©Copyright 2018 GEOSCIENCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE

11060 Campus Street • Loma Linda, California 92350 • 909-558-4548

The Scientific Method

All scientific endeavors begin with a question. The questions we ask are typically influenced by our worldview. For example, a Darwinist may ask, “How did the appendix evolve?” While a Bible-believer might ask, “What was the appendix created for?” The questions we ask determine the answers we seek. Imagine being a scientist who wonders; “What does the appendix do?” How would you proceed?

Discovering what data are already available about the appendix would be a good start, so from books you learn the appendix is about the size of a finger and dangles off the large intestine. Sometimes it becomes inflamed and, if it is not removed, can kill a person. However, if the appendix is removed, people can still live healthy lives.

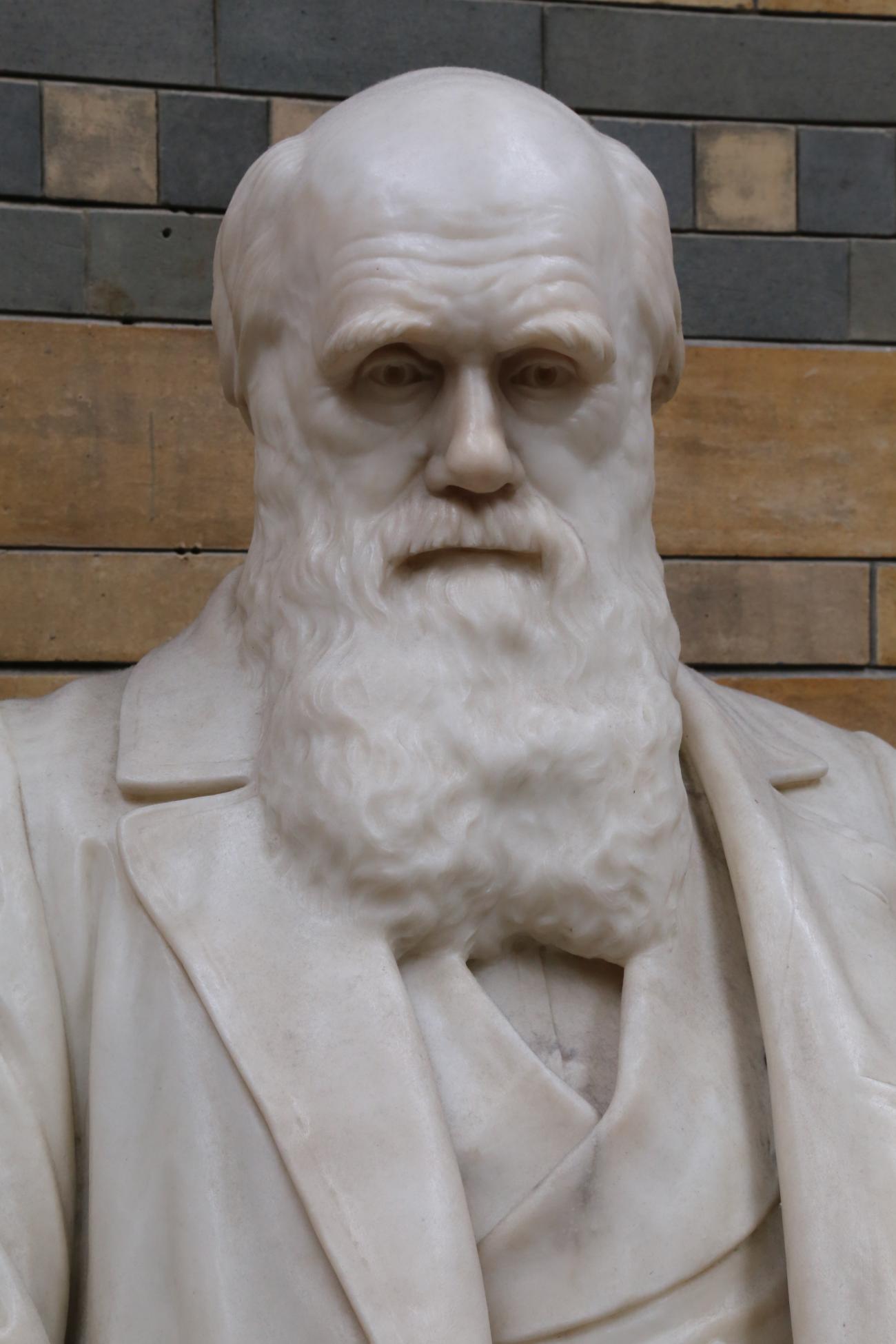

Charles Darwin looked at this evidence and interpreted it this way:

“That this appendage [the appendix] is a rudiment, we may infer from its small size, and from the evidence … of its variability in man. … Not only is it useless, but it is sometimes the cause of death, …”[1]

A logical inference from data, like this, is commonly called a “theory.” Theories are one of four components of the scientific method:

- Data – observations that are relevant to the question being asked

- Theory – An explanation of data addressing the initial question

- Hypotheses – logical deductions from theories. These must be true if a the theory is true

- Experiment – an empirical test of a hypothesis. This generates more data (and frequently more questions)

Interpreting organs like the appendix as rudiments or vestiges of once useful organs inherited from our ancestors may work within a Darwinian evolutionary framework, but not very well.

The problem is that from a logical perspective, Darwin’s interpretation of the evidence is unsatisfying. It can be construed as relying on an argument from ignorance: “I don’t know what this does, so it must do nothing.” If the appendix does nothing and sometimes kills people, natural selection should have eliminated it as it has, according to Darwinian thinking, in other organisms such as squirrels and chinchillas [2]

This assumption may also work within a biblical framework, if it is assumed that Adam had a functional appendix and that function has been lost in modern humans. From a biblical perspective, why would God create an organ with the potential to kill humans unless it performs some important function? Both Darwinism and the biblical worldview offer unsatisfying explanations for a useless appendix. The theory that the appendix actually does something seems simpler, thus more likely to be true if Ockham’s razor is used.

A “hypothesis” is logically derived from a theory, although this term is loosely defined and can mean a hunch based on one or a few observations. In the sense I’m using “hypothesis” here, it basically says, “If theory X is true, then Y must be true.” To be scientific, a theory must generate testable hypotheses. The theory that the appendix is functionless generates testable hypotheses. For example, “If the appendix is functionless, then removing it should make no difference.” “Experiment” is simply another word for the kind of test that can be done based on this hypothesis. So the functionless appendix theory is definitely scientific, but that does not necessarily mean that it is true.

The kinds of hypotheses that a scientist comes up with may be strongly influenced by their worldview. For example, a Darwinist might hypothesize that if the appendix is functionless, then there should be a clear pattern of its evolution when “related” organisms are compared. In fact, this hypothesis has been tested and the “pattern” is not what would be expected. The presence and absence of the appendix in different mammal groups requires that it evolved and disappeared multiple times, hardly a simple clear pattern [2]

The Bible says that humans are “fearfully and wonderfully made” (Psalm 139:14), which seems at odds with the existence of functionless and dangerous organs. Someone who embraces the biblical worldview is probably going to have a problem with the functionless appendix theory, even if they lack a theory about what its function is. They are more likely to ask, “What does the appendix do?” Instead of having a clearly testable hypothesis, they may simply go and look at the appendix a little more closely before dismissing it as functionless.

The theory that the appendix functions to reboot gut bacteria is consistent with more data than the theory that it is functionless. But even good theories are commonly in tension with at least some observations. If the appendix is so important, why can it be removed without killing a person? The explanation lies in the fact that widespread appendix removal coincided with the rise of modern medicine and public health practices. Rates of acute diarrhea have declined due to better sewer systems and safe water supplies. In addition, antibiotics and other medicines have greatly helped in the treatment of some formerly common causes of diarrhea. Less diarrhea means less dependence on the appendix to reboot the gut.

Is the theory that the appendix reboots gut bacteria true? That is a hard question to answer. A good scientist will be a little skeptical no matter how well a theory appears to explain the relevant data. We can never have all the data and, even if we did, there may still be multiple logical theories that explain it. What if Ockham’s razor is wrong and a more complex explanation is actually the correct one? How can we be absolutely sure that another scientist has not become so carried away by their worldview that they only recorded data consistent with it, dismissing other data as irrelevant or unimportant?

There are many reasons a theory may be wrong, but generally a theory that is consistent with logic and data, not ignoring data that are in tension with it, is a valuable starting point in understanding nature. The scientific method is not a way of proving a theory true in the same way that postulates can be used in a geometric proof. It is a way of testing a theory by seeing if hypotheses derived from it hold up under testing with experiments, analyzing the logic and comparing it to new data. The objective is not to prove the theory true, it is to discover how robust the theory is and, if it fails in some way, to replace it with a new theory that better explains the data.

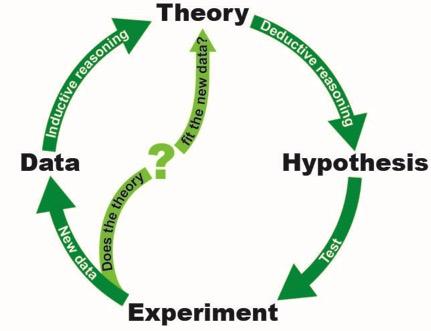

At this point the scientific method may seem a little muddled, imprecise and confusing. This is because in practice it can actually be that way. A simplified diagram of how the scientific method works can be found in the figure below. Reality is never quite this simple.

The scientific method uses inductive reasoning to generate theories that explain data. Deductive reasoning is used to generate testable hypotheses that must be true if a theory is true. When the hypothesis is tested, it may fit well with the new data generated, thus supporting the theory (but not proving it true). If the hypothesis is inconsistent with data, then the theory is inconsistent with data and needs to be modified in some way, or completely replaced with a new more comprehensive theory.

Timothy G. Standish, PhD

Senior Scientist, Geoscience Research Institute

Footnotes

[1]Charles R. Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex 2d edition. (London: John Murray, 1882), p 21.

[2] Smith HF, Fisher RE, Everett ML, Thomas AD, Bollinger RR, Parker W. 2009. Comparative anatomy and phylogenetic distribution of the mammalian cecal appendix. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 22(10):1984-99. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01809.x. Epub 2009 Aug 12).