©Copyright 2018 GEOSCIENCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE

11060 Campus Street • Loma Linda, California 92350 • 909-558-4548

This article was originally published as a chapter in the book “The Genesis Creation Account and Its Reverberations in the Old Testament."

INTRODUCTION

In this study, we seek to investigate the presence and significance of creation motifs and/or ideological elements found in Genesis 1 through 3 that may be present in the books of Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes. This is basically an intertextual study. We will explore the biblical text in its final form. We will also examine the possible influence of ancient Near Eastern creation accounts on the wisdom literature. Old Testament scholars generally recognize that wisdom thinking and theology are directly related to the topic of creation and that creation provides a coherent perspective from which to study it by integrating wisdom thinking into the theology of the Old Testament. [1] This direct connection between wisdom thinking and creation justifies examining the possible role or influence of Genesis 1 through 3 on wisdom thinking.

Intertextuality [2] has been variously defined, but in this study we will use it to designate the interrelationship between several texts intentionally established by the author(s) of the most recent text, in order to communicate a message. [3] It assumes that the linguistics of the text are rooted in the literature and culture of the writer and that it contributes to the understanding of that body of literature. In order to set limits on the identification of intertextual references, it is necessary to find terminological and thematic connections between texts. [4] In this study, we will be examining the theme of creation and terminology that connects passages from the wisdom literature with creation terminology predominantly found in Genesis 1 and 2. These markers will help us identify possible quotes and allusions to the biblical creation narrative. We will begin our study with the book of Job and then move to Proverbs and Ecclesiastes.

CREATION MOTIFS IN THE BOOK OF JOB

It is generally recognized that the author of Job was acquainted with the creation account of Genesis and used it in the development of some of his arguments. [5] The book contains a significant number of creation motifs and discussions. We will only examine some of the evidence and its possible connections with Genesis.

CREATION OF HUMANS

Although we do not find an anthropogony in Job, the writer is acquainted with the creation of humans as recorded in Genesis. Elihu, when arguing that often humans do not ask for God’s help, states that “no one says, ‘Where is God my Maker’ [ʿōśāy]” (Job 35:10). [6] The participle ʿōśāy (“the One who created me”) is the qal participle of the verb ʿāśâ (“to make, do, create”), which is “the commonest verb for ‘create’” in the Old Testament. [7] This is the same verb used in Genesis 1:26 when God said, “Let Us make [ʿāśâ] man in Our image.” Elihu is assuming that God is the Creator of humankind. Job also uses the same participial form to refer to God as “He who made me” (Job. 31:15). He refers to himself as “the work” (maʿăśēh) of God’s hands (14:15), using a noun derived from the verb ʿāśâ. [8] The connection between the use of this verb in Job and in Genesis is strengthened by linking it to the “breath” of God and to “clay.”

Job sees God as a potter or artisan: “Your hands fashioned [ʿāṣab, ‘to shape, form’] and made [ʿāśâ] me altogether” (10:8). He proceeds to clarify that concept by saying, “You have made [ʿāśâ] me as clay [ḥōmer]” (v. 9). [9] The verbs ʿāṣab (“to fashion”) and ʿāśâ (“to make”) are used as synonyms to refer “to God’s act of creation.” [10] The term ʿāṣab stresses “the artistic skill of a craftsman in making an image” [11] or even an idol. Job conceives of God as an artisan who shaped and created humans from clay. Clay is the raw material used by the potter to produce what is intended. When used with reference to God, it points to God’s sovereignty and care for humans (e.g., Jer. 18:4–8; Isa. 64:8). In the context of creation, ḥōmer is the raw material God used to create humans. This term is not used in Genesis 1 and 2, but we find instead the phrase “of dust [ʿāpār] from the ground [ʾădāmâ]” (Gen. 2:7). In the book of Job, “clay” (ḥōmer) and “dust” (ʿāpār) are practically used as synonyms (Job 10:9). [12] Humans “dwell in houses of clay, whose foundation is in the dust” (4:19). When they die, they return to dust (34:15), an idea explicitly found in Genesis 3:19. The conceptual connection is quite clear.

In Genesis, the movement from clay to a living human being occurs when God breathes “into his nostrils [ʾap] the breath [nišmat] of life [ḥayyîm]” (Gen. 2:7). This is also the case in Job: “For as long as life is in me [literally, nišmatî bî, or ‘the breath is in me’], and the breath [rûaḥ] of God is in my nostrils [ʾap]” (27:3). The Hebrew term nĕšāmâ designates the divine gift of life bestowed to humans at creation, which constitutes the dynamic nature of human life that is sustained by the “spirit of God” (rûaḥ ʾĕlōah). [13] They are both given “to human beings as life-giving powers.” [14] When God withdraws both of them, the result is death (Job 34:14, 15). The book of Job presupposes that the writer knew about the anthropogony recorded in Genesis 2. [15]

There is some additional evidence that can be used to strengthen that conclusion. We will begin with Job 31:33. Job is speaking: “Have I covered my transgressions like Adam, by hiding my iniquity in my bosom?” The only linguistic connection with Genesis is the term ʾādām, which could be a proper name (Gen. 4:25) or a collective noun (i.e., “humankind”) (Gen. 1:27). This reference to ʾādām has been interpreted in different ways, [16] but the most obvious one is to take it as referring to Adam. [17] There is in the text a clear allusion to Adam’s attempt to conceal his sin before the Lord by blaming Eve (Gen. 3:12).

The second passage is found in one of the speeches of Eliphaz in which he asks Job, “Were you the first man to be born [yālad], or were you brought forth [ḥîl] before the hills?” (Job 15:7). Eliphaz is reacting to Job’s attack against the wisdom of his friends. [18] This passage deals with two different moments: existence and preexistence. The first is about the moment when the first man was born or came into existence—the image of birth is used to speak about creation—and the second takes us to the time before creation—before the hills were created. Was Job the first man created, or was he created before anything else? Here Psalm 90:2 could be useful: “Before the mountains [harîm] were born [yālad] or You gave birth [ḥîl] to the earth and the world, even from everlasting to everlasting, You are God.” This passage indicates that the verbs yālad and ḥîl can be used figuratively to refer to the divine work of creation. [19] In that case, the birth of the first man designates the creation of the first human being and would at least allude to Adam. One wonders whether Eliphaz is satirically asking Job whether he thinks he is wiser than the first man or even than God Himself. The possibility of the allusion to Adam is quite strong.

The last passage that we will briefly examine is Job 20:4–5, where Zophar asks Job: “Do you know this from of old, from the establishment [śîm, or ‘to place, to put’] of man [ʾādām] on earth?” The biblical background for this statement is Genesis 2:8: “The Lord God planted a garden toward the east, in Eden; and there He placed [śîm] the man [ʾādām] whom He had formed.” [20] The presence in Genesis 2:8 of the noun ʾādām and the verb śîm make the connection between the two passages practically unquestionable. What Zophar is bringing to the table “is traditional wisdom, which he pretends to be as old as Adam, and he marvels ironically that Job has not yet learned it.” [21]

ALLEGED PRESENCE OF OTHER ACCOUNTS

Some have found in Job 33:6 evidence of a non-biblical anthropogony of Mesopotamian origin. In the text, Elihu is addressing Job: “I belong to God like you; I too have been formed out [qāraṣ] of the clay.” It has been argued that in some myths dealing with the origin of humans the Akkadian cognate verb karaṣu, meaning “top inch off,” [22] takes as its object “clay” (Akkadian, ṭidda). In one of the myths, the goddess Mami (bēlet-kāl-ilī) “nipped off fourteen pieces of clay” [23] to create humans. In another one, two goddesses “nip off pieces of clay” [24] from the Abzu, give them human form, and place them in the womb of birth goddesses, where the clay figures develop and are later born as humans. Based on this mythology, it has been suggested that in Job we find at least traces of a myth that is significantly different from what is narrated in the Genesis account. [25]

One could perhaps give serious consideration to the previous interpretation if, first, it could be demonstrated that Elihu, coming from Uz and under the influence of Mesopotamian thinking, was not acquainted with the creation account found in Genesis. But this is not the case. In Job 33:3, as we already pointed out, he uses ideas now recorded in Genesis 2:7 to refer to the origin of his life: God gave him the breath of life. [26] Second, Elihu is attempting to answer some of the arguments used by Job to support his views. [27] In chapter 13, Job argued that it appears to be impossible to enter into a dialogue with God. Now, Elihu says to Job that, since they are both humans, they can enter into a dialogue with each other. They both were created from clay (Job 10:9; 33:6), and God gave them the breath of life (27:3; 33:4). In other words, “their common humanity is traced to creation.” [28] Elihu seems to be developing an argument based on the creation narrative recorded in Genesis 1. [29]

Concerning the meaning of the verb qāraṣ (puʿal formation or qal passive), the translation “to be nipped off” is only assigned to its usage in Job 33:6, and this is done under the influence of the Akkadian cognate. [30] There are four other usages in the qal formation in the Old Testament, in three of which its direct objects are the eyes. In such cases, the meaning seems to be “to blink or squint the eye” (e.g., Ps. 35:19; Prov. 6:13; 10:10). The phrase refers to a nonverbal communication consisting of a gesture that could express mockery, deception, or indifference. [31] In one case, the direct object is lips: “He who compresses his lips brings evil to pass” (16:30), probably referring to a gesture of disdain or deception. [32]

The Ugaritic cognate qrṣ could also be useful in attempting to establish the meaning of the Hebrew verb qāraṣ. Like the Hebrew verb, qrṣ has two slightly different meanings, namely “to nibble, to bite gently, or to gnaw and to mold or to form.” [33] The first usage is compatible with the passages in the Old Testament in which the verb qāraṣ, when used in conjunction with “eyes” or “lips,” means “to wink or squint” or “to compress.” The Ugaritic verb is also used with “clay” (Ug., ṯiṭ) to express the idea of shaping it into an effigy. This usage fits well into the meaning of the Hebrew verb in Job 33:6, thus, justifying the translation “formed out of the clay.” [34] Therefore, there is no need to postulate the presence of a Mesopotamian anthropogony or traces of it in Job.

CREATION AND DE-CREATION

Several scholars have noted the influence of the creation account in the prologue and the third chapter of Job. We will summarize the arguments and discuss them.

Prologue

It has been suggested that if we read Job 1 and 2 through the filter of Genesis 1 to 3, we will discover a correlation that is not accidental but that is the result of “a conscious adaptation of Genesis to the fabric of the new narrative.” [35] Only a few of the connections deserve consideration. [36] Although the case is not as strong as one would like it to be, it could be argued that there seems to be an intertextual connection with Genesis. As described, the family and possessions of Job appear to be a fulfillment of God’s command to Adam and Eve and to the animals to multiply and be fruitful (Job 1:2, 3; Gen. 1:22, 28). The blessing bestowed upon Adam and Eve has also been granted to Job (Job 1:10). The creation narrative seems to “create the atmosphere” [37] for the story of Job who is described as living in an idyllic state. This is reinforced by the reference to a seven-day cycle in Genesis, which is implied in Job (1:4, 5). [ [38]]

Job’s idyllic state of being changes in a radical way, and he experiences de-creation. Having lost everything, he is left with only his wife. It is probable that the tragedy begins during “the first day of the seven-day cycle, as his children celebrated ‘in the eldest brother’s house’ (Job 1:13). This is when creation should begin.” [39] Job’s first reaction to de-creation is summarized in the sentence: “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked I shall return there” (1:21). In Genesis 2, the human awareness of nakedness surfaces at the moment when, on account of sin, de-creation begins. Job is also realizing that he is heading toward death. The saying may be identifying the “womb” with the ground from which humans were taken and to which they will return (cf. Gen. 3:19). [40]

We should mention one more theological connection between the prologue of Job and Genesis 3. In both cases, we find an adversary— the serpent, the satan—in dialogue with another person—God in Job, and Eve in Genesis—but the fundamental attitude of the adversary is the same. The theological concept of a cosmic conflict is present in both, and the adversary’s primary object of attack is not Eve or Job; it is God Himself. In both cases he attacks God’s way of governing His creation. In the case of Eve and Adam, God is charged with restricting their self-expression and development by threatening them with death. In the case of Job, God is accused of having bought Job’s service by protecting Job and his family; the satan insinuates that if God would only withdraw that protection and stop being Job’s provider, Job would be able to express himself and would break his relationship with God, as Adam and Eve did. [41]

The creation account provides the background for the prologue of Job in order to emphasize the radical experience that Job went through. What he experienced was like the deconstruction of creation experienced by Adam and Eve but with one difference: he was innocent. This made his experience more intriguing.

Job’s First Speech

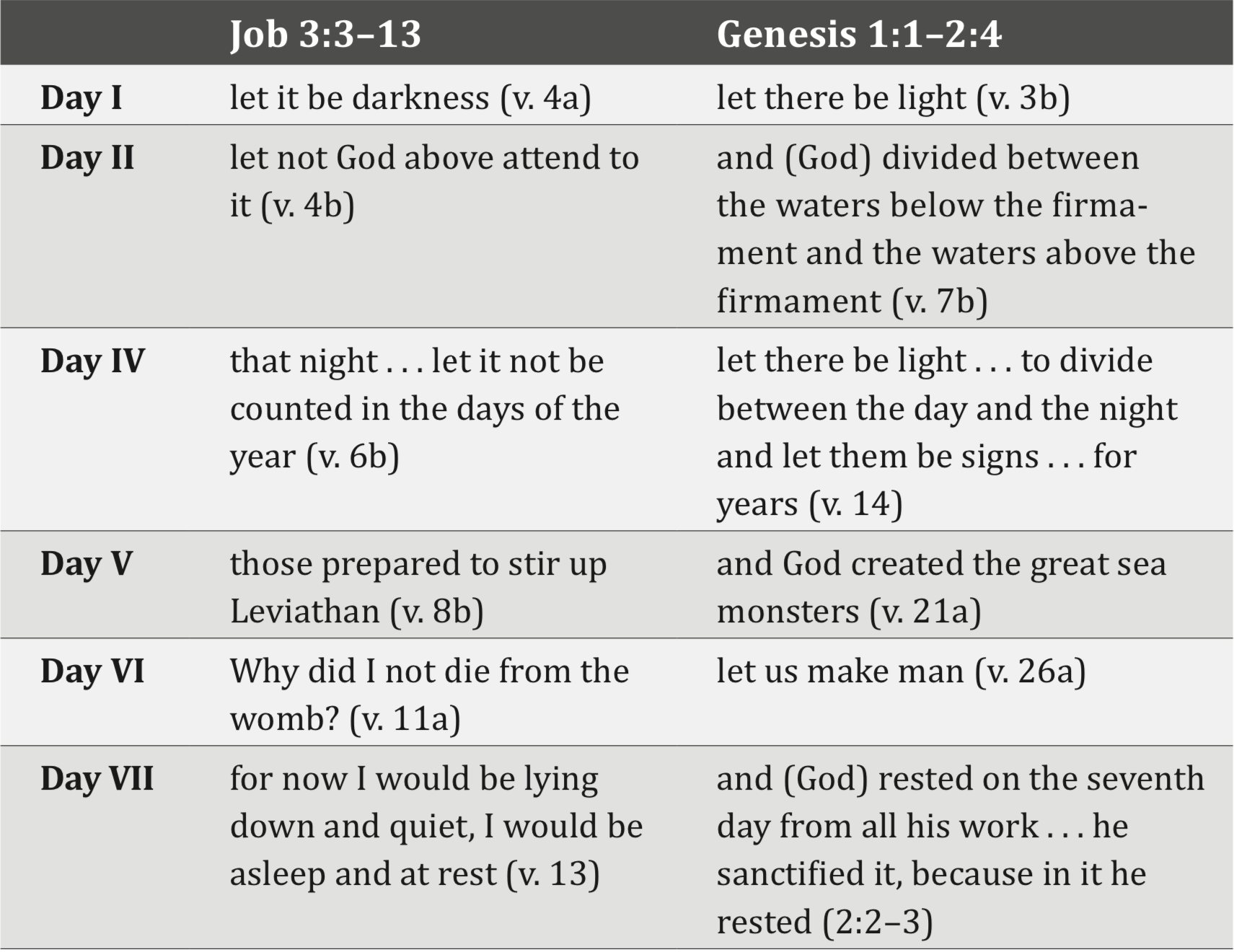

Some have found intertextual connections between Job 3 and the creation account in Genesis. [42] It is argued that what we find in Job’s first speech is “a counter-cosmic incantation designed to reverse the stages of the creation of the day of his birth, which were thought to be essentially the same as the stages of the seven-day creation of the world.” [43] What Job is doing is expressing a “death wish for himself and the entire creation.” [44] To support this connection, the following parallels have been identified: [45]

If the thematic connections are accepted, they would have to be interpreted in terms of reversal or de-creation. But not all the parallels are persuasive. There is no valid parallel for day two, and the third day is omitted. Overall, it could be argued that the creation account of Genesis 1:1–2:4 seems to provide the theological background for Job’s first discourse as he wishes for the impossible: the undoing of his creation. This is particularly the case with respect to the phrase “may that day be darkness [yĕhî ḥōšek]” (Job 3:4), which is basically the opposite of what we find in Genesis 1:3: “Let there be light” (yĕhî ʾôr). [46] But probably the most radical contrast is the one of rest. After creation, God “rested” (šābat) to celebrate the goodness of creation, but Job wants to “rest” (nūaḥ; cf. Exod. 20:11) in death, thus denying the value of his life (Job 3:13).

There are other linguistic parallels like, for instance, “days and years” (Gen. 1:14 [yôm, šānâ]; Job 3:6 [yôm, šānâ]) and light and night (Gen. 1:14 [laylâ, ʾôr]; Job 3:3 [laylâ], 9 [ʾôr]). It may also be important to notice a reference in Job 2:13 to a period of seven days and seven nights during which Job and his friends sat on the ground “with no one speaking a word.” This is a period of inactivity and deep silence in contrast to Genesis 1, where God is active every day and His voice is constantly heard. It may also be useful to observe that Job’s attempt to de-create his own existence takes place through the spoken word in the form of a curse, [47] whereas God’s creation takes place through the power of His spoken word that occasionally takes the form of a blessing (1:22, 28). [48] The idea that, in using Genesis as a background for the expression of his emotions and wishes, Job is aiming at the de-creation of the cosmos is foreign to the biblical text. [49]

Creation and God’s Speeches

The divine speeches in Job 38:1–40:5 are centered on the topic of creation as God takes Job in a cosmic tour. De-creation is not present in the text, but the Genesis creation account provides a background for the speeches. The first speech the Lord addresses to Job “consists of dozens of questions about the cosmos. They begin with creation and advance in a pattern that approximates the first chapter of Genesis” [50] (see Job 38:4–39:30). Of course, God is describing creation to Job as he experiences it, and consequently, we find comments on the presence of death on earth (38:17). This is possible because the speeches are not primarily about the creation of the earth and all that is in it. They are not even about creation as it came from the hands of the Creator. This is creation as Job encountered it and as we encounter it today. But the speeches presuppose that God is the Creator, and this idea goes back to Genesis.

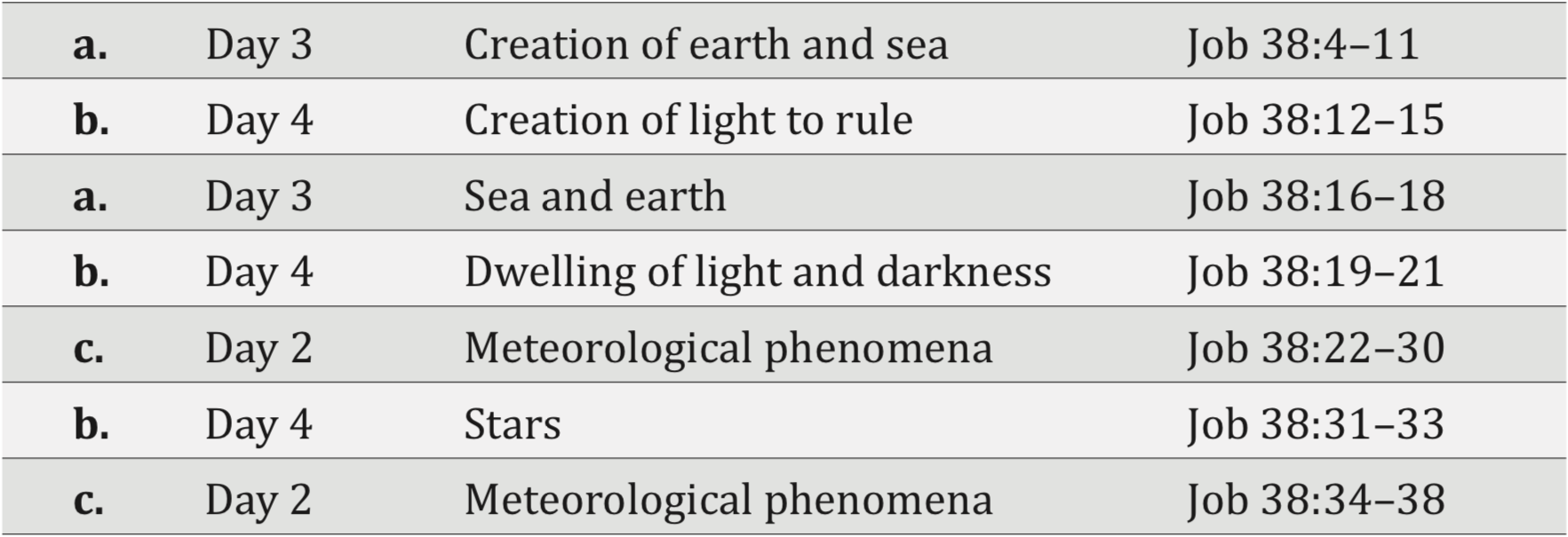

The first speech can be divided into two sections. [51] The first one is mainly about the earth, the sea, the stars, and meteorological phenomena (Job 38:8–38). The second part is about the fauna (38:39– 39:30). The speech begins with a reference to the moment when God is creating the earth (38:4–7). A building image is used for the divine act of creating the earth in which God is metaphorically described as “the architect (v. 5a), the surveyor (v. 5b), and the engineer (v. 6).” [52] This is not another creation narrative different from Genesis 1 but a metaphorical description of what we find in Genesis (Gen. 1:9, 10). It is the theological background of Genesis that allows for the use of the metaphor. [53] In the immediate context of the founding of the earth by the Lord, the separation of the waters or sea from the earth is mentioned. In Job 38:10, God separates the earth from the sea by setting limits to the sea in order for it not to encroach on earth. As in Genesis, this is creation by separation. Besides, in the rest of the speech, as we will see, Genesis 1 plays an important role. The use of the building metaphor “emphasizes the wisdom and discernment required in its grand design” [54]—something that only God possesses.

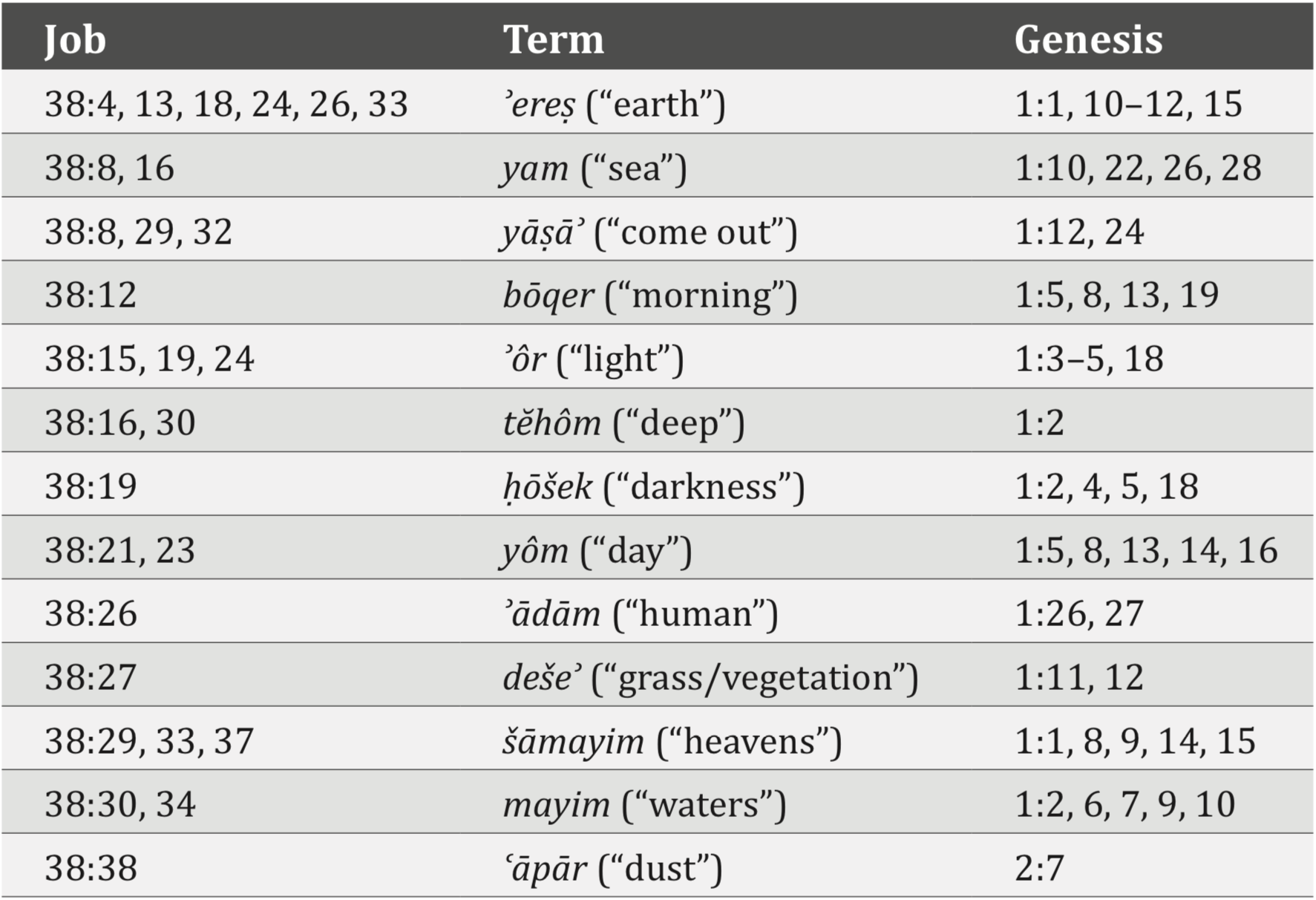

When we compare Job 38:4–38 with Genesis 1, we find a significant number of linguistic connections between the two passages. The following list summarizes the evidence:

These linguistic connections are, to some extent, to be expected in a speech about the natural world. But the fact that, within the speech itself, there is a clear reference to God’s creative activity (Job 38:4–7) indicates that the biblical writer was using the creation account of Genesis as a theological background for the speech. As we already indicated, God is depicted as the Architect and Builder who lays the foundation of the building, takes measures, and then finishes the project by placing the cornerstone (vv. 4–6). [55] From that moment on, the speech assumes that God is the Creator of everything in the cosmos. In this section, the speech is based on what God created during days two, three, and four of the creation week. [56]

The discussion is organized on the basis of the days of creation using a couple of panels (ABA’B’) and a chiasm (CBC’). The speech moves from the content of one day to the other in order to nurture curiosity and to introduce the unexpected. Therefore, Job could not anticipate what would come next in spite of his acquaintance with the creation narrative.

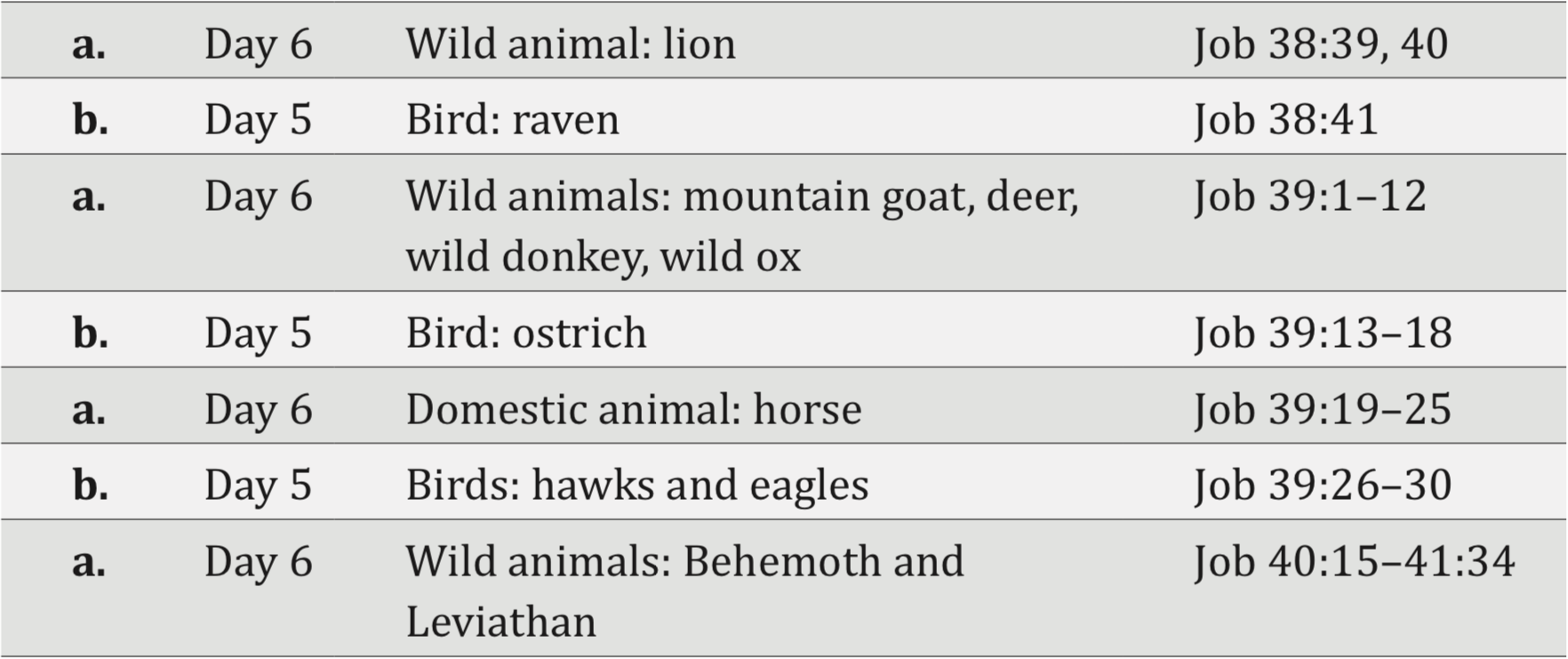

The rest of the first speech and most of the second speech (Job 40:6–41:34) are based on days five and six of the creation account and concentrate on the fauna or zoology. The material seems to be organized as follows:

The literary pattern found in this section is formed by three panels of the a plus b pattern and an incomplete one that creates a literary envelope for the content of the structure. The speeches presuppose the creation narrative of birds and animals, as recorded in Genesis 1, but it provides much more information concerning the habitat of the animals and their behavior. [57] The main purpose for using Genesis as a point of reference in the speeches is to provide for them an organizational pattern—a back-and-forth movement of the activities of days five and six. In other words, without Genesis 1 as a referent, the long list taken from the natural world does not reflect any particular order or pattern. [58]

SUMMARY

Our discussion has provided enough biblical evidence to suggest that what the book of Job says about creation is influenced by the creation account of Genesis. This is particularly the case with respect to the origin of humans. The author and the speakers were well acquainted with the creation narrative and used it whenever necessary to contribute to the development of the dialogue. In Job, the account of the creation of humans is used as a rhetorical tool to communicate several ideas. The first is the obvious one: it is employed to demonstrate the common origin of humankind (Job 33:6). Second, it highlights the fragility of human existence. Since life is fragile and brief—clay and breath—God should hasten to deliver Job from his pain or he will die (7:7, 21). Third, it is used to underline the value of human life. Since human existence was created by God and is, therefore, good, the Creator should not destroy it (10:8, 9; 27:3). Finally, Genesis’s anthropogony is used in Job to accentuate the superiority of God as Creator over humans as creatures (31:14, 15; 34:13–15).

In the prologue, the idea of the de-creation is influenced by the creation account and is used as a background for the reversal of Job’s fortunes. It is also employed to connect the adversary in Job with the serpent in Genesis 3. De-creation theology is particularly present in the first full speech of Job in chapter 3. In the divine speeches, Genesis 1 not only contributes to the development of their ideology, but in some instances, it also contributes to the organization of some of their content. This presupposes that the author of Job was exceptionally well acquainted with the creation narrative.

CREATION MOTIFS IN THE BOOK OF PROVERBS

In Proverbs, we find a significant number of texts addressing aspects of creation theology, clearly indicating that the writers knew about the creation account of Genesis 1 and 2. The new element, carefully developed in the book, is that God created through wisdom. This is stated very early in the book: “The Lord by wisdom founded the earth, by understanding He established the heavens” (Prov. 3:19; cf. Gen. 1:1).

HUMANITY AND MARRIAGE

God is the ʿōśēh (“the Maker or Creator”) of humans (Prov. 17:5), who, according to Proverbs 20:27, are also animated by the Godgiven “spirit,” literally “breath of life” (nĕšāmâ). In this passage, the term used for humans is ʾādām and together with nĕšāmâ provides a useful linguistic match to Genesis 2:7. Humans are male and female, united by God in a marriage relationship: “He who finds a wife finds a good thing [ṭôb] and obtains favor from the Lord” (Prov. 18:22). In this case, ṭôb is used in conjunction with the verb “to find,” and it probably means “to find (one’s)fortune,” [59] that is to say to find a person of great value. Its meaning is further clarified by the phrase “obtain favor [rāṣôn] from the Lord,” which means that the husband has been blesse d by the Lord. [60] The implication of the text is that “the husband has little to do acquiring such a prize. She is a gift from God.” [61] This idea goes back to Genesis 2:22–24 where God brings Eve to Adam and blesses both of them. The concept of marriage found in Proverbs is the one established in Genesis. A man and a woman are united in the presence of God; He blesses them, and a partnership is instituted among the three of them. At that moment, the couple makes a covenant with and before the Lord, [62] and the two of them establish a relationship of mutual, loving friendship (Prov. 2:17). [63]

WISDOM AND CREATION

The phrase ʿēṣ ḥayyîm, “tree of life,” is employed outside Genesis only in four passages in Proverbs. Even though it is used in three of these (Prov. 11:30; 13:12; 15:4) in a metaphorical sense, “the mere fact of the presence of this motif seems to provide a link to the important story of origins found in Genesis 1–3.” [64] Concerning the use of the same phrase in Proverbs 3:18, it has been argued that here we have a nonmetaphorical use of it, referring back to Genesis. [65] The passage reads: “She [Wisdom] is a tree of life [ʿēṣ ḥayyîm] to those who take hold of her, and happy are all who hold her fast.” The text gives the impression that, even here, the phrase is being used metaphorically to refer to the life-giving nature of wisdom. [66] The allusion to the Garden of Eden is argued by indicating that, in the context, we find terminology that is common to both. For instance, in Proverbs 3:13 the noun “man” (ʾādām) is used twice. This double use of the term is exceptional in the Hebrew Bible; in fact, it is unique. The argument is that “the verse obviously applies to any individual in general, but designating him by [ʾādām] rather than one of its alternatives is dictated by desire to emphasize and allusion to [hāʾādām] of the Garden of Eden story.” [67] It is also argued that Proverbs 3:19, 20 resembles 8:22–31, where the role of wisdom in creation is discussed and where we also find a connection with Genesis 4:4, 10. [68]

The most important argument, according to this interpretation, is based on the connection between Proverbs 3:17 and 18. In verse 17, we read about the “ways” (derek) and paths of wisdom that are pleasant and peaceful, and verse 18 begins with the tree of life. The suggestion is made that combining the words of the two verses yields the translation “her ways are the ways of/ toward the Tree of Life.” [69] It is then concluded that Proverbs 3:18 “signals us that the way (back) to the Tree of Life is through wisdom.” [70] In our opinion, this reading of verses 17 and 18 is hardly defensible. But the close connection between the “way” (derek) and the tree of life found in both Proverbs and Genesis is significant and supports the argument that we find here at least an allusion to Genesis 2 and 3. I will also suggest that, even if we conclude that the phrase “tree of life” is used metaphorically, the allusion to Genesis still stands. The text assumes that there was a tree of life and that literal access to it in the garden is no longer possible. The text, then, proceeds to teach that we can again have access to the tree of life through divine wisdom. [71]

WISDOM AND COSMOGONY

Proverbs in a unique way develops the role of wisdom in the creation of the world. While this emphasis on wisdom is not in Genesis, it is not presented here as an alternative to the Genesis account. On the contrary, we will argue that it enriches that account by taking us into the thoughts of the Creator. The key passage on the topic of creation is Proverbs 8:22–31, which is part of a wisdom poem [72] in the form of speech (Prov. 8:4–36), in which Wisdom is personified and invites humans to listen to her (vv. 4–11). The authority of her call to listen is based on her knowledge, her value for human existence (vv. 12–21), and her close relationship with the Creator (vv. 22–31). She can be a reliable guide for humans (vv. 32–36). We will concentrate our comments on verses 22 to 31 and examine some of their central ideas.

This passage is not properly speaking about creation but about Wisdom, but in the process, something very important is said about creation. With respect to creation itself, the passage could be divided in two sections. One of them is about the pre-creation condition and the other about creation itself. Although the main interest of the passage is not to describe creation along the lines of the Genesis creation account, a connection with Genesis is undeniable. [73] Proverbs is not a creation account but a highly poetic description of creation.

Pre-Creation State

The pre-creation state is depicted through negatives. This is done in Proverbs 8:24–26 using a particle of negation (ʾên) with the preposition bĕ (“when”) attached to it—“When there were no . . .” (bĕʾên, v. 24)—as well as an adverb of time (ṭerem) with the prefixed preposition bĕ—“Before . . .” (bĕṭerem, v. 25a; notice the preposition lipnê, or “before,” v. 25b)—and another preposition (ʿad) also accompanied by a negative—“While He had not yet made” (ʿad loʾ ʿāsâ, “until he had not made = before he had made,” v. 26). A partial description of the pre-creation condition of some elements of the earth is also found in Genesis 2:5, 6, where similar terminology is employed (“No shrub of the field was yet [ṭerem]; . . . no plant of the field had yet [ṭerem] . . . ; there was no [ʾên] man . . .”). In the case of Genesis 1, there is no description of the pre-creation state of the cosmos. Before cosmic creation, there was only God (Gen. 1:1), and this by itself indicates creatio ex nihilo.

According to Proverbs, before creation “there were no depths [tĕhōmôt],” [74] no “springs [maʿyān, ‘source of water’] abounding with water” (Prov. 8:24), and no “mountains” (hārîm) or “hills” (gĕbaʿôt, v. 25). God had not yet made the “earth” (ʾereṣ), the “fields” (ḥûṣôt), and “the first dust [ʿāprôt]of the world” (v. 26). [75] In other words, the earth as we know it—with water, mountains, hills, and dust—had not yet been created. According to Genesis, God created the “earth” (ʾereṣ; Gen. 1:2), the “dust” (ʿāpār; 2:7), and the “deep” (tĕhôm, 1:2), which is associated with “the springs” (maʿyānôt) of water (7:11; maʿyĕnôt tĕhôm, “the fountains of the deep”). [76] The mountains and the hills are not mentioned in Genesis 1, but since they are part of the earth as we know it, they are included in the list of what was not there before creation. [77]

Creation Itself

The wisdom poem moves from pre-creation to creation itself or to the moment when God was creating. We are given only a few examples of what He created, but they are framed by a reference to the “heavens” (šāmayim) at the beginning of the list (Prov. 8:27) and to the “earth” (ʾereṣ) at the end (v. 29). This takes us back to Genesis 1:1: “In the beginning God created the heavens [šāmayim] and the earth [ʾereṣ].” In between these two, Proverbs emphasizes the skies and water. God is described in the passage as the Architect who is building the cosmos and the earth: “He established [kûn] the heavens,” [78] “he inscribed [ḥāqaq, ‘to inscribe, decree’] a circle on the face of the deep [ʿal pĕnê tĕhôm]” (v. 27b), [79] “he made firm [ʾāmēṣ] the skies [šaḥaq] above” (v. 28a), [80] “fixed” (ʿāzaz, “to show oneself strong”)the springs of the deep (v. 28b), [81] set “boundaries” (ḥōq, “limit, regulation”) to the sea (v. 29a), and “He marked out [ḥāqaq, ‘to inscribe, decree’] the foundations [môsād] of the earth” (v. 29c). [82] The language describes the work of a Person who is constructing nothing less than the cosmos. [83]

Central Purpose of the Passage

The main interest of the passage is not on the creation of the cosmos but on the significance of wisdom. The brief discussion of the pre-creation period has the purpose of establishing that divine wisdom pre-existed, while the discussion about the divine act of creation reveals that during creation she was already with Him: “The Lord possessed me [qānānî] at the beginning [rēʾšît] of His way [darkô], before His works of old [mēʾāz, ‘from of old’]” (Prov. 8:22); “From everlasting I was established [nissaktî]” (v. 23); “When there were no depths I was brought forth [ḥîl, ‘to be in labor’]” (v. 24; also v. 25). The language used is highly figurative [84] and is basically taken from the experience of human reproduction.

Scholars are divided with respect to the meaning of the verb qānâ in Proverbs 8:22. It is generally recognized that its basic meaning is “to acquire,” from which other derived usages are possible (“to possess,” “to buy,” “to create,” and “to beget”). [85] What is strongly debated is whether the verb also means “to create.” It has been suggested that this usage may be implied in only two passages, namely Genesis 14:19 and 22. [86] In the context of Wisdom, the main possibilities are “to acquire,” “to possess,” and “to beget.” This means that the determining factor would have to be the immediate context. The context clearly supports the idea of begetting. Wisdom herself unambiguously states that she came into being through birth: “I was brought forth” indicates that at some point she was born. The Hebrew verb ḥîl used here is “a comprehensive term for everything from the initial contractions to the birth itself.” [87] It is, therefore, better to interpret the verb qānâ as referring to the moment of conception. [88] The moment when the action of the verb took place is identified as “at the beginning,” using the same Hebrew term employed in Genesis 1:1 (rēʾšît). “At the beginning of His way” [89] is clarified as “before His works of old.” When God began His work of creation, Wisdom was already with Him; He had already conceived her. In the next verse, the existence of Wisdom is apparently pushed back into eternity: “From everlasting [mēʿôlām] I was established [nissaktî]” (Prov. 8:23) [90].

The new verb nissaktî, “established me,” is also a difficult verb. The Masoretic Text vocalization indicates that it is the nipʿal form of the verb nāsak, “to pour out (a libation offering),” but this translation does not fit the context. [91] In what sense was Wisdom poured out?

Where was it poured if nothing else had been created? There are two other possible readings of the verb. The first is to consider the verb nāsak to be a by-form of the root n-s-k (nāsak II), meaning “to be woven, to be formed.” This by-form is used in Isaiah 25:7b: “The veil [noun massēkâ, designates a woven ‘covering,’ from the verb nāsak II] which is stretched [nāsak II, ‘to be woven, shaped’] over all nations.” The second possibility is that the verb nissaktî is from the root sākak II, meaning “to weave, shape,” and in the nipʿal formation (passive), “to be made into shape, manufactured.” [92] In this case, it would be necessary to repoint the Masoretic Text: nissaktî > nesakkōtî, a minor modification (the consonantal text would remain the same). The meaning of the two verbs would be basically the same.

What would then be the meaning of the phrase “from everlasting I was being woven”? The best parallel would probably be Psalm 139:13b, where the psalmist states: “You wove [sākak] me in my mother’s womb,” denoting the process of gestation inside the mother (cf. Job 10:11). Interestingly, the parallel verb in that verse is qānâ: “For you formed [qānâ] my inward parts.” The two verbs express different ideas—qānâ would designate the begetting, while sākak would refer to the development of the embryo. In the case of Wisdom in Proverbs 8, she is described as conceived or begotten by God (v. 22); in verse 23, her development is described as the process of weaving together the different parts of the embryo; and finally, in verses 24 and 25, the moment of her birth is described. [93]

Her birth seems to coincide with the act of creation in the sense that, at that moment, what was not yet was created: “When He established the heavens, I was there, when He inscribed a circle on the face of the deep, when He made firm the skies” (Prov. 8:27–29). Throughout the whole process of creation, Wisdom was with the Lord. She concludes saying, “Then I was beside Him, as a master workman [ʿāmôn]; [94] and I was daily His delight” (v. 30). As the Lord is creating, Wisdom is an object of His delight. It could very well be that the idea of delight is expressed in Genesis 1 through the use of the phrases “God saw that the light was good” (Gen. 1:4), “God saw that it was good” (Gen. 1:10, 12, 18, 21, 25), and “it was very good” (1:31). [95] God rejoices as He contemplates the works of His hands. The creation act is described in Proverbs 8:31, 32 as a cosmic playing activity (śāḥaq, “to laugh, play”), indicating not only how joyful it was but also how effortless the divine activity was. Both God and Wisdom rejoice as the cosmos is coming into existence in a context free from conflict and filled with joy. This theology is also at the foundation of the theology of creation in Genesis, where creation takes place free from conflict and as the result of the effortless power of God.

On the surface it could appear that the creation elements present in Proverbs 8:22–31 seem to be quite different from what we find in Genesis, but that is not the case. A few concluding remarks may be useful to establish their theological congruence. First, the image provided by these texts is that of a God Who effortlessly creates, assigns roles to the different elements, and establishes limits in order for everything to function in proper harmony.

Second, the language of birth is exclusively associated with Wisdom. Under the influence of ancient Near Eastern creation ideas, some have concluded that in our passage, Wisdom is a goddess. [96] But what the text seems to indicate is that Wisdom is a personification of a divine attribute.

Third, as compared to Genesis, Proverbs 8 allows us to look back before creation into the origin of Wisdom. Here “wisdom originates from God’s very self.” [97] In Genesis, we find a God who is fully active in creating, but here, He is portrayed as a God Who had been conceiving and weaving Wisdom—creating it—within Himself; this Wisdom later became the objective reality of the cosmos humans know and of which they are a part. [98] The brief mention of the beginning of creation in Proverbs 8 has been more fully developed in Genesis 1 and 2.

Fourth, the process of creation that we can detect in our passage is totally compatible with what we find in Genesis 1 and 2. In both cases, God is described as the Architect or Builder Who separated things and assigned specific roles to them. It is true that creation through the divine word is not fully visible in Proverbs, but it is not totally absent. In the poem, the order of creation was established through the divine command, suggesting the presence of the spoken word. This is particularly the case in Proverbs 8:29: “When He set for the sea its boundary [ḥoq] so that the water would not transgress [ʿābar] His command [peh].” The word translated “boundary” could also be translated “law, regulation,” [99] and here it would be designating the divine regulation governing the sea, which was not to be transgressed by it (notice the personification of the sea). The Hebrew word peh, translated “command,” means “mouth,” but by extension, it expresses the idea of the “spoken command” or what comes out of the mouth as a command (e.g., Gen. 41:40; Josh. 15:13). [100] The specific command given to the waters is explicitly mentioned in Job 38:11a: “Thus far you [the sea] shall come, but no farther.” [101] The phrase “would not transgress His command” means that the waters will not transgress what came out of the mouth of the Lord. We do have here a hint at creation through the spoken word.

SUMMARY

The creation theology found in Proverbs is related to the theology of creation recorded in Genesis 1 and 2. The creation of humans as male and female, united in marriage by the Lord, the references to the tree of life, and the overall theology of creation in Proverbs 8:22–31 unquestionably demonstrate that the author of the book was acquainted with the creation narrative in Genesis. The wisdom poem provides, through the use of highly figurative or metaphorical language, some insights not present in Genesis but compatible with it. It also expresses, in poetic form, ideas found in Genesis. The differences between the two enrich each other’s depiction of divine creation.

CREATION MOTIFS IN THE BOOK OF ECCLESIASTES

It is generally accepted that the book of Genesis has exerted some influence on Qohelet. [102] Our primary interest is on the topic of creation, and in this particular case, there are just a few passages where this influence is clearly present, indicating that the author was acquainted with Genesis 1 to 3. [103] One could begin with hebel, one of the most frequently used words throughout the book, commonly translated “vanity.” It seems to contain an echo of the name of the second son of Adam and Eve, Abel (hebel). [104] The noun designates that which is transitory and ephemeral, like Abel who appeared for a brief period of time and then, like a vapor, was gone. [105] Qohelet universalizes the experience of Abel and describes all, except God, as vain, ephemeral, or empty of ultimate meaning. [106]

There is only one reference to God as Creator, which may or may not be a reference to Genesis 1: “Remember also your Creator” (12:1). The term translated “Creator” is bôrēʾ, the participial form the verb bāraʾ (“to create,” a verb used several times in Genesis 1), which is occasionally used to designate the Creator (Isa. 40:28; 41:20; 42:5; 43:1, 15; 45:18; Amos 4:13). If we look at the context of the passage, it could be argued that Qohelet had in mind Genesis. [107] This is suggested by the allusion to the nature of humans in Ecclesiastes 12:7: “The dust [ʿāpār] will return to the earth [ʾereṣ] as it was, and the spirit [rûaḥ] will return to God who gave it.” We are here within the conceptual world of the creation of Adam in Genesis 2:7, according to which God created him from the “dust” (ʿāpār) of the ground and gave him the “breath of life” (nišmat ḥayyîm). [108] Qohelet is now using this ideology to describe what takes place when humans die—what belongs to God returns to Him and what was taken from the ground goes back to it (cf. Gen. 3:19).

The idea that “humans” (ʾādām) were created from the dust and that they will return to it is also mentioned in Ecclesiastes 3:19, 20. The context is a discussion of human mortality, and the conclusion is that from this perspective humans are like the animals (Eccles. 3:18). They were both created from the “dust” (ʿāpār), they both have the same “breath” (rûaḥ), and when they die, they return to the dust. Genesis establishes that animals and humans were created from the ground, albeit in significantly different ways (Gen. 1:24; 2:7), and they both are breathing creatures (1:30; 7:22). This is the biblical background for what Qohelet, in his own peculiar way, is arguing. [109]

Qohelet establishes another connection with Genesis when he states: “Behold, I have found only this, that God made [ʿāśâ] man [ʾādām] upright [yāšār], but they have sought out many devices” (Eccles. 7:29). In his search, this is what Qohelet has found to be true, and it constitutes an important statement in the sense that humans are responsible for their own actions. This verse “is an obvious reflection on the first few chapters of Genesis,” [110] though the vocabulary is in some cases different. The verb ʿāśâ and the noun ʾādām are both used in Genesis 1:26 for the creation of humans—the use of ʾādām in both passages is generic. In agreement with the theology of Genesis, Qohelet indicates that originally humans were created “upright” (yāšār, “morally straight”), [111] but that they lost this uprightness through their own machinations. [112] This theological reasoning is clearly based on Genesis 1 through 3.

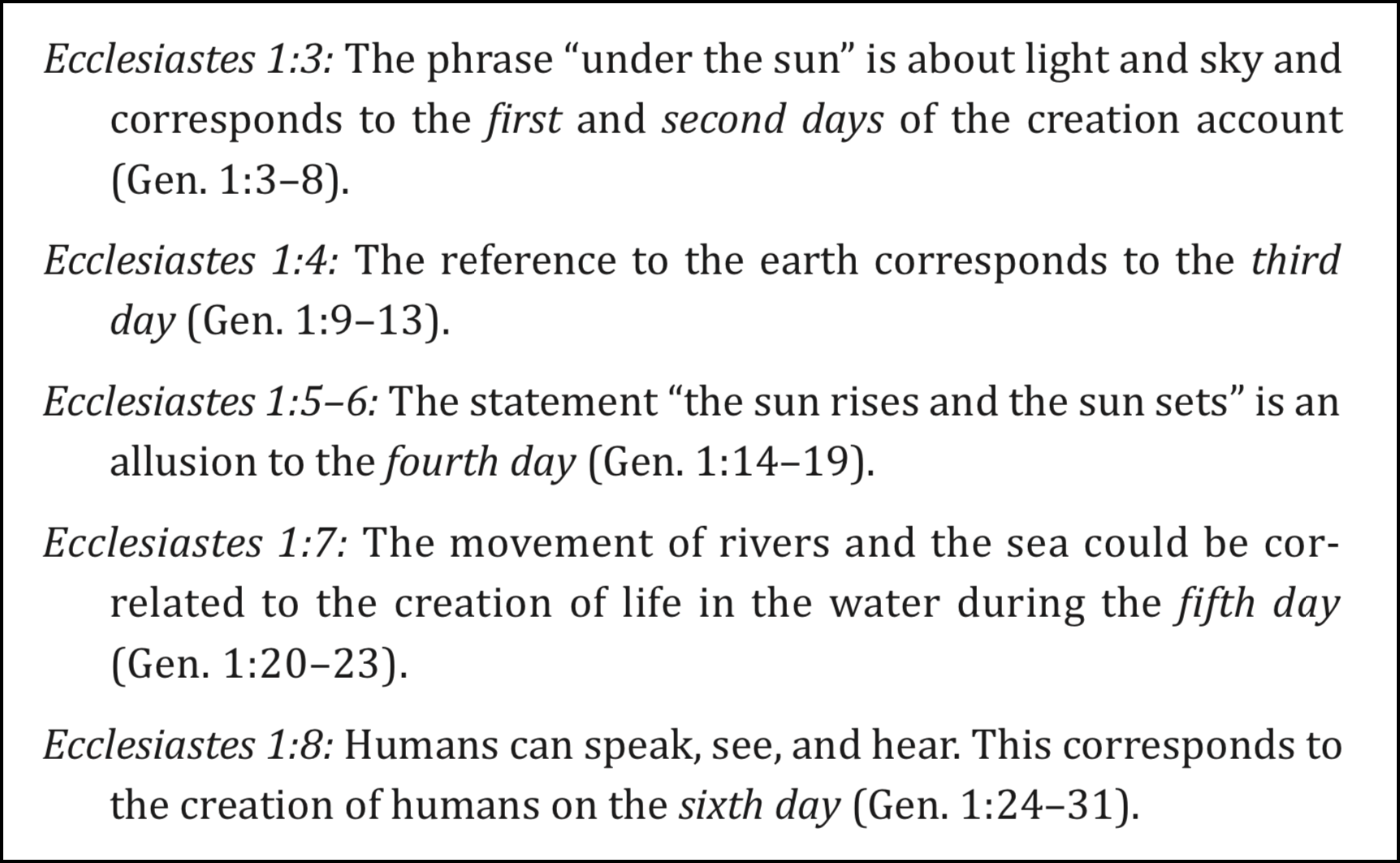

The creation of the world is alluded to at the beginning of the book in a poem that introduces the question of meaning. The poem is about “the back and forth movements of all the basic elements of Creation. . . . And yet nothing really new happens: no advantage is gained. It all seems purposeless.” [113] The elements of the cosmos mentioned in the passage seem to follow the order in which they are recorded in Genesis 1. [114]

The order of creation and its organized movement is read by Qohelet as indicating the absence of the new. “All,” the totality of creation, has become, in itself, vain and purposeless. The term “all” (kol) is also used in Genesis 1 to designate the totality of creation, but it refers to a creation that, after coming from the hands of the Lord, was “very good” (Gen. 1:31). [115] According to Qohelet, creation is no longer what it was.

SUMMARY

Qohelet is indeed aware of the creation account, but he uses elements of that narrative to argue that creation by itself is vain and does not provide for humans’ ultimate meaning. It is a dead end: “That which has been is that which will be . . . there is nothing new under the sun” (Eccles. 1:9). Human existence itself is ephemeral and, like that of the animals, will finally dissolve itself. But in accordance with the creation account, Qohelet recognizes that humans were originally created upright and that the condition in which they find themselves now is the result of their own choosing.

CONCLUSION

The three wisdom books that we have discussed contain a number of references to the creation account recorded in Genesis 1 and 2. Arguments assume the reliability of the creation account and its significance in the lives of the writers and their audience. The references to the creation of humans, animals, the natural phenomena, and the earth found in these books are, at times, brief summaries, allusions, or even passing comments, but they are all compatible with what we find in Genesis. The experience of pain and suffering and even death is contrasted with creation and understood as a decreation experience. The original goodness is acknowledged, and the present fallen condition of humans is credited to themselves.

The most penetrating contribution to the theology of creation is found in the personification of Wisdom and its connection to creation. God’s creation includes Wisdom, which was created in the mystery of the divine Being before it found expression in the objective phenomena of creation as we know it. Within that theology, creation through the word is assumed and even indicated in the text of Proverbs. This theology enriches the content of the creation narrative found in Genesis. The wise sages of the Old Testament were biblical creationists.

Ángel M. Rodríguez, ThD

Biblical Research Institute

Silver Spring, Maryland, USA

ENDNOTES

[1] On this topic, see the influential article by Walther Zimmerli, “The Place and Limit of the Wisdom in the Framework of the Old Testament Theology,” in Studies in Ancient Israelite Wisdom, ed. James L. Crenshaw (New York: KTAV, 1976), 314–26; and among many others, Roland E. Murphy and O. Carm, “Wisdom and Creation,” JBL 104, no. 1 (1985): 3–11; Leo G. Perdue, Wisdom & Creation: The Theology of Wisdom Literature (Nashville, Tenn.: Abingdon, 1994). The relation between wisdom and creation has been more recently reaffirmed: “An important interrelationship is established in the Wisdom literature between humanity and the natural world. God is the creator of the world, of humans, animals, plants, the elements, and of the order that holds the fabric of life together. The world to which the wisdom writers look is the natural one; proverbs often draw comparisons between unlike phenomena: one human, one nonhuman.” See Katharine J. Dell, “Wisdom in the OT,” NIDB, 5 (Cambridge, United Kingdom: University of Cambridge): 869–75. Obviously, there are other opinions, but the tendency is to recognize that creation plays an important role in the wisdom literature; see Katherine J. Dell, “Reviewing Recent Research on the Wisdom Literature,” ExpTim 119 (2008): 261–69.

[2] Intertextuality was first developed by Julia Kristeva, Semeiotiké: Recherches pour une sémanalyse, Collections Tel Quel (Paris: Le Seuil, 1969); and id., Revolution in Poetic Language, trans. Margaret Waller (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), probably under the influence of Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of dialogism. This literary approach has become popular in biblical studies, and scholars have produced a large body of research involving intertextuality. See among others, Danna Nolan Fewell, ed., Reading Between Texts: Intertextuality and the Hebrew Bible, LCBI (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 1992); George Aichele and Gary A. Phillips, eds., Intertextuality and the Bible, Semeia, 69/70 (Atlanta, Ga.: Society of Biblical Literature, 1995); Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (Oxford: Clarendon, 1985). For a brief introduction to intertextuality, see G. R. O’Day, “Intertextuality,” in Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation, ed. John H. Haynes, vol. 1 (Nashville, Tenn.: Abingdon, 1999), 546–48; and Ganoune Diop, “Innerbiblical Interpretation: Reading the Scriptures Intertextually,” in Understanding Scripture: An Adventist Approach, ed. George W. Reid (Silver Spring, Md.: Biblical Research Institute, 2005), 135–51.

[3] On the intentionality of the author in creating the interrelationship, see James D. Nogalski, “Intertextuality and the Twelve,” in Forming Prophetic Literature: Essays on Isaiah and the Twelve in Honor of John D.W. Watts, ed. James W. Watts and Paul R. House, JSOTSup, 235 (Sheffield, England: Sheffield, 1996), 102, 3.

[4] On the need for markers in identifying cases of intertextuality, see Cynthia Edenburg, “Intertextuality, Literary Competence and the Question of Readership: Some Preliminary Observations,” JSOT 35, no. 2 (2010): 138–47.

[5] See for instance, William P. Brown, The Seven Pillars of Creation: The Bible, Science, and the Ecology of Wonder (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 116; Samuel Balentine, Job, SHBC (Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 2006), 41–44; J. Clinton McCann, “Wisdom’s Dilemma: The Book of Job, the Final Form of the Book of Psalms, and the Entire Bible,” in Wisdom, You Are My Sister: Studies in Honor of Roland E. Murphy, O. Carm., on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, ed. Michael L. Barré, CBQMS, 29 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1997), 22; Tryggve N. D. Mettinger, “The God of Job: Avenger, Tyrant, or Victor?,” in The Voice from the Whirlwind: Interpreting the Book of Job, ed. Leo G. Perdue and W. Clark Gilpin (Nashville, Tenn.: Abingdon, 1992), 48, 49, 236n44. It has been suggested that “the Book of Job may be a midrash of Genesis 1–11.” See R. W. E. Forrest, “The Two Faces of Job: Image and Integrity in the Prologue,” in Ascribe to the Lord: Biblical & Other Essays in Memory of Peter C. Craigie, ed. Lyle Eslinger and Glen Taylor, JSOTSup, 67 (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1988), 391.

[6] Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations in this chapter are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. (www.Lockman.org)

[7] Helmer Ringgren, “עשׂה ʿāśâ,” in TDOT, vol. 11, 390.

[8] In Job 10:3, Job speaks of humans and particularly of himself as “the labor [yĕgîʿa] of Your hands.” In this case, he uses the verbal noun yĕgîʿa (“toil, labor”), from the verb yāgaʿ, or “to labor, to struggle,” in order to emphasize the special effort exerted by God in the creation of humans. See Gerhard F. Hasel, “יגע yāgaʿ,” in TDOT, vol. 5, 390.

[9] “As clay” is a literal translation of the Hebrew kaḥōmer and could be expressing the idea that God worked on the clay to fashion humans. Because of the parallelism of the two verbs, it could be that ʿāśâ is, in this particular case, expressing the idea of making or creating someone by molding clay (cf. 10:9; NIV).

[10] M. Graupner, “עצב ʿāṣab,” in TDOT, vol. 11, 281.

[11] John E. Hartley, The Book of Job, NICOT (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1988), 186, no. 6.

[12] See Helmer Ringgren, “חמר ḥmr,” in TDOT, vol. 5, 3.

[13] T. C. Mitchell, “The Old Testament Usage of Nešāmâ,” VT 11 (1961): 177–87, has strongly argued that the divine action of breathing into Adam the nĕšāmâ distinguishes humans from the animals. Since human life was a divine gift, and He is the One Who is constantly preserving it, it could be said that “breath as the characteristic of life shows that man is indissolubly connected with Yahweh.” See Hans Walter Wolff, Anthropology of the Old Testament, trans. M. Kohl (Philadelphia, Pa.: Fortress, 1974), 60.

[14] H. Lamberty-Zielinski, “נְ ָשׁ ָמה nešāmâ,” in TDOT, vol. 10, 67. David J. A. Clines writes, “Job is no doubt alluding to the creation narrative of God breathing into the nostrils (אפים, as here) of the first man the ‘breath of life’ (נשׁמת חיים; here רוח).” See Clines, Job 21–37, WBC, 18a (Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson, 2006), 646, 47.

[15] Lamberty-Zielinski, “נְ ָשׁ ָמה nešāmâ,” vol. 10, 66, has stated, “The point of departure for understanding nešāmâ in the OT is the oldest witness, Gen. 2:7.” Mitchell, “The Old Testament Usage,” 180–81, argues that nĕšāmâ in Job refers to the breath of God, “which he breathed into man at his creation.” He is specifically referring to Job 32:8; 33:4; 26:4; and 27:3.

[16] For a brief review of the different interpretation, see Clines, Job 21–37, 971, 72.

[17] This interpretation has been argued by, among others, Marvin H. Pope, Job: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, AB, 15 (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1965), 238; and Clines, Job 21–37, 1030.

[18] See David J. A. Clines, Job 1–20, WBC, 17 (Dallas, Tex.: Word, 1989), 349. The expression “first man” assumes that there was a first human being. Eliphaz sarcastically asks Job whether he is that man. A number of interpreters have found here a reference to the myth of the primeval man. This man was a mythical figure who was extremely wise. Supposedly traces of this myth are found in Ezekiel 28:11–19 and in Proverbs 8. The myth itself is not found in the Old Testament, and the figure mentioned in Ezekiel was not human but a cherub (Ezek. 28:16). The connection with Proverbs 8 is on a more solid ground, because there, the pre-existence of wisdom is affirmed using the language employed in Job 15:7: “Before the mountains were settled, before the hills I was brought forth” (yālad, “was born”; Prov. 8:25). But again, this is not about a primeval wise man but about divine wisdom. The presence of the myth of a primeval man in the Old Testament is a scholarly invention that still needs to be demonstrated (with Francis I. Andersen, Job: An Introduction and Commentary, TOTC, 14 [Downers Grove, Ill.: Inter-Varsity, 1976], 190).

[19] See J. Schreiner and G. J. Botterweck, “ילד yālad,” in TDOT, vol. 6, 80; and A. Baumann, “חיל ḥîl,” in TDOT, vol. 4, 345. Baumann suggests that this language serves to depict God as both father and mother (346, 47); see Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalms 2: A Commentary on Psalms 51–100, Hermeneia, trans. Linda M. Maloney (Minneapolis, Minn.: Fortress, 2005), 421.

[20] This is supported, among others, by Robert L. Alden, Job, NAC, 11 (Nashville, Tenn.: Broadman & Holman, 1993), 214; Edouard Dhorme, A Commentary on the Book of Job (Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson, 1967), 291; and Hartley, The Book of Job, 304.

[21] Clines, Job 1–20, 484.

[22] CAD K, 209; Jeremy Black, Andrew George, and Nicholas Postgate, A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian (Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz, 2000), 148. The verb is used to refer to the god “who dug out their clay” (ka-ri-iṣ ṭi-iṭ-ṭa-ši-na) from the Absu. See W. G. Lambert, Babylonian Wisdom Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960), 88–89 (line 277).

[23] W. G. Lambert and A. R. Millard, ATRA-ḪASĪS: The Babylonian Story of the Flood (Oxford: University Press, 1969), 61.

[24] “Enki and Ninmah,” trans. Jacob Klein, COS 1, no. 159 (1997): 517.

[25] The linguistic connection is argued by Dhorme, A Commentary, 488. See Carol A. Newsom, “The Book of Job: Introduction, Commentary, and Reflections,” in NIB, vol. 4, 568.

[26] The structure of Job 33:4–7 also indicates that verse 6 is to be read in the light of verse 4. It has been suggested that, in those verses, we find an ABAB literary pattern with “v. 4 corresponding to v. 6 and v. 5 to v. 7. In vv. 4 and 6, human nature is described in terms of the breath of God (v. 4) and clay (v. 6), as in Gen 2:7” (Newsom, “Book of Job,” vol. 4, 568).

[27] For a more detailed discussion, see Newsom, “Book of Job,” vol. 4, 568.

[28] Andersen, Job, 248.

[29] Additional evidence for Elihu’s acquaintance with the creation narrative is found in Job 36:27, where he comments, “For He [God] draws up the drops of water, they [the clouds] distill rain from the mist [ʾēd].” The Hebrew term ʾēd is only used here and in Genesis 2:6, where it stated: “But a mist [ʾēd] used to rise from the earth and water the whole surface of the ground.” The etymology and meaning of the Hebrew term ʾēd has been debated by scholars without reaching a final conclusion. The most recent study has concluded that “it appears from etymological, philological, linguistic, semantic, contextual, and conceptual arguments that Heb. ʾēd in Gen 2,6 is best rendered ‘mist/dew.’” See Gerhard F. Hasel and Michael G. Hasel, “The Hebrew Term ʾēd in Gen 2, 6 and Its Connection in Ancient Near Eastern Literature,” ZAW 112 (2000): 340. In the habitat of Adam and Eve, there was not rain, but the ground was watered by a mist rising from the earth (Gen. 2:5). The same term is used by Elihu to indicate that, even in the context of rain, the drops of water can be suspended in the air as vapor or mist that will also benefit the ground. Compare also Dhorme, A Commentary, 553; for a more detailed discussion of the complexity of the text, see Clines, Job 21–37, 825–27, 869–71.

[30] HALOT, vol. 3, 1148.

[31] The gesture may not consist in closing the eyes but in semi-closing them; see Michael V. Fox, Proverbs 1–9: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AB, 18a (New York: Doubleday, 2000), 220. F. J. Stendebach, “ַעיִן ʿayin,” in TDOT, vol. 11, 36, comments, “Scorn and derision are expressed by narrowing (qrṣ) the eyes.”

[32] “This proverb warns that evil comes not only in overt ways, such as violence (16:29), but also in underhanded and hidden plots, which can be indicated by subtle clues in people’s behavior such as body language.” See Andrew E. Steinmann, Proverbs, Concordia Commentary (Saint Louis, Miss.: Concordia, 2009), 370. In this particular instance, “the schemer compresses his lips and the wicked deed is as good as done.” See B. Kedar-Kopfstein, “ָפה שָׂ śāpâ,” in TDOT, vol. 14, 181.

[33] See G. del Olmo Lete and J. Sanmartín, Diccionario de la lengua ugarítica, Aula Orientalis Supplementa 7–8, vol. 2 (Barcelona: AUSA, 2000), 373.

[34] David J. A. Clines, ed., The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew, vol. 7 (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2010), 329, 30, provides two basic meanings for the verb, “pinch, compress” and “wink, blink,” and takes the puʿal to mean “be nipped” in the sense of “be formed.”

[35] Sam Meier, “Job I–II: A Reflection on Genesis I–III,” VT 39 (1989): 183.

[36] Meier, “Job I–II,” 184, 85, attempts to establish a connection between the phrase “there was a man in the land of Uz” (Job 1:1) and Genesis, but the connection is not found in Genesis 1 through 3. The idea that this land was to the east is related to the emphasis in Genesis 2, and the integrity of Job allegedly echoes the Genesis tradition and the original condition of Adam. These are possible connections, but they sound to me to be too strained.

[37] Ibid., 187.

[38] Meier comments, “His [Job’s] consequential reverence for the Sabbath may also be present, for, like God, he is not pictured as active on the seventh day. It is only after the seventh day had passed, ‘when the days of the feast had run their course’, that it is noted how ‘he would rise early in the morning and offer burnt sacrifices according to the number of them all’ (Job i 5).” See ibid., 187.

[39] Ibid., 188.

[40] Ibid., 189. Meier finds another connection between Job and Genesis in the phrase “touch his bone and his flesh” (Job 2:5). He recognizes that the literal meaning is that Job will experience bodily harm but argues here for a double entendre in the sense that the satan touches his wife who, based on Genesis 2:23, could also be described as his “bone and flesh.” The adversary touches her in the sense that she encourages Job to curse God and die (2:9). All of this may be possible, but it is far from clear that this is what the author of Job had in mind.

[41] For a more detailed discussion of the conflict described in the two narratives, see Angel M. Rodríguez, Spanning the Abyss: How the Atonement Brings God and Humanity Together (Hagerstown, Md.: Review & Herald, 2008), 30–32. Meier, “Job I–II,” 191–92, considers the connection between the adversary in heaven and the serpent in the garden to be a clarification. The heavenly scenes in Job are a midrash on Genesis 3 that answers two questions not addressed in Genesis: How does the serpent know so much about God’s command? Why does God not interrogate the serpent? The answer that, according to Meier, the prologue of Job provides is that God commissioned the serpent to test Adam and Eve. This way of reasoning reveals the creativity of Meier but not the clear intention of the biblical writer.

[42] For example, Michael Fishbane, “Jeremiah IV 23–26 and Job III 3–13: A Recovered Use of the Creation Pattern,” VT 21 (1971): 151–67; Hartley, The Book of Job, 101–2; Perdue, Wisdom & Creation, 133, 34; William P. Brown, The Ethos of the Cosmos: The Genesis of Moral Obligation in Genesis (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1999), 322–25; McCann, “Wisdom’s Dilemma,” 22.

[43] Hartley, The Book of Job, 101–2. He is relying on the work and conclusions of Fishbane, “Jeremiah IV 23–26.”

[44] Ibid., 153. See also Brown, Cosmos, 322.

[45] As displayed by Hartley, The Book of Job, 102; see also Fishbane, “Jeremiah IV 23–26,” 154.

[46] See Leo G. Perdue, “Job’s Assault on Creation,” HAR 10 (1986): 308; Clines, Job 1–20, 84; and Newsom, “Book of Job,” vol. 4, 367.

[47] See Perdue, Wisdom & Creation, 133.

[48] In Job 31:38–40, there is a statement, which is part of his declaration of innocence, clearly suggesting a connection with Genesis. Job states: “If my land cries out against me, and its furrows weep together; if I have eaten its fruit without money, or have caused its owners to lose their lives, let briars grow instead of wheat, and stinkweed instead of barley.” It has been correctly argued that “the punishment of this crime echoes Genesis 3:17–18 and 4:12, the curse God placed on the soil because of human disobedience in the first instance and fratricide in the second. Thorns and stink weed will grow instead of wheat and barley. Sterility will replace productivity of the soil.” See Perdue, Wisdom & Creation, 167.

[49] See Clines, Job 1–20, 87. Clines approvingly quotes J. Léveêque, Job et son Dieu;essai d’exégèse et de théologie biblique, vol. 1 (Paris: Gabalda, 1970), 336: “At no time does Job claim to deregulate the creation or reduce the cosmos to the same state of night as his soul experiences at this moment; it should be stressed that his malediction relates only to one particular day and one particular night.”

[50] Alden, Job, 369.

[51] For a discussion of the literary structure of the speeches, see David J. A. Clines, Job 38– 42, WBC, 18b (Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson, 2011), 1085–88, 1092–94, and 1176–78.

[52] Norman C. Habel, The Book of Job: A Commentary (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1985), 537.

[53] The first speech uses a number of other metaphors. For instance, it uses the metaphor of birth to refer to the origin of the sea (Job 38:8) and of the frost and the ice (v. 29). The rain is described as the result of tipping over “the water jars of the heavens” (v. 37). The words of Andersen, Job, 274–75, are apropos here: “The origin of the sea is described by vivid use of the metaphor of childbirth. It is idle to make this yield a scientific cosmology, since any Israelite knew as well as we do that poets go in for such fancies and do not expect us to believe that God makes rain by pouring water from tilted waterskins (38:37).”

[54] Habel, Job, 537.

[55] The phrase ʾeben pinnātāh, “cornerstone,” could refer to a foundation stone or to the capstone placed at the top of the structure to hold it together (see E. Mack, “Cornerstone,” in ISBE vol. 1, 784; Pope, Job, 292). I understand it here as the capstone, because it is immediately stated that “the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy” (Job 38:7), indicating that they were celebrating the conclusion of the work of creation (see Clines, Job 38–42, 1100). Some scholars tend to take it as designating the cornerstone of a foundation; for example, Andersen, Job, 274, and Hartley, The Book of Job, 495. Others understand it to mean “the ‘corner-stone’ which crowns the edifice” (Dhorme, A Commentary, 577). The truth is that the usage of the Hebrew phrase is still being debated, but the meaning “capstone” is well attested in the Old Testament (e.g., Prov. 25:24; Zeph. 1:16). See Manfred Oeming, “ִפּנָּה pinnâ,” in TDOT, vol. 11, 587. Jeremiah 51:26 seems to establish a distinction between foundation stone and capstone. Hartley, The Book of Job, 495n20, suggested that the singing of the sons of God corresponds to the joy of the Jews when the foundation of the temple was being laid (Ezra 3:10, 11). But the Hebrew phrase we are discussing is not used in that text.

[56] Since it would not be difficult to assign the material found in Job to other days of the creation narrative, I want to provide some of my reasons for dividing the verses the way I have grouped them. Job 38:4–11 seems to describe, in highly poetic language, the moment when the earth is separated from the sea, as recorded in Genesis 1:9, 10. According to Job, this was the moment when God firmly established the earth and set geographical limits to the sea. This was also the time when the sons of God rejoiced (Job 38:7). The passage fits better with the divine activity on the third day of creation. One could also assign Job 38:12–15 to the first day of creation, when God separated light from darkness. But the emphasis in Job is on the continuous work of the light or dawn in ruling over the earth (see Habel, Job, 539, who refers to morning and dawn here as “Yahweh’s agents for regulating daily life on earth”). This fits better in Genesis 1:14–18 (the fourth day). Job 38:16–18 raises the question of the mystery of the depth of the sea and the expansion of the earth. This assumes that they have been separated from each other as described in Genesis 1:9, 10 (the third day). In the case of Job 38:19–21, light and darkness are not only separated from each other (first day in Gen. 1:3–5), but the question of their abode is also raised. This last element seems to be related to the fourth day when the connection of light and the two great lights were established. The two lights were permanently to separate light from darkness (Gen. 1:16–18). What is described in Job 38:22–30 is not mentioned in Genesis. This is a description of meteorological phenomena as was known in the time of Job (snow, hail, lightning, torrential rains, etc.). But it is because God, during the second day of creation, separated the waters below from those above that these natural phenomena are possible (Gen. 1:6–8). The reference to astronomical phenomena in Job 38:31, 32 can be easily connected to the mention of the stars during the fourth day of creation (Gen. 1:16). In Job 38:34–38, we are taken back to meteorological phenomena (clouds, rain, and lightning). As indicated above, this could be connected to the second day.

[57] The interpretation of Behemoth and Leviathan is a matter of debate among scholars. It is generally believed that Behemoth stands for the hippopotamus and Leviathan for the crocodile and that their descriptions are exaggerated in order to point to their specific function in the divine speech. There are four main interpretations, three of which argue that the two animals are used as symbols of something beyond themselves: (1) the two animals are used as symbols of the wicked; (2) they represent the enemies of the people of Israel; (3) they are mythical figures symbolizing chaos; (4) they are, like Job, creatures of God. See the discussion in Habel, Job, 557, 58. The last view has been defended by Clines, Job 38–42, 1183–86, 1190–92. It is not necessary for our purpose to get into this debate. Since it is generally accepted that the terms designate real animals, we can include them in the list of animals created by God, even if they are being employed as symbols of evil. In fact, it could be argued that all the other birds and animals included in the list seem to be used as symbols or at least they are included for some specific reason.

[58] Andersen, Job, 272, writes: “The list is assorted, with no strict order. It begins with some cosmic elements, moves to meteorological phenomena and ends with animals and birds. The horse seems to be the only domesticated animal mentioned.”

[59] HALOT, vol. 2, 371.

[60] The semantic field of the noun rāṣôn includes the idea of bĕrākâ, “blessing.” See H. M. Barstad, “ָר ָצה rāṣâ,” in TDOT, vol. 13, 625.

[61] Roland E. Murphy, Proverbs, WBC, 22 (Dallas, Tex.: Word, 2002), 138; see also Richard J. Clifford, Proverbs, OTL (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 1999), 174.

[62] The understanding of marriage as a covenant in which God is involved as a witness is implicitly found in Genesis 2:21–24, but it is also present in other places in the Old Testament (e.g., Mal. 2:14). See Fox, Proverbs 1–9, 120, 21.

[63] “The companion of her youth” in Proverbs 2:17 is obviously the husband. The Hebrew word ʾallûp means “companion or friend,” and it includes the ideas of intimacy and affection (Fox, Proverbs 1–9, 120). In this passage, “ʾallûp describes the most intimate and tender of friends, one’s own spouse.” See Eugene H. Merrill, “אלף ʾlp I learn, teach; ַאלּוּף ʾallûp familiar, friend,” in NIDOTTE, vol. 1, 416. There has been some discussion concerning the identity of this woman, whether she is an Israelite or not. The phrase “the covenant of our God” clearly refers “to the marriage bond as a sacred covenant,” and this suggests that the woman “would refer to an adulterous Israelite.” See on this Murphy, Proverbs, 16.

[64] Gerald A. Klingbeil, “Wisdom and History,” in DOTWPW, 872.

[65] Victor Avigdor Hurowitz, “Paradise Regained: Proverbs 3:13–20 Reconsidered,” in Sefer Moshe: The Moshe Weinfeld Jubilee Volume: Studies in the Bible and the Ancient Near East, Qumran, and Post-Biblical Judaism, ed. Chaim Cohen, Avi Hurvitz, and Shalom M. Paul (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2004), 49–62.

[66] So, for instance, Howard N. Wallace, “Tree of Knowledge and Tree of Life,” in ABD, vol. 6, 658; Heinz-Josef Fabry, “ֵעץ ʿēṣ,” in TDOT, vol. 11, 274.

[67] Hurowitz, “Paradise Regained,” 57.

[68] Ibid., 59.

[69] Ibid., 60.

[70] Ibid.

[71] See Clifford, Proverbs, 55; L. Alonso Schökel and J. Vilchez, Sapienciales I: Proverbs (Madrid: Ediciones Cristiandad, 1984), 185.

[72] On the topic of wisdom poems in the Old Testament, see J. A. Grant, “Wisdom Poem,” in DOTWPW, 891–94. There is a significant amount of literature on Proverbs 8. See, among others, G. Landes, “Creation Tradition in Proverbs 8:22–31 and Genesis 1,” in A Light unto My Path: Old Testament Studies in Honor of Jacob M. Myers, ed. H. N. Bream et al. (Philadelphia, Pa.: Temple University, 1974), 279–93; M. Gilbert, “Le discours de la Sagesse en Proverbes 8,” in La Sagesse de l’Ancien Testament, ed. M. Gilbert (Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press, 1979), 202–18; G. Yee, “An Analysis of Prov 8 22–31 According to Style and Structure,” ZAW 94 (1982): 58–66; Perdue, Wisdom & Creation, 84–94. Among the commentaries, see Fox, Proverbs 1–9, 263–95.

[73] The question of creation in Proverbs 8 and Genesis 1 was explored by Landes, “Proverbs 8:22–31,” 279–93. He points to similarities as well as differences. He correctly concludes that Proverbs 8:22–31 “does not seek to be a creation story in poetic form; nor does it necessarily reflect a full account of Yahweh’s creation activity. Thus, it should not be judged by what it omits in relation to Gen 1” (282).

[74] The clear implication in the inclusion of tĕhōmôt in this list is that it was also created by God. This is important, because in Genesis 1:2, although the creation of tĕhōm is not explicitly addressed, it could be argued that its creation is implicit in 1:1.

[75] Concerning the phrase “the first dust of the earth,” it has been suggested that “although this could be taken simply at face value, allusions to the creation story in context imply that this is a veiled reference to the formation of Adam from the dust (Gen 2:7). The Hebrew of v. 26 literally reads, ‘Before he made . . . the head of the dusts of the world.’ In Gen 1–2 ‘dust’ is associated only with the creation of humanity; there is no account of the creation of dust itself. The ‘dusts of the world’ is humanity, formed of the dust; and its head is Adam.” See Duane A. Garrett, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, NAC, 14 (Nashville, Tenn: Broadman, 1993), 109; Garrett points to the phrase “son of man or Adam” in Proverbs 8:31.

[76] See Landes, “Creation Traditions in Proverbs 22–31,” 283–84, 286–87.

[77] It may be correct to argue that the text is affirming that mountains and hills were part of the geography of the earth as it came from the hands of the Creator.

[78] The verb kûn and its derivatives denote “energetic, purposeful action, aimed at forming useful enduring places and institutions, with a secondary element asserting the reliability of statements.” See Klaus Koch, “כון kûn,” in TDOT, vol. 7, 93. The idea is that when God created the heavens He assigned to them usefulness and permanency.

[79] This same phrase is used in Genesis 1:2. Some have found in the phrase God “inscribed a circle on the face of the deep,” a reference to ancient Near Eastern cosmology: “The passage reflects the notion, influenced by Babylonian cosmogony, that the earth is a disk surrounded and bounded by the primeval ocean, with the dome of the heavens fixed above.”SeeErnst-JoachimWaschke,“ְתּהוֹם tehôm,”inTDOT,vol.15,579;similaralso,Clifford, Proverbs, 96. The phrase is describing something that is also found in Genesis 1, namely, creation through separation or by establishing proper boundaries, which in this case, consisted of separating “the sea from the dry ground.” See G. Liedke, “חקק ḥqq to inscribe, prescribe,” in TLOT, vol. 2, 470. The reference could be to the horizon, but what the text is affirming is that God fixed the limits or boundaries of the sea in order to establish the order of creation. Compare Garrett, Proverbs, 109; Steinmann, Proverbs, 211; William D. Reyburn and Euan McG. Fry, A Handbook on Proverbs, UBS Handbook Series (New York: United Bible Societies, 2000), 192–93. The phrase “inscribe a circle” could be a Hebrew idiom, similar to the English idiom “to draw a line,” meaning to circumscribe or set limits to something without any reference to a literal circular shape. The idea of setting specific boundaries to the waters is further developed in verses 28 and 29. I would suggest that the phrase “inscribed a circle on the face of the deep” is clarified in verses 28 and 29: “When the springs of the deep became fixed, when He set for the sea its boundary so that the water will not transgress His command” (on this last phrase, see the discussion to follow). This is about constructing the cosmos and assigning functions and boundaries to its different components.

[80] The verb ʾāmēṣ means “to strengthen, to make strong” and the noun šaḥaq means “fine dust or cloud.” Perhaps the idea is that God made the clouds powerful enough to be suspended in the air by themselves; see Bruce K. Waltke, The Book of Proverbs Chapters 1–15, NICOT (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2004), 415.

[81] The meaning of the verb ʿāzaz is not exactly “to fix” but “to strengthen” or “to make strong.” In context, the verb is probably indicating that God created the strong springs or sources of water that feed the deep.

[82] The “foundations [môsdê] of the earth” is an image taken from the field of architecture and depicts the earth as a building resting on foundations (cf. Jer. 51:26). “Marked out” seems to be a good translation of the verb ḥāqaq, but the question is what it is referring to. If we take into consideration that the verb also means “to decree,” then it would probably refer to the work of the architect in defining the parameters within which the foundations would function. But the fundamental idea seems to be that, at the moment of its creation, God provided stability to the earth. The language is highly metaphorical; cf. 2 Sam. 22:8, where we read about the foundations of the heavens—before the presence of God the whole creation becomes unstable and shakes.

[83] See Gale A. Yee, “The Theology of Creation in Proverbs 8:22–31,” in Creation in the Biblical Traditions, ed. Richard J. Clifford and John J. Collins, CBQMS 24 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1992), 91–93.

[84] The highly metaphorical language used in the poem has been discussed by Gale A. Yee in ibid., 85–95.

[85] HALOT, vol. 3, 1111–13.

[86]SeeEdwardLipiński,“ָקנָה qānâ,”inTDOT,vol.13,59;seealsoWernerH.Schmidt, .1152 ,3 .qnh to acquire,” in TLOT, vol קנה“

[87] A. Baumann, “חיל ḥyl,” in TDOT, vol. 4, 345.

[88] See, among others, Lipiński, in TDOT, vol. 13, 61.

[89] The divine derek (“way”) is His work, which in our text primarily refers to His creative work or the time when He began His work of creation. See Fox, Proverbs 1–9, 280–81.

[90] “When עו̇ ָלם [‘remote time,’ ‘eternity’] refers to the era before the creation of the world, as it does here, or when it refers to God’s continuing existence into the eternal future, its meaning is ‘eternity.’ Sometimes it is best rendered with an adjective, ‘everlasting, eternal.’” See Steinmann, Proverbs, 210. When it is accompanied by the preposition min, as is the case here, it could be translated “since eternity.” See Ernst Jenni, “ע ֹו ָלם ʿôlām eternity,” in TLOT, vol. 2, 854.