©Copyright 2018 GEOSCIENCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE

11060 Campus Street • Loma Linda, California 92350 • 909-558-4548

The Paradigm of Naturalism, Compared with a Viable Alternative: A Scientific Philosophy for the Study of Origins

by

Leonard R. Brand

Department of Natural Sciences

Loma Linda University

WHAT THIS ARTICLE IS ABOUT

As Thomas Kuhn (1970) pointed out, when a new paradigm is suggested there will at first be only a few persons who think that it is worthwhile. The paradigm's chance of success depends on the few individuals who demonstrate that they can do effective research under it. I propose that there are many similarities between Kuhn's general concept of scientific revolutions and specific application to the discussion of naturalism (science that will accept only hypotheses which do not imply a Designer) and interventionism (a paradigm that recognizes God's activity in history). The naturalistic paradigm has successfully guided science for a long time. Another paradigm based on informed intervention and catastrophist geology is now being applied as a guide in selected cases of field and laboratory research. There is evidence that in these cases the newer paradigm is successful. Consequently, it is beginning to be developed as a competing paradigm.

This article proposes that with careful analysis of the issues, we can show that interventionism is a valid approach to scientific investigation. There is a constructive way to relate science and faith so that each benefits the other, without inappropriate interference between them. When this method is used, it contributes to an improved understanding of earth and biological history.

For nearly nineteen hundred years most of the Christian world without question accepted the creation account in the book of Genesis as literal history. Charles Darwin and his supporters broke down this broad acceptance in only a few decades. Today the creation story may be credited with having some spiritual value, but to many people macroevolution is the only valid account for the origin of living things. Why did Darwin's theory have such an impact? Has it made the Christian's belief in a Master-Designer untenable? Or have some factors been overlooked? The following pages outline an approach to these and similar questions that affirms the integrity of the scientific process while maintaining a context of faith.

To understand the impact of Darwin's theory of evolution, we must first recognize that it has been very successful in doing what a good scientific theory does. Some years ago an article was published entitled "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution" (Dobzhansky 1973). That article illustrates the scientific community's confidence in the evolution theory and the extent to which this theory has been successful in organizing and explaining a broad range of biological data. An effective scientific theory will have the following characteristics:

- Organizes and explains previously isolated facts

- Suggests new experiments to be done; stimulating scientific progress

- Is testable can potentially be disproved if it is not correct

- Is based on repeatable experiments

- Predicts the outcome of untried experiments, thus increasing confidence in the accuracy of the theory.

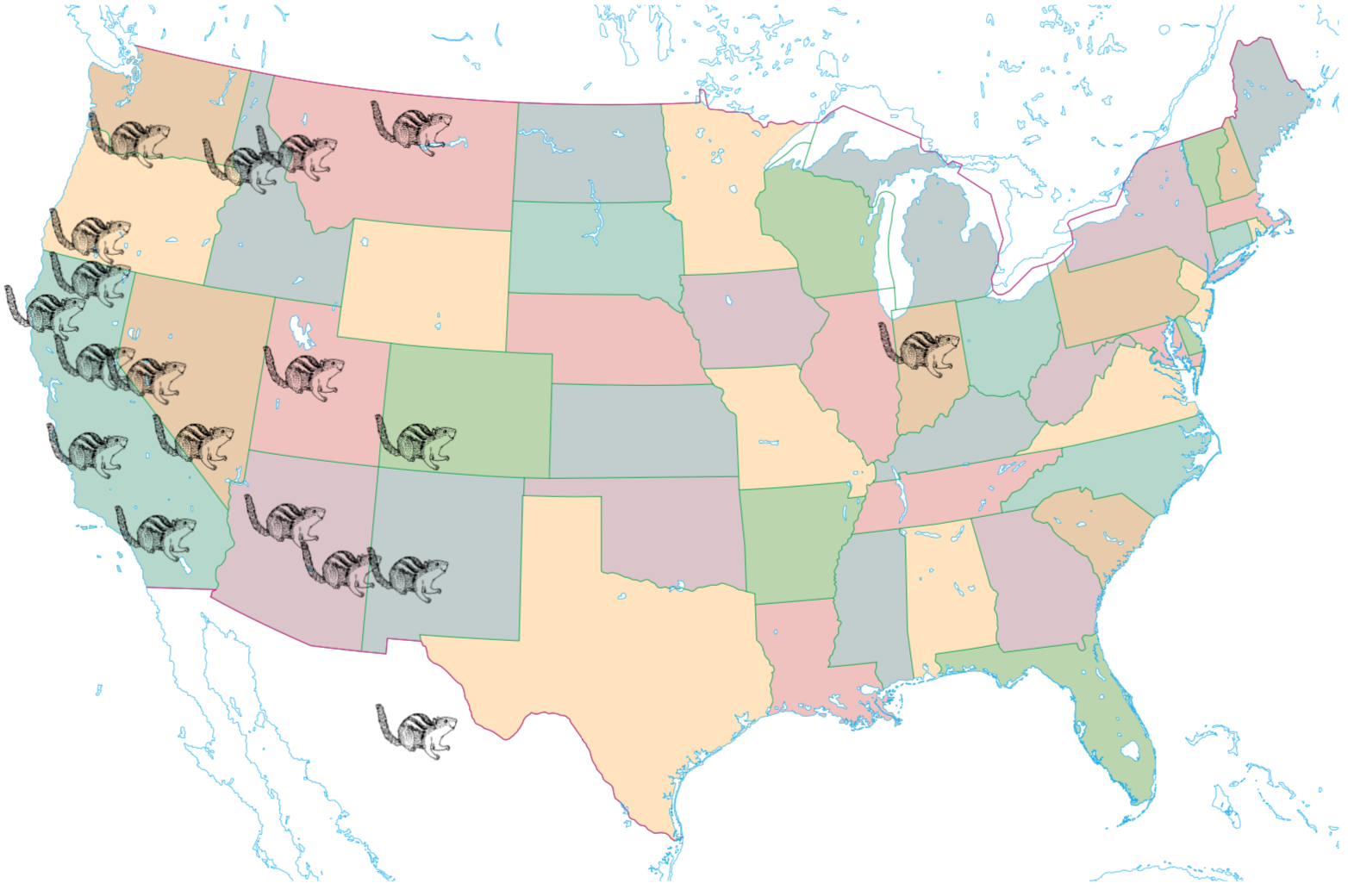

Chipmunks provide an example of the success of the evolution theory in the study of microevolution and speciation. Only one species of chipmunk, Tamias striatus, lives in the eastern half of the United States, but the western states have 21 species of chipmunks (Figure 1). Why are there so many species in the west but only one in the east? The evolution theory provides an answer. The west has a great variety of habitats suitable for chipmunks: dense brush, semidesert Pinyon Pine forests, Yellow Pine forests, high altitude Lodgepole Pine forests, etc. Many natural barriers of unsuitable habitat such as deserts or grassy plains separated small populations of chipmunks in isolated geographic pockets. As each isolated population became adapted to its habitat, some populations became different species through the action of natural selection. However, in the eastern United States the original forest environment was relatively uniform in relation to the needs of chipmunks, and there were few natural barriers adequate to isolate small populations of chipmunks, and thus to produce new species.

Microevolution not only provides explanations for the origin of new species and adaptations to new environments; it also has been highly effective in suggesting experiments to test these explanations. In many cases the theory successfully predicts the outcome of the experiments, often enough to give scientists great confidence in the theory of evolution. These are fundamental reasons why the theory is so widely accepted by the scientific community.

The history of science shows that even very successful theories sometimes need improvement or replacement, so it is always appropriate to continue examining the foundations of evolution theory, asking hard questions. Are all parts of the theory equally well supported? Have we overlooked or underestimated some important lines of evidence? Are there aspects of our logic that need to be improved? This critical analysis could benefit both science and religion if it is appropriately conducted. We must be honest with the data and with the uncertainties in the data, and careful to distinguish between data and interpretation. We must approach the task with humility and open-mindedness, and treat each other with respect, even if we disagree on fundamental issues.

In discussing these issues I will often use the term interventionism, rather than creationism, because it is a broader term it includes the possibility of divine intervention in geological history as well as in the creation. The paradigm of interventionism as presented here also proposes alternative interpretations in such things as rates of change in living organisms and in geological processes.

The general theory of evolution is based on the philosophy of naturalism (everything can be explained without reference to God), with its unwillingness to consider any hypotheses that involve divine intervention in the history of the universe. Is it possible that an alternative philosophy which accepts the possibility of divine intervention (interventionism) could also be successful in guiding scientific research?

Many diverse areas of science today build on the common underlying paradigm of naturalism (or materialism). People in medieval times were quite mystical in their thinking, and commonly appealed to the supernatural to explain things they did not understand. As understanding of nature improved, many of these mysterious phenomena became understood. This led scholars to shift toward the philosophical position of naturalism, which attempts to explain everything in nature through known natural laws. That is where science is today; it will only accept hypotheses that do not imply any divine action in earth history (Johnson 1991). This philosophy is a key element for understanding the relationship between informed intervention and science. In a discussion on the issue of teaching creation in the public schools, I heard a prominent scientist state that "even if creation was right I would have to deny it to be a scientist." To understand why a reputable scientist would make such a statement, it is necessary to understand the role of naturalism in science. Naturalism has become part of the definition of science:

If there is one rule, one criterion that makes an idea scientific, it is that it must invoke naturalistic explanations for phenomena, and those explanations must be testable solely by the criteria of our five senses (Eldredge 1982, emphasis in original).

Science cannot do experiments to test the supernatural. This concept is clear enough and is accepted by interventionists, but science has gone a step further and decided that it will accept only theories which do not imply or require any supernatural activity at any time in history.

What basis is there for this concept? When we observe the world around us we see that predictable natural law is in effect. Modern science has convinced most of us that normally God does not cause unexpected events to occur in the universe. The data are consistent with the proposal that He has established a set of laws, and the universe operates according to these laws. Consequently a scientist, including one who believes in God as Creator, can function on a day-to-day basis without referring to supernatural activity; and science has achieved much success by following this approach. However, some scientists acknowledge that God could have acted in history in ways which we would call miracles, such as creating the first living organisms. Science cannot test the concept of an informed intervention in history, but it should not reject a theory just because it implies an event that is outside our testable hypotheses.

From the naturalistic point of view, the idea that one who believes in informed intervention (an interventionist) can also be a scientist seems to be a contradiction. How can informed intervention, which by definition involves supernatural phenomena, be scientific, since science by definition excludes God's intervention? Can this seeming contradiction be resolved? We have discussed the characteristics of a good theory, and we have seen that evolution theory has these characteristics. Can there be any type of informed intervention theory that also has the same characteristics? I believe the answer is yes.

It is often implied that because interventionism originates from religion, it is for that reason unscientific. Does the source of a theory affect its validity? No! A theory is not scientific or unscientific because of its origin; it is scientifically useful if it can be tested. If it cannot be tested, it is outside the realm of science (even though it may be true).

TESTABLE AND UNTESTABLE HYPOTHESES

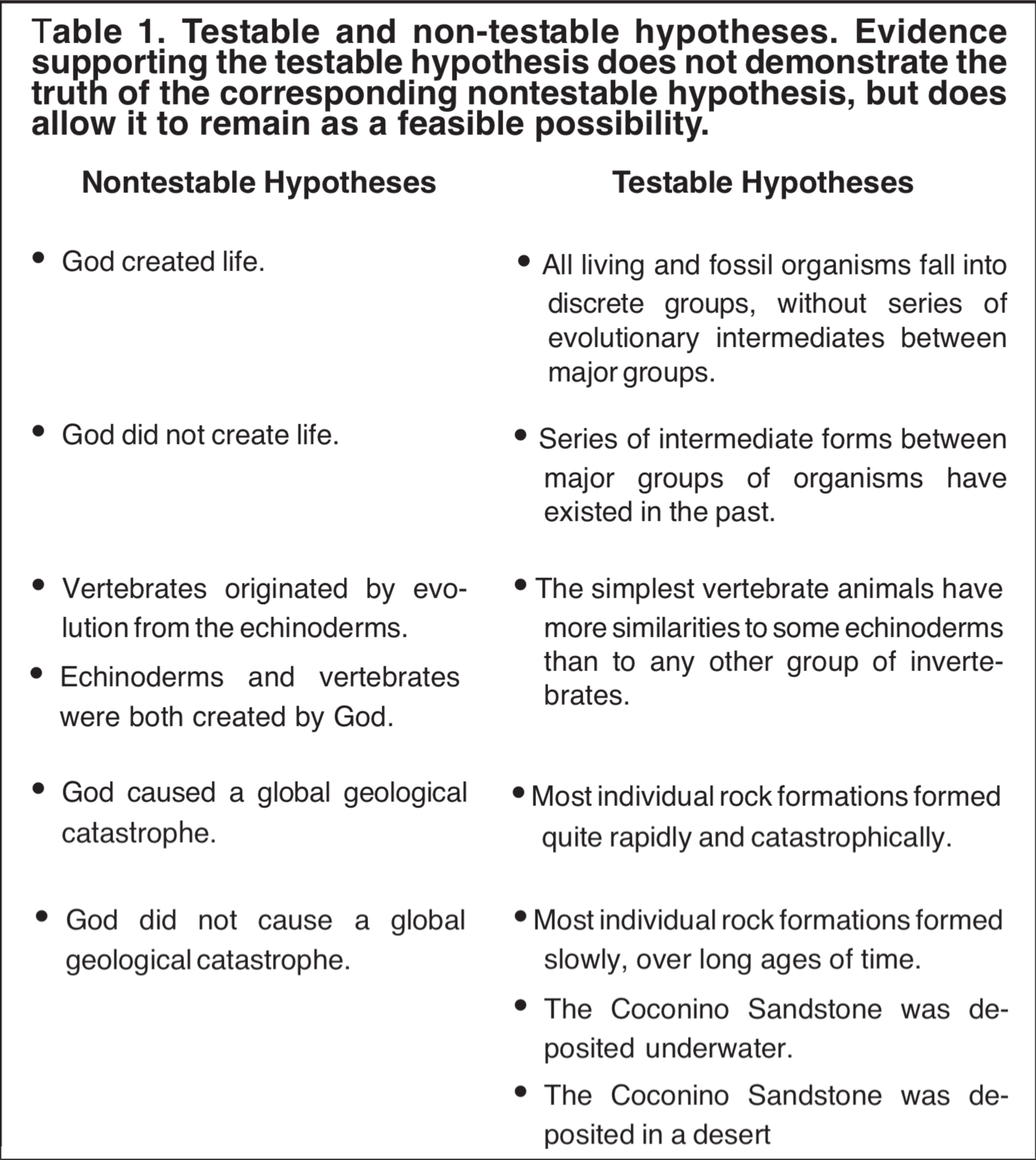

Some readers may conclude that the above explanation eliminates interventionism from the realm of science, since the hypothesis of informed intervention cannot be tested. Perhaps it is not that simple, since there are testable aspects and untestable features of both interventionism and naturalistic evolution. Scientists would generally agree that the hypothesis "God created life" (Table 1) cannot be tested by science. We cannot define an experiment or set of observations which would potentially falsify that hypothesis. This leaves us with the alternative hypothesis, "life was not created by God," which is more likely to be accepted as valid science.

In the light of our definition of a useful scientific theory as one that can be tested, can an experiment or set of observations be formulated which would potentially falsify the hypothesis "life was not created by God"? Be careful with your logic as you try to devise a test. A test, for example, which describes how a creator would design organisms, and then shows that organisms are not designed that way, is not valid. How would we know how a creator would or would not design life? The test must be more objective and independent of our opinions.

The concepts "God created life" and "God did not create life" are equally untestable. Science should either: 1) devise a valid experimental test for one or both of these hypotheses, or 2) not try to say that one is scientific and the other is not.

Even though both theistic and naturalistic paradigms include concepts that cannot be tested by science, it is possible to define hypotheses which are descriptions of results that should be discoverable in nature, if one of these nontestable hypotheses were true. The first requirement for making testable hypotheses is to leave out any consideration of whether a divine being or Designer was or was not involved. What is left are questions about objective things that may be found in the rocks or in living organisms. For example, if at least the basic groups of life forms were created, series of evolutionary intermediates between these groups are unlikely to be found, but if these groups were all the result of evolution it seems that a reasonable number of intermediate series would be found. If you are familiar with the evidence regarding this issue you already know that there is good news and bad news for both of these hypotheses. Someone who is looking for an easy falsification of either of the two basic hypotheses will be disappointed. The evidence is complex and our understanding of it is very incomplete; but in principle, science should be able ultimately to test between these two descriptive hypotheses.

I propose that scientifically useful (testable) theories like some of those listed in Table 1 can originate from religious concepts. We cannot directly test whether God involved Himself in earth history, but if He did involve Himself in ways described in the Bible (creation and world-wide geological catastrophe), these events should have left some evidence in the natural world. For example the evidence would include only limited evidence for evolutionary intermediates, but pervasive evidence for catastrophic geologic action. Moreover, the possible existence of such evidence can be investigated scientifically.

THE SUPERNATURAL AND THE LAWS OF NATURE

There is an important difference between saying: (a) "perhaps miracles have happened, but science cannot tell us if they have or not"; and saying: (b) "science denies that any miracles have ever happened, and will not accept any hypotheses that imply that miracles have happened." Consider for example the hypothesis "many phyla of organisms appeared on Earth suddenly, independent of each other." The response "this may have happened but science can't test this hypothesis" is quite different from "science can't consider this hypothesis because it implies a miraculous origin of life forms." In practice, science generally takes the second position, and will not allow for miracles even when they appear to be required by the nature of the evidence. This helps to explain the comment by the prominent scientist quoted on p 9 who stated that even if creation were correct, to be a scientist he would have to deny it. Evidently he sincerely believes that it is necessary to accept the naturalistic definition of science in order to be a good scientist. Is that the way it should be, or has the pendulum swung too far, and gone from one extreme (medieval pervasive supernaturalism) to another extreme (strict naturalism)? I respect the right of others to believe that it is necessary to accept this type of naturalism to be a scientist, but I will try to persuade you that strict naturalism is not the only paradigm that can lead to effective science.

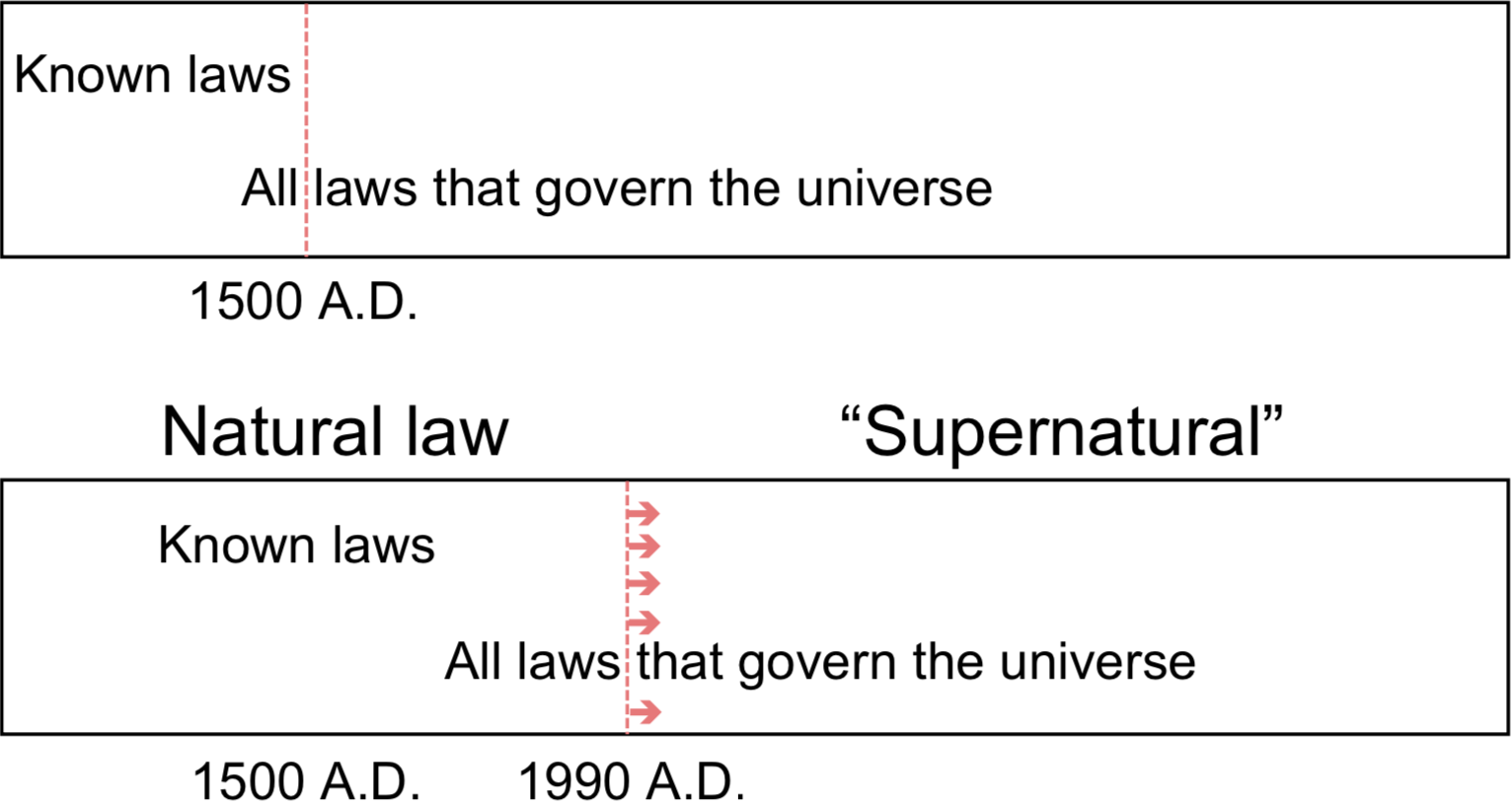

Are miracles really capricious magic, or is there another way to understand the supernatural? Imagine that God wrote down on microfiche all laws that govern the universe. In the year 1500 AD, for example, scientists knew a small percentage of these laws (Figure 2). Time moved on and we learned more of them, until by the late 1990s we knew a larger proportion of the laws, but there are still many that we have not discovered. Imagine that someone had invented a time machine that would allow us to interject a 16th century person into the 20th century. We take him into a supermarket, and the door opens by itself as we approach. We get into a car and turn a switch and the strange carriage roars and moves down the road. We then go home and flip a little lever on the wall and the lights come on. About that time the fellow might flee in terror at these "supernatural" manifestations. Why would he think of it that way? The simple difference between his thinking and ours is that he is not familiar with the laws governing the operation of cars, electricity, etc., or with the sources of energy that make our gadgets work. He thinks of these as supernatural, but in reality he just does not understand them.

Another aspect of this same issue can be explained with an example. If I hold a book in the air and drop it, the law of gravity specifies that it will fall to the floor. We can drop it a million times and the same action always occurs. However, since I am a mobile, reasoning being, I can decide to stick out my hand under the falling book, so that it does not fall to the floor. I have interjected an outside force into the system and changed the course of events, but I have not broken any laws. God could decide to interject an outside force into Earth's balanced geologic systems and change the course of events to bring on a catastrophe, without breaking any laws of the universe.

The portion of the laws of the universe that we understand we call natural law. The things that God can do that we do not understand, we call supernatural. To us they are indeed supernatural, since we do not understand them, and/or because we have no access to the source of power that God uses. To God all the laws of the universe are a unified whole. They do not limit Him, because He designed them to control the operation of the entire universe according to His plan. If this is true, someday He could explain to us how some of the laws that are currently beyond our understanding were involved in the performance of what we call miracles, such as instantly creating life or turning water to wine. Then we may say "now I see how You did it." We will still not have the power to do many things that God can do, but we will see that they are not magic or capricious acts, but are part of the law-bound whole that God understands and uses to accomplish His purposes. God may make use of certain processes described in those laws only during the process of creation, and not use them at other times. This concept implies that He understands it all, but we do not; He can make use of all possibilities, while we will never have the power to utilize some of them, even if we do eventually understand them. That is the difference between natural law and what we call supernatural.

This concept is fundamentally different from the "god of the gaps" that gave way in the face of modern science. The old "god of the gaps" existed because of the tendency to explain things that we couldn't understand (the "gaps" in our explanations) as resulting from the direct operation of God's power. When science searched out the answer to one of those gaps, God was not needed to solve that problem anymore, and consequently the more we learned, the less we needed God, or so it seemed. When William Harvey learned that the heart was a pump (a "machine" whose operation could be understood), and that the blood was not moved by the direct intervention of God, his new insight was not appreciated by some individuals, because it seemed to push God a little farther away.

In reality the logic in the "god of the gaps" concept was naive and implied that if we can understand how something works, God does not have any part in it. A further implication is that if God is involved in some process, that process does not function through nature's laws. That is no more defensible than to claim that since we understand how a computer works, there must not have been any intelligent beings involved in its origin. In contrast, I submit that God works according to the laws that He has established; that when we learn how the heart works we have not diminished God, we have just learned more about His laws and His magnificent inventions. Also, there is much about the universe and its laws that we do not know. It is unreasonable to assert that God cannot work outside the natural laws that are known to us, because the laws that we know are only a small part of the laws of the universe.

If this concept is sound, there is nothing unscientific about admitting the possibility of miracles. All it really requires is that we be willing to admit that there could be a Being in the universe powerful enough and knowledgeable enough to know and use all the laws that govern the universe. Even if we accept this, we understand that historical accounts of miracles are something that science cannot test, but it would not be unscientific to consider that such things could have happened. In some areas of science our research has progressed to the extent that the more we know, the more the data seem to imply that there was a Designer (Behe 1996).

BIASES FROM VARIOUS SOURCES

Could a person's religious perspective bias his or her interpretation of scientific data? It certainly can, and I could list a number of cases in which it is clear to me that this has happened. However, if we are not going to be superficial in our analysis of this problem we also have to ask another question: can a naturalistic philosophy bias a scientist's interpretation of data? I believe it certainly can. Our research will only answer questions that we are willing to ask, and naturalism allows only certain questions to be asked. Consider the difference between the following two questions:

Question 1: Which hypothesis is correct?

-

- Naturalistic hypothesis A (gradualistic evolution)

- Naturalistic hypothesis B (evolution by punctuated equilibria)

Question 2: Which hypothesis is correct?

-

- Naturalistic hypothesis A (gradualistic evolution)

- Naturalistic hypothesis B (evolution by punctuated equilibria)

- Major life forms did not arise by a naturalistic process (the implication of this answer creation by an intelligent Designer cannot be part of the testable hypothesis, just as the concept of naturalism cannot be a testable part of an evolutionary hypothesis)

Naturalism only allows question number one, and thus answer 2C is ruled out of scientific consideration by strictly a priori considerations. Naturalism has a powerful biasing influence in science, in steering scientific thinking and deciding, in many cases, what conclusions will be reached. This is not generally understood in scientific circles.

When the discipline of geology was taking form in the 18th and 19th centuries the geologists James Hutton (1795) and Charles Lyell (1830-1833) each wrote books in which they developed a paradigm of geology that rejected the catastrophism of their day, and replaced it with uniformitarian (always slow, gradual) processes over eons of time. Lyell's book was the more influential one for over a century, and constricted geology to a strictly gradualistic uniformitarian paradigm. Historical analysis of Lyell's work has produced the conclusion that the catastrophists in Lyell's day were the more unbiased scientists. Lyell took a culturally derived theory and imposed it upon the data (Gould 1984). Gould and others are not saying this because they agree with the biblical views of Lyell's colleagues; but it is apparent that those colleagues were more careful observers than Lyell, and they did not let their religious views twist their interpretation of data.

Various authors have stated that Lyell's strictly gradualistic version of uniformitarianism is not needed, or even has been bad for geology, because it has prevented geologists from considering any hypotheses that involved catastrophic interpretations of the data (Gould 1965, Krynine 1956, Valentine 1966). These authors are also not recommending a return to a Bible-based catastrophism. They are simply recognizing the evidence that many sedimentary deposits were catastrophic in nature. This recognition has brought the discipline of geology to accept the view called neocatastrophism, a naturalistic paradigm that explains the geologic record as developing over millions of years of evolutionary time, but with many catastrophic events that left their mark on the rocks (e.g., Ager 1981, Albritton 1989, Berggren & Van Couvering 1984, Huggett 1990). For a long time, Lyell's paradigm prevented geologists from recognizing the evidence for these catastrophic processes. Now that Lyell's bias has been recognized and abandoned, the philosophy of naturalism does not prevent recognition of catastrophic processes.

CONTROLLING BIAS IN SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

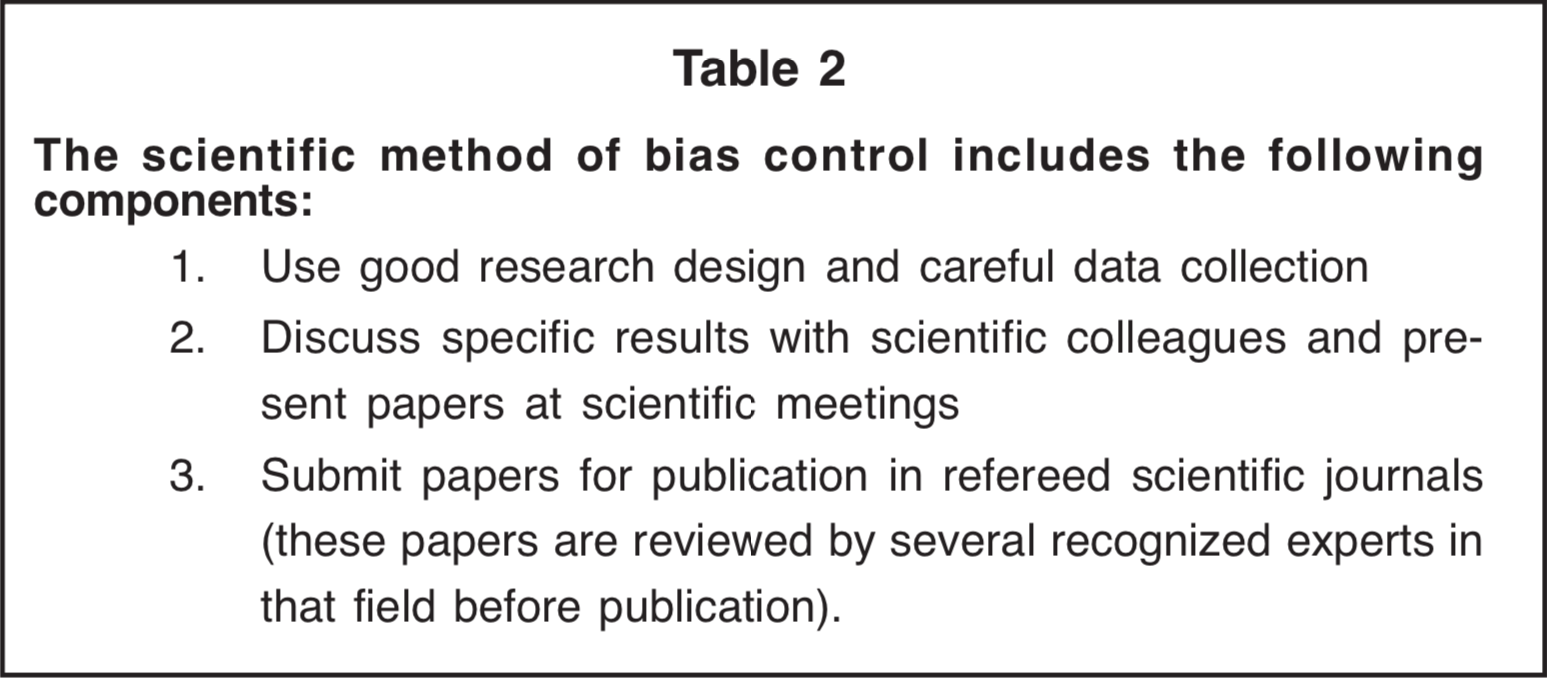

The problems that Lyell's gradualism has caused in geology suggest that religion is not the only factor which has the potential to bias one's interpretation of data. Such bias is not an informed intervention problem; it is a human problem that every one of us must be aware of and seek to overcome. Science has a method for correcting the effect of bias that can be effective for interventionists as well as others (Table 2).

This method is really the peer review system that helps to maintain quality in science; it is the critical discussion in Popper's (1963) scientific method. The peer review system cannot ultimately deal with philosophical questions like informed intervention, but any time we can use this philosophy (or any other) to help us define a hypothesis and collect data from rocks, fossils, or living organisms to test that hypothesis, the research data and their interpretation can be subjected to the process outlined above.

Bias is best controlled by critical interaction between scientists with varying views. Peer review did not soften Lyell's rigid geological gradualism for over a century. Why? Peer review could have functioned better if scientists with different views had continued to dialogue; if the catastrophists had not ceased to be influential. As it was, Lyell's gradualistic uniformitarianism was the only paradigm in use, with the result, until recent decades when accumulating data forced a review of Lyell's version of uniformitarianism, that the peer review system never addressed certain basic foundational questions about catastrophism.

I believe that science will benefit if it encourages active research by both scientists with a naturalistic orientation and those who accept the possibility of intervention. Both are searching for truth, and neither has anything to fear from the other if each is (1) actively engaged in quality research, (2) honest with the data, and (3) working not in isolation but as an active part of a scientific community in which there is active participation in professional meetings and peer-reviewed publication. There is no quality control quite like knowing that when a paper on our latest work is presented, there will be others, including some who disagree with us, who will be ready to point out the mistakes that we have overlooked! Also, scientists in each of these two groups are likely to recognize some types of data that the other might overlook.

IS THERE A VIABLE ALTERNATIVE TO NATURALISM?

Scientists who embrace interventionism need to be careful about criticizing scientists who make the naturalistic assumption, because there are reasons why they would want to take this approach. Science has been very successful since the adoption of naturalism, but before we deduce that this success demonstrates the truth of the naturalistic assumption, we need to look at the issues in more detail. The foundations of modern science were established by scientists who believed they were studying God's works. This belief did not prevent them from making significant pioneering discoveries. The development of modern scientific thinking after those early pioneers involved the adoption of several specific concepts:

- Living things and physical phenomena are like machines; they are mechanisms that can be studied and understood.

- On a day-to-day basis, natural processes are not dependent on the capricious whims of the spirits, or the operation of magic.

- The processes of nature follow predictable laws. By experiment and observation, we can learn what these laws are.

- Scientific hypotheses must be testable using only criteria accessible to our five senses.

- Change has occurred in organisms and in the physical universe neither are static. New species of animals and plants have arisen, and geologic structures change with time.

- Science will not consider the possibility of any intervention in the history or functioning of the universe by any higher power (naturalism).

Are items one to six equally essential for the success of science? The first concept is an assumption that is crucial for science, the second and third items are assumptions that expand on the first, and the fourth item is an operational assumption. I argue that these four concepts constitute the breakthrough that launched science on the road to its modern success. The fifth was an empirical observation and the recognition of this concept was also an important insight that opened up large vistas for research.

Some might say that naturalism follows inevitably if the first four concepts are true, but this is not necessarily correct logic. My car operates according to natural laws, and I find it interesting to study the natural processes that make it travel down the road. It is not necessary to assume a naturalistic origin for the car, in order to successfully understand its operation. The question of design, or informed intervention in the car's history only becomes an issue if I delve into the question of the car's origin. If I do, I will need to ask myself if I am willing to consider the possibility that in the origin of the car the laws of nature had some assistance from an intelligent designer. That may sound like a silly question, but it would not be trivial if we had no record of the origin of cars or similar machines. Of course analogies like this one have limits, and the car analogy breaks down because cars neither reproduce nor have a mechanism to evolve. It does still help to illustrate that as long as we accept the first four concepts, most of what science does would not be affected by whether or not we accept the sixth concept naturalism. Only when we study the beginnings of life, or the history of life and the universe, does it become necessary for us to decide what to do with the sixth concept naturalism.

The scientific paradigm that includes naturalism has been successful, but is it the only potentially successful paradigm? We will now compare naturalism with an alternative, which I will call partial naturalism (generally interchangeable with the term interventionism).

Naturalistic science will only accept hypotheses that are based on the uninterrupted operation of natural laws, as understood by science today, as the sole explanation of biological or geologic events and processes. But one clarification needs to be made at this point. Even naturalistic science does not properly deny that God exists or that divine intervention could have happened. It just doesn't use the scientific process to study such things. Science can only investigate natural processes, and that is why hypotheses that require or imply the existence of any type of divine intervention in earth history at any time are not acceptable to science. However, naturalism is often consciously or unconsciously interpreted to include claims such as "divine intervention is not true" or is "unscientific." In any case the result is a strong bias against interventionist concepts.

Partial naturalism assumes that on a day-to-day basis the processes of nature do follow natural laws. Living things and physical processes are like "machines" in the sense that we can figure out how they work, and what laws describe their structure and function. An interventionist scientist who subscribes to this paradigm can work and think like a naturalistic scientist, with one exception: he does not a priori rule out the possibility that an intelligent superior being has, on rare occasions, intervened in biological or geologic history, including the origin of life forms. It is also acknowledged that such interventions could have involved the use of laws of nature that are beyond the limits of current human knowledge.

Thaxton et al. (1984) have distinguished (a) operation science (study of recurring phenomena in the universe) from (b) origins science, concluding that intelligent intervention may have been involved in origins but should never be invoked in operation science. Science cannot test or define the nature of these possible interventions (that is in the realm of philosophy, not science), but science can recognize evidence that may point to the existence of "discontinuities" or unique events in history, and can examine their plausibility. The philosophy presented here is based on the conviction that if such discontinuities did occur, it is better to recognize their existence than to blindly ignore them.

There is a story of a man who was on his knees under a street light searching for something. A friend came by and asked what he was doing. He answered that he was looking for his keys. The friend helped search for some time, and then asked "are you sure you lost them here?" He answered "no, but the light is better here." Science can indeed see better when studying observable natural processes, but is that sufficient reason for denying that events of a different order could have occurred?

A comparison of the tenets of the two philosophies will further clarify the relationships between naturalism and interventionism. My understanding of informed interventionism can be partly defined with six concepts or assumptions paralleling those listed above. The first five are actually identical to those above. However, the sixth states that:

- There may have been, at certain times in history, informed intervention in geologic and biological history, especially in connection with origins. Hypotheses will not be shunned just because they imply the existence of such interventions.

This highlights the crucial difference between the thinking of a naturalistic scientist and an interventionist: the latter's unwillingness to set up definitions that eject the Designer out of the universe without a fair trial. In any attempt to draw out the potential similarities between informed interventionists and others, it is best to be candid about that difference. If a person is not willing to accept the interventionist version of assumption 6, they will no doubt reject much of the approach taken in the rest of this article. The interventionist assumption 6 does not specify what sort of intervention occurred, it only leaves open the door to ask seriously the second question in this example and a similar one given above:

Question 1: Which hypothesis is correct?

- Lyellian uniformitarianism, especially geologic gradualism

- Neocatastrophism: catastrophic events in a naturalistic framework

Question 2: Which hypothesis is correct?

- Lyellian uniformitarianism, especially geologic gradualism

- Neocatastrophism: catastrophic events in a naturalistic framework

- Catastrophism involving a global geologic catastrophe a relatively short time ago that produced a significant portion of the geologic column (with its implication of informed intervention in earth history).

A commitment to naturalism, on the other hand, does not allow question 2 to be asked because option 2c implies either (a), an interventionist origin of life forms, or (b), that there has not been enough time for an evolutionary origin of the life forms preserved in the geologic column.

EVALUATING THE TWO PARADIGMS

As individuals within each of these paradigms (naturalism and interventionism) evaluate the other paradigm, the tendency is to do exactly what Kuhn (1970, p 148) says will happen in such a situation. The two paradigms have differences in the rules that they follow (concept number 6, above), and as a result the practitioners of each approach end up talking past each other. The rules for doing science within naturalism (the six concepts above; naturalistic version) declare that partial naturalism/interventionism is, by definition (rule number 6), unscientific. In contrast, the interventionist considers this rule to be merely an untested hypothesis that could never be demonstrated by scientific data, and in fact has the potential to introduce serious biases into science. Lyell's geological gradualism restricted the range of hypotheses that could be considered, to the detriment of geology. Is it possible that naturalism has the same detrimental affect?

If the two groups sincerely wish to understand each other's thinking, each paradigm must be judged within its own rules. Followers of each paradigm must learn what it is like to think as those in the other paradigm think, without being judgmental (Thaxton et al. 1984, p 212). Only then are we prepared to make a fair evaluation of the internal consistency of each paradigm, and its success in dealing with the evidence.

In some cases informed interventionism is judged more by naturalism's rules than by the data. For example, the criticism has been made that rivers could not carve erosional features like the Grand Canyon in a few thousand years. Of course this criticism ignores the fact that the theory which puts all of this activity within a few thousand years does not rely on present-day rivers to do the erosion, but proposes that at one time there was much more catastrophic water flow. The same also works in reverse. If interventionists want to understand the paradigm of naturalistic evolution and be prepared to critique it meaningfully, they must evaluate it by its own rules before trying to compare it with the interventionist paradigm.

If we admit the possibility of divine intervention in history, it may seem to imply that earth history will be non-understandable and capricious not amenable to scientific investigation. This is where it is important to evaluate the paradigm's internal consistency, using its own rules. It will not be fair to evaluate this possibility using only the rules of naturalistic science. The fact is that if interventionism builds on the conviction that the Bible is a reliable communication from the Designer, it has a consistent and meaningful answer to this question. The God who intervened in history has taken the trouble to tell us about unusual events which might confuse us in our study of history if we did not know about them.

Imagine a large dam built across a canyon, backing up a lake several times larger than Lake Powell. One day the dam gives way, and the enormous rush of water erodes away the remaining traces of the dam. As the water cascades through the valleys downstream, it also erodes them into canyons many times larger than their original size. With time all human memory of the dam and its destruction is lost. One ancient book tells the story, but there is argument over the book's authenticity.

A geologist studying the canyons along the river rejects the validity of the old book and concludes that there is no natural process that could produce a flood so massive that it could account for the formation of the canyons in a relatively short time. He measures the flow of the river and the amount of sediment that it is carrying away, and calculates how long it took for the present river to carve the canyons. In time additional data point to catastrophic processes in the canyons, but he concludes that the indicated catastrophes were isolated floods with long time periods between them.

Another geologist is willing to seriously consider that the book may be reliable, and he decides that if it is correct, the insights in the book will help to keep him from misinterpreting the data. Without the book and its story of such a unique event, so different from even the natural catastrophes that are part of our modern analogues, it may be difficult or impossible for a scientist to have hope of even being able to think of the correct hypothesis for the origin of the canyons. Even more serious, he would not be aware of the problem.

If the book is correct it provides a logically consistent working hypothesis: the flood was the consequence of an unusual event, which someone told us about, and this knowledge gives us a trustworthy beginning point for developing specific hypotheses about the erosion processes.

The central issue is our willingness to seriously consider that the book might give a correct account. If there are those who think that it does, and they conduct themselves as careful researchers, I suggest that science will be benefited more if it maintains a friendly dialogue with these scientists, rather than defining them out of the dialogue.

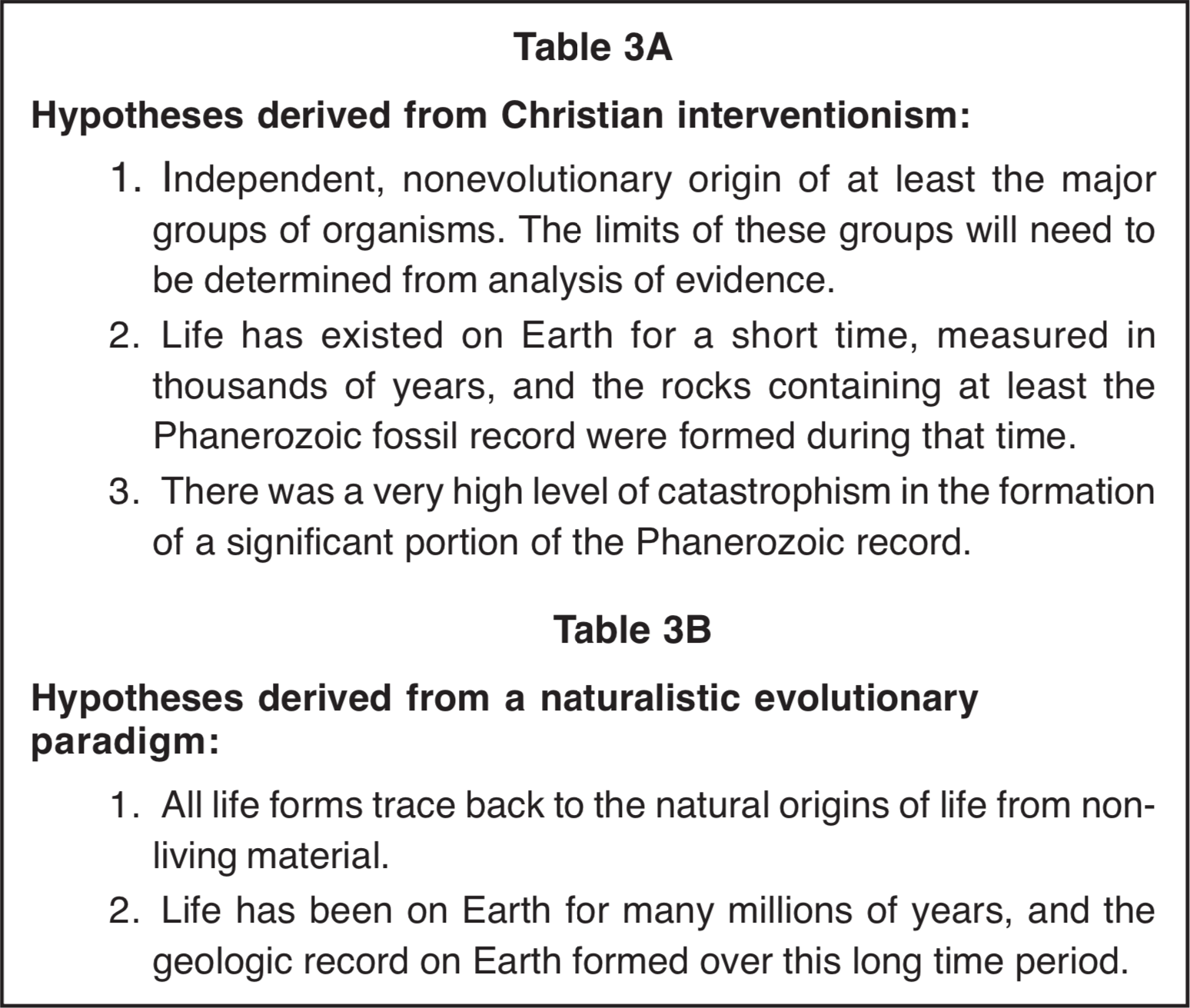

Interventionism can take many forms. The version presented in this essay concludes that the "old book" is a reality: the Designer has communicated to us, and there is evidence that the communication is reliable and describes the actual history of life on Earth. This communication is brief and leaves many unanswered questions, but if it is a reliable account, the most productive approach will be to take seriously the concepts it presents and see what insights they can give us in our research. Statements from the book cannot be used as evidence in science; but if those statements are true, it should be possible to use some of them as a basis for defining hypotheses that lead to productive field research. Several very general hypotheses that follow from this approach are listed in Table 3A, contrasted with parallel hypotheses based on a naturalistic evolutionary paradigm (Table 3B). Of course it must be remembered that the "old book" also contains much material that cannot be addressed from a scientific perspective.

RESEARCH UNDER THE PHILOSOPHY OF INTERVENTIONISM

My experience indicates to me that interventionism, as defined above, is an effective framework for doing science. Below are several specific examples of research that has been done under this interventionist philosophy, with resulting publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

1. Yellowstone Fossil Forests

In and adjacent to Yellowstone National Park, volcanic deposits contain a series of fossil forests, one above another, containing upright stumps that appear to be in their original position of growth. If this series of forests, containing some very large trees, grew in their current position, one forest after another, a very long time would be required for its accumulation. Interventionists began studying these forests to determine if there was an equally valid, alternative interpretation. This research has led to the development of the hypothesis that the fossil trees did not grow in situ (where they now are), but were transported to that location together with the sediments. Several lines of research, published in professional journals, now lend support to this hypothesis (Chadwick & Yamamoto 1984; Coffin 1976, 1983a, 1983b, 1987).

2. Coconino Sandstone Trackway Research

The Coconino Sandstone is generally considered to be formed from a series of desert dunes. The only fossils it contains are trackways of either amphibians or reptiles. When I began a study of the fossil vertebrate trackways in this formation I had doubts about the desert dune origin of the tracks, initially for philosophical reasons, and set out to evaluate alternative hypotheses for formation of the tracks. So far the data from study of the tracks support the hypothesis that the fossil tracks were made underwater (Brand 1979, 1992; Brand & Tang 1991). Whether future research will continue to support this hypothesis remains to be seen.

3. The history and status of white-footed mice (genus Peromyscus) on several islands in the Gulf of California

Alternative hypotheses for the status of these mice were that (1) the island mice were a separate species that had arisen from related mice on the mainland, Peromyscus eremicus, or (2) the island mice were still the same species as the mainland mice. In this case interventionist theory does not favor, a priori, one over the other. The evidence supported the conclusion that the island mice had become a separate species, apparently in response to isolation on the islands (Brand & Ryckman 1969). This and a number of similar studies demonstrate that an interventionist philosophy can be an effective stimulus for research on evolutionary processes without assuming that major groups of organisms arose by the process of evolution.

4. Precambrian Pollen in the Grand Canyon

Some interventionists have contended that Precambrian rocks in the Grand Canyon contain fossilized Angiosperm (flowering plant) pollen, and that this is evidence against evolution (Angiosperm plants presumably did not evolve until long after the Precambrian). A claim as significant as this should be independently verified to be sure of its authenticity. Another scientist repeated the research, and his data indicated that these rocks do not contain fossil Angiosperm pollen. The original claim apparently resulted from contamination of the samples by modern pollen (Chadwick 1981).

5. Human Tracks in Cretaceous Rocks

It has been widely claimed by some interventionists that Cretaceous limestone by the Paluxy River in Texas contains fossil human tracks in association with dinosaur tracks. As with the Precambrian pollen, such a significant claim should not be accepted without extensive careful study. The more significant the implications of the supposed evidence, the more rigorously it should be examined before proclaiming it as evidence for or against intervention or evolution. A restudy of the Paluxy River tracks convinced a number of us that they are not human (Neufeld 1975).

6. Other fields

In the medical sciences and in areas of biology, chemistry, and physics that do not deal with evolution or history, a number of interventionists are doing high-quality scientific research. Their interventionist philosophy does not in any way hinder them from effectively using the scientific process in their study of the workings of the natural world.

One danger that we must avoid at all cost is the very human tendency to think that because we believe that the Bible contains special insights, whatever ideas we develop based on this book are automatically right. George McCready Price (1906, 1923) provided an example of this problem. Even though the Bible says nothing about the ice age or the "out of order fossils," Price could not accept the possibility that his way of explaining the evidence pertaining to these might be wrong.

Research under the paradigm of interventionism (like other research) does not automatically lead to correct conclusions, but it begins a search in a particular direction. After the search is begun, several different turns may be necessary before the theory satisfactorily explains the evidence and has predictive ability. Some examples follow.

1. Yellowstone Fossil Forests

Initial interventionist hypotheses were that the fossil trees were actually on the surface of a slope, and did not go back into the hills in a vertical series of layers, or that there really were not many layers of forests. Research falsified these hypotheses, but led to a productive scientific hypothesis that the fossils were transported with the sediments.

2. Order of Fossils in the Rocks

George McCready Price began with the hypothesis (although he did not necessarily see it as only a hypothesis) that there is not a predictable sequence of organisms in the fossil record, but that the organisms were buried in a random sequence during the flood. That hypothesis has been falsified, but the research involved in falsifying it led to another hypothesis ecological zonation (Clark 1946), which still needs much refinement before it will adequately explain the fossil record. Whether it will stand in modified form or be replaced by a different hypothesis remains to be seen.

3. Coconino Sandstone Trackway Research

My first hypothesis was that the vertebrate trackways in the Coconino Sandstone were formed in some type of wet sand environment (but not underwater), but the data did not support this hypothesis. Further study suggested that the fossil tracks were most likely made while the animals were completely underwater, and so far that hypothesis has strong support from continued study of the tracks.

Errors in the initial theory or assumptions do not, in the long run, prevent truth from emerging, although beginning with the correct assumptions speeds the process. If catastrophist geologists had continued, after Lyell's time, to successfully use their paradigm in research, their work would have provided an influence to counterbalance Lyell's rigid gradualism, and the turn to catastrophist interpretations could have occurred sooner.

A NEED FOR CAUTION

At this point we need to look at the other side of the coin. Even if catastrophist geologists use their theory effectively and make discoveries that others have overlooked, there will be limits to the scientific conclusions that can be drawn with this approach. Science cannot demonstrate whether God was or was not involved in influencing our geologic history. Even if research eventually demonstrates that the best explanation for the geologic column is rapid sedimentation of a major portion of the column in one short spurt of geologic activity, this would only make it reasonable to believe the flood story if our confidence in Scripture leads us to do so. It would not prove, scientifically, that God caused a flood.

WHY BOTHER?

We still must pursue the question: why bother to try using this novel approach? Maybe interventionism can be a basis for doing scientific research, but is there really a need for that paradigm? Geology did correct Lyell's mistake, apparently without any help from outside of naturalism; so why is informed intervention needed? There are many bright and successful scientists who are convinced that the theory of the evolution of life forms adequately explains the evidence, and there is no need for the informed intervention hypothesis. I can understand the rationale for their attitude, and I will defend their right to disagree with me. I also suggest that there are dimensions to these issues that often are overlooked, and that there are good reasons for taking seriously the possibility of informed intervention. It is not presented here because there is proof for it, or because it can currently answer all the questions; but because of a conviction that it has something important to offer for science as well as for religion. A clear discussion of the issues requires that we differentiate between several separate questions that are a part of the evaluation of interventionism vs. naturalism.

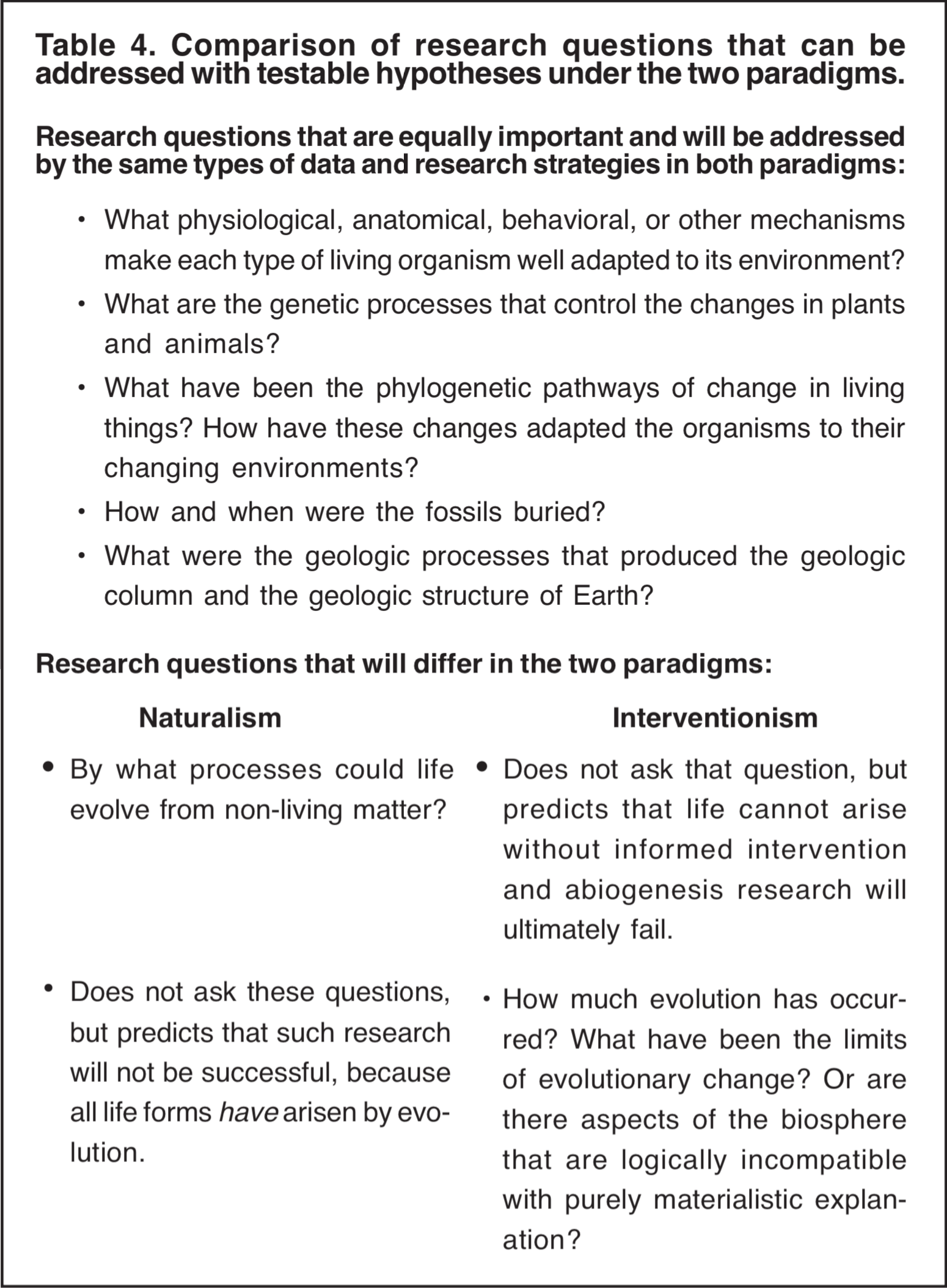

The progress of the last two centuries tells us that naturalism has resulted in scientific progress. Whether or not we agree with the tenets of naturalism, it is unreasonable to say that naturalism is not an effective paradigm. For reasons given in this article, I argue that interventionism can also result in effective science. The demonstration of that potential is just beginning, but interventionism can produce good science. Many of the specific questions that can be addressed with testable hypotheses are essentially the same under the two paradigms, but some will differ, as illustrated by the examples in Table 4.

Can the concepts of naturalism or interventionism be tested? The answer in both cases is no. Both naturalism and interventionism are based on non-testable assumptions, and the decision between them is based on a philosophical choice. Do either naturalistic evolution or informed intervention provide a sufficiently convincing explanation for the evidence? The answer to this question would take much more space than is available in this article, but for now I will suggest that at this time naturalism has better answers for some data, and interventionism does better at interpreting other data. Some will no doubt say that naturalism is the clear winner in effectively interpreting the data. There are reasons for considering that answer to be premature. Ultimately, with much more data available the evidence should point more clearly to one of these paradigms as being much more successful at explaining the evidence. The adherents of each paradigm will have their own prediction as to which way the data will ultimately point. Which paradigm has more promise for effectively guiding scientific research in the future? The answer to this question is largely based on philosophy, on a prediction determined by what we each believe is the true history of life on Earth.

At this point we can return to a statement made earlier, that science should either devise an experimental test for one or both of the concepts "God created life" and "God did not create life," or not try to say that one approach is scientific and the other is not. Is that analysis fair? From what I have read and heard of the arguments between these two paradigms, I have to say that it is a fair analysis. Attempts by some creationists to make naturalistic scientists look foolish are unfortunate and unrealistic. Those scientists are doing productive science. However, it is also true that if proponents of naturalism wish to say that interventionism cannot be science, they need to devise credible scientific tests with the potential to falsify one or both of the hypotheses: "God created life" and "God did not create life."

It could be argued that naturalism, properly defined, does not make either of the statements in these hypotheses. It only recognizes that science cannot address either hypothesis and only asks how life could have originated if it arose by purely mechanical means. If it was clear that most scientists understand naturalism this way, and that most of them are comfortable with the thought that it is also intellectually credible to approach science from within a non-naturalistic philosophy, then this essay would not be necessary. However, in practice naturalism does not seem to be generally interpreted that way. It is commonly considered intellectually unacceptable to consider seriously the hypothesis "God created life." But in the absence of experimental tests for these and similar hypotheses, the attempt to make interventionism, as defined here, outside of the realm of science is based strictly on an arbitrary, a priori definition.

To the question "why bother?" my answer is that interventionists are not asking anyone to bother trying this approach if they do not see a reason to, but some of us actually believe that interventionist science will ultimately be more successful, because we believe that its basic tenets are closer to reality than is naturalism. At present this belief is based on a philosophical choice, and could be criticized for being a religious choice; and so it is. But the only religion worth having is a religion based on truth. If we believe our religion is truth, and that it offers insights into earth history, we would be missing something important if we do not use it for generating testable scientific hypotheses.

As Thomas Kuhn (1970) pointed out, when a new paradigm is suggested there will at first be only a few persons who think that it is worthwhile. The paradigm's chance of success depends on those few people demonstrating that they can do effective research under it. I propose that there are many similarities between Kuhn's general concept of scientific revolutions and specific application to the naturalism/interventionism debate. The naturalistic paradigm has successfully guided science for a long time. The much newer paradigm based on informed intervention and catastrophist geology is being applied as a guide in selected cases of field and laboratory research. There is evidence that in these cases it is successful and is beginning to be developed as a competing paradigm.

Someone may respond that actually there was a revolution back in Darwin's day, when creationism was rejected. I suggest a different point of view: that the theories of evolution and uniformitarian geology developed in fields which up to that time lacked any coherent theories, and were in a preparadigm state. The first cohesive paradigms in these fields developed in an intellectual atmosphere strongly favoring naturalism. Consequently they were purely naturalistic. We now can look carefully at the data that have accumulated, see the strengths and weaknesses in the established paradigms, and propose competing paradigms. Research done under this new interventionist paradigm is beginning to have an influence on the body of scientific evidence available in certain specific areas where such research has been concentrated.

This discussion is not meant to imply that the scientific community is on the verge of a paradigm shift to interventionism. The relationship between the two origins paradigms has some interesting similarities to other paradigm competitions, but there are also important differences. The shift to plate tectonics (the theory that explains drifting continents), for example, did not require anyone to reevaluate the scientific method. Plate tectonics and the previous paradigm were both compatible with a naturalistic, evolutionary explanation of earth history, and consequently there was no strong barrier to acceptance of the plate tectonics concept after a few key discoveries threw the weight of evidence in its favor. In contrast, interventionism redefines the limits of the scientific endeavor, and raises fundamental questions about the meaning of human life and our relationship to a higher power. Also, since the evidence needed to resolve the intervention/naturalistic-evolution debate is orders of magnitude more complex than in other recent paradigm competitions, it is unrealistic to think that a few key discoveries will win over the scientific community to an interventionist position. A peaceful coexistence between the two philosophies is a more practical goal.

WHAT SHOULD INTERVENTIONISTS BE DOING?

In published articles on the discussion over creationism a key point that is often brought up is that creationists, no matter what they may say, are not scientists they are not doing research. Eldredge (1982) states that no creationist "has contributed a single article to any reputable scientific journal." Actually a number of interventionists are active in research, but this is not widely known. In an atmosphere of such unfriendly debate between the two views, interventionists who are scientists will not often make their philosophical views known.

I believe the approach that is beneficial in the long run is for interventionists to conduct themselves as genuine scientists and get actively involved in research. It is important to try to develop an alternative paradigm, a successful alternative way of interpreting the data, rather than only poking holes in someone else's theory. If interventionist efforts center around disproving the prevailing evolutionary paradigm, the response will be: what do you have to offer that is better (i.e., a more successful guide for scientific research)? Interventionists should work on developing an alternative paradigm, rather than focus only on efforts to disprove evolution.

Ideally, a person's philosophy shouldn't matter as long as he or she does good science. That is the ideal, but there is a common perception that interventionists, by definition, cannot be objective scientists. This perception can only change as interventionists diligently pursue careful, quality research. On the other side of the coin many interventionists accuse "those evolutionists" of lacking any objectivity (or worse). Why do we do this to each other? We don't have to agree on everything to value each other's work. The ultimate tests of any scientist are their honesty in dealing with the data and quality of research, not personal philosophy. For the scientific community simply to judge a person on his or her honesty and effectiveness in research should be enough. This would eliminate many battles over philosophical issues.

REFERENCES

Ager DV. 1981. The nature of the stratigraphical record. 2nd ed. NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Albritton CC, Jr. 1989. Catastrophic episodes in earth history. NY: Chapman and Hall.

Behe MJ. 1996. Darwin's black box: the biochemical challenge to evolution. NY: The Free Press.

Berggren WA, Van Couvering JA, editors. 1984. Catastrophes and earth history: the new uniformitarianism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brand LR. 1979. Field and laboratory studies on the Coconino Sandstone (Permian) vertebrate footprints and their paleoecological implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 28:25-38.

Brand LR. 1992. Reply: fossil vertebrate footprints in the Coconino Sandstone (Permian) of northern Arizona: evidence for underwater origin. Geology 20:668-670.

Brand LR, Ryckman RE. 1969. Biosysternatics of Peromyscus eremicus, P. guardia, and P. interparietalis. Journal of Mammalogy 50:501-513.

Brand LR, Tang T. 1991. Fossil vertebrate footprints in the Coconino Sandstone (Permian) of northern Arizona: evidence for underwater origin. Geology 19:1201-1204.

Chadwick AV. 1981. Precambrian pollen in the Grand Canyon a reexamination. Origins 8:7-12.

Chadwick AV, Yamamoto T. 1984. A paleoecological analysis of the petrified trees in the Specimen Creek area of Yellowstone National Park, Montana, USA. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 45:39-48.

Clark HW. 1946. The new diluvialism. Angwin, CA: Science Publications.

Coffin HG. 1976. Orientation of trees in the Yellowstone petrified forests. Journal of Paleontology 50:539-543.

Coffin HG. 1983a. Erect floating stumps in Spirit Lake, Washington. Geology 11:298-299.

Coffin HG. 1983b. Erect floating stumps in Spirit Lake, Washington; reply. Geology 11:734.

Coffin HG. 1987. Sonar and scuba survey of a submerged allochthonous "forest" in Spirit Lake, Washington. Palaios 2:178-180.

Dobzhansky T. 1973. Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. The American Biology Teacher 35:125-129.

Eldredge N. 1982. The monkey business: a scientist looks at creationism. NY: Pocket Books (Washington Square Press).

Gould SJ. 1965. Is uniformitarianism necessary? American Journal of Science 263:223-228.

Gould SJ. 1984. Lyell's vision and rhetoric. In: Berggren WA, Van Couvering JA, editors. Catastrophes and Earth History: The New Uniformitarianism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Huggett R. 1990. Catastrophism: systems of earth history. NY: Edward Arnold.

Hutton J. 1795. Theory of the earth with proofs and illustrations. 2 vols. Edinburgh: William Creech. (Reprinted 1959. Weinheim: H. R. Engelmann (J. Cramer) and Wheldon and Wesley, Ltd.)

Johnson PE. 1991. Darwin on trial. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Krynine PD. 1956. Uniformitarianism is a dangerous doctrine. Journal of Paleontology 30:1003-1004.

Kuhn TS. 1970. The structure of scientific revolutions. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lyell C. 1830-1833. Principles of geology, being an attempt to explain the former changes of the earth's surface, by reference to causes now in operation. 3 vols. London: John Murray. (1892. Principles of geology, or the modern changes of the earth and its inhabitants considered as illustrative of geology. 11th ed. 2 vols. NY: D. Appleton and Co.)

Neufeld B. 1975. Dinosaur tracks and giant men. Origins 2:64-76.

Popper KR. 1963. Science: problems, aims, responsibilities. Federation Proceedings 22:961-972.

Price GM. 1906. Illogical geology. Los Angeles: The Modern Heretic Co.

Price GM. 1923. The new geology. Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Publ. Assn.

Thaxton CB, Bradley WL, Olsen RL. 1984. The mystery of life's origin: reassessing current theories. NY: Philosophical Library.

Valentine JW. 1966. The present is the key to the present. Journal of Geological Education 14(2):59-60.