Genesis, pp. 30-31.

[7]Ibid., p. 31.

[8]Anderson, From analysis to synthesis, p. 33.

[9]Cassuto, Genesis, pp. 3ff.

[10]Anderson, From analysis to synthesis, p. 33.

[11]Speiser, Genesis, p. 46.

[12]B. Vawter, 1977, On Genesis: a new reading, Doubleday, Garden City, New York, p. 118.

[13]For a discussion of the theme of the remnant, see G. Hasel, 1972, The remnant: the history and theology of the remnant idea from Genesis to Isaiah, Andrews University Press, Berrien Springs, Michigan.

[14]Anderson, From analysis to synthesis, p. 36.

[15]Speiser, Genesis, p. 49.

[16]Vawter, On Genesis, p. 129.

[17]S.H. Horn, 1960, Seventh-day Adventist Bible dictionary, Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington, D.C., p. 355. For a more detailed discussion of the calendar involved here, see L.H. Wood, 1953, The chronology of Ezra 7, Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington, D.C., pp. 49-53.

[18]As translated by M. Civil, in W.G. Lambert and A.R. Millard, 1969, Atra-hasis: the Babylonian story of the flood, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 138-145.

[19]Lambert and Millard, Atra-hasis, pp. 31-32.

[20]As translated by E.A. Speiser, in J.B. Pritchard, ed., 1955, Ancient Near Eastern texts relating to the Old Testament, Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp. 93-96, hereinafter referred to as ANET.

[21]Lambert and Millard, Atra-hasis, pp. 134-137.

[22]Ibid., p. 45. The other chronological data mentioned from this text follow in this work passim.

[23]Ibid., p. 91.

[24]Ibid., p. 97.

[25]Ibid., p. 143.

[26]ANET, pp. 93-94. The other chronological data mentioned from this text follow in this work passim.

[27]E.F. Campbell, Jr., 1970, Book review of K.A. Kitchen's Ancient Orient and Old Testament, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 29:137.

[28]This is Anderson's solution to the problem he has posed in his own study. See Anderson, From analysis to synthesis, p. 31.

[29]Cassuto, Genesis, p. 34.