©Copyright 2018 GEOSCIENCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE

11060 Campus Street • Loma Linda, California 92350 • 909-558-4548

“WHEN DEATH WAS NOT YET”: THE TESTIMONY OF BIBLICAL CREATION

by

Jacques B. Doukhan,

DHebLett., ThD

Andrews University

Berrien Springs, Michigan, USA

This article was originally published as a chapter in the book “The Genesis Creation Account and Its Reverberations in the Old Testament."

INTRODUCTION

The question of the origin of death is interpreted differently, depending on whether one holds to the theory of evolution or to the biblical story of creation. While evolution teaches on the basis of observation that death is a natural and necessary process in the hard struggle for life—death is a part of life—the Bible tells us, on the contrary, that death was not a part of the original plan. From the testimony of biblical creation, four arguments can be used to support this assertion: (1) the world was originally created good, (2) the created world was therefore not yet affected by death, (3) death was not planned, and (4) death will no longer be in the new re-created world of the eschatological hope.

METHODOLOGICAL NOTE

Although my question is theological and philosophical (Was death a part of God’s original creation?), my approach to finding the answer will be essentially exegetical. This means that I will seek within the biblical text literary clues suggesting that not only was death not a part of God’s creation but also that the biblical text attests to a specific intentionality about this assumption.

THE GOOD OF CREATION

The use of the verb bārāʾ, “to create,” to describe God’s operation of creation and the regular refrain “it was good” (e.g., Gen. 1:4) to qualify His work testify to the goodness of creation.

THE VERB BĀRĀʾ

The divine work of creation is rendered through the use of the verb bārāʾ, which is often used in parallelism with ʿāśâ, “to do, to make” (Isa. 41:20; 43:1, 7; 45:7, 12, 18; Amos 4:13), implying a positive connotation that is on the opposite range of meanings to the negative ideas of destruction and death. In addition, the root bārāʾ denotes the concept of producing something new, which has nothing to do with the former condition (Isa. 41:20; 48:6, 7; 65:17), and marvels, which have never been seen before (Exod. 34:10). This usage of the verb bārāʾ does not therefore allow the sense of separating, which has sometimes been advocated,[1] for the simple reason that this interpretation does not take the following arguments into consideration:

(1) Semantic argument. Although the Genesis creation story contains a series of separations, this does not mean that the Hebrew verb bārāʾ means “separate.” If it were the case, why did the biblical author choose to use the verb bārāʾ (seven times in the creation narrative: Gen. 1:1, 21, 27 [three times]; 2:3; 2:4a), instead of the specific verb hibdîl, “to separate,” which is used in the same context when the idea of separation is really intended (1:4, 6, 7, 14, 18)?

(2) Logical argument. The other biblical occurrences of the verb bārāʾ would not make sense if the verb was translated “separate” instead of “create” (see especially Gen. 1:21; Exod. 30:10; Deut. 4:32; Isa. 45:12). Also, the fact that the verb bārāʾ has only God as a subject, whereas the verb hibdîl, “to separate,” generally has humans as subjects, testifies to the fundamental difference of meaning between the two verbs.

(3) Syntactical argument. The use of the same emphatic particle of the accusative et, after the verb bārāʾ, introducing one or several objects (Gen. 1:1, 21, 27), implies the same syntactical relation between them and, thus, supports the interpretation of “create” rather than “separate,” which implies different syntactical relations, with the use of a different set of prepositions: bên . . . ûbên (“between . . . [and] between”) or min . . . lĕ (“from . . . to”).

(4) Linguistic argument. The argument that the verb bārāʾ is related to the rare piel form of a root brʾ, which has the meaning of “separate” or “divide,” to support the interpretation of “separate,” is hardly defensible, since this verb is derived from a different root brʾ iii.[2]

(5) Ancient Near Eastern argument. In ancient Egypt, as well as in Mesopotamia, the divine operation of creation is similarly rendered by the verbs “create,” “make,” “build,” and “form,”[3] but never by the verb “separate” or “divide.”

(6) Translation argument. The Septuagint translates the verb bārāʾ generally by ktizō, “create” (seventeen times), and poieō, or “make” (fifteen times),[4] but never by “separate” or “divide.”

THE REFRAIN “IT WAS GOOD”

The divine work of creation is at each stage of its progress unambiguously characterized as ṭôb, “good” (Gen. 1:4, 10, 18, 21, 25) and at the end of the last step as ṭôb mĕʾōd, “very good” (Gen. 1:31). The meaning of the Hebrew word ṭôb needs to be clarified here. Indeed, the Hebrew idea of good is more total and comprehensive[5] than what is implied in the English translation. It should not be limited to the idea of function, meaning that only the efficiency of the operation is intended here.[6] Rather, the word ṭôb may also refer to aesthetic beauty (Gen. 24:16; Dan. 1:4; 1 Kings 1:6; 1 Sam. 16:36), especially when it is associated with the word rāʾâ, “see,” as is the case in the creation story (Gen. 1:1, 4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31).

The word ṭôb may also have an ethical connotation (1 Sam. 18:5; 29:6, 9; 2 Sam. 3:36)—a sense that is also attested in our context of the creation story, especially in God’s recognition: “It is not good that man should be alone.”[7] This divine statement clearly implies a relational dimension, including ethics, aesthetics, and even love and emotional happiness, as the immediate context suggests (Gen. 2:23; cf. Ps. 133:1). This divine evaluation is particularly significant as it appears to be in direct connection to the first creation story, which was deemed good.

In the second creation story (Gen. 2:4b–25), the word ṭôb occurs five times, thus playing the role of a keyword in response to the seven occurrences of ṭôb of the first creation story (1:1–2:4a). This echo between the two creation stories by means of the word ṭôb sheds light on the meaning of that word. While lōʾ ṭôb, “not good,” alludes negatively to the perfect and complete creation of the first creation story,[8] the phrase ṭôb wārāʿ, “good and bad”—the word and its contrary— suggests that the word ṭôb, “good,” should be understood as expressing a distinct and different notion from raʿ, “bad, evil.” The fact that creation was good means, then, that it contained no evil.[9]

The reappearance of the same phrase in Genesis 3:22 will confirm this argument from another perspective. The knowledge of good and evil, suggesting discernment or knowing the difference between right and wrong,[10] was only possible when “Adam was like one of us in regard to the distinguishing between good and evil.”[11] The verb hāyâ, “was,” is a perfect form and refers to a past situation.[12] It is only when Adam was like God, not having sinned yet from the perspective of pure good, that Adam was able to distinguish between good and evil. The same line of reasoning may be perceived, somewhat in a parallel way, in regard to the issue of death, which is in our context immediately related to the issue of the knowledge of good and evil. Indeed, the tree of life is associated with the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Gen. 2:9), as they are located at the same place “in the midst of the garden” (2:9; 3:3). And Adam is threatened with the loss of life as soon as he fails to distinguish between good and evil (2:17). For just as good (without evil) is the only way to be saved from evil, life (without death) is the only antidote to death.

It is also noteworthy that this divine appreciation of good does not concern God. Unlike the Egyptian stories of creation, which emphasize that a god created only for his own good, for his own pleasure, and that his progeny was only accidental,[13] the Bible insists that the work of creation was deliberately intended for the benefit of God’s creation and essentially designed for the good of humans (Ps. 8). Indeed, the two parallel texts of creation in Genesis 1 and 2 teach[14] that perfect peace reigned initially. In both texts, humankind’s relationship to nature is described in the positive terms of ruling and responsibility. In Genesis 1:26, 28, the verb rādâ, “to have dominion,” which is used to express humankind’s relationship to animals, is a term that belongs to the language of the suzerain-vassal covenant[15] and of royal dominion[16] without any connotation of abuse or cruelty.[17] In the parallel text of Genesis 2, humankind’s relationship to nature is also described in the positive terms of covenant. Humankind gives names to the animals and, thereby, not only indicates the establishment of a covenant between humankind and them but also declares lordship over them.[18] That death and suffering are not part of this relationship is clearly suggested in Genesis 1 by the fact that this dominion is immediately associated with food which is designated to both humans and animals; it is just the product of plants (Gen. 1:28–30). In Genesis 2, the same harmony is conveyed by the fact that animals are designed to provide companionship for humans (v. 18).

At this point in the story, humankind’s relationship to God has not suffered any disturbance. The perfection of this relationship is suggested through a description of that relationship only in positive terms: Genesis 1 mentions that humankind has been created “in the image of God” (vv. 26, 27), and Genesis 2 reports that God was personally involved in creating humans and breathed into them the breath of life (v. 7). Likewise, the relationship between man and woman is blameless. The perfection of the conjugal unity is indicated by mentioning that humankind has been created in Genesis 1 as male and female (v. 27) and, in Genesis 2, through Adam’s statement about his wife being “bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh” (v. 23). The whole creation is described as perfect. Unlike the ancient Egyptian tradition of origins, which implies the presence of evil already at the stage of creation,[19] the Bible makes no room for evil in the original creation. Significantly, at the end of the work, the very idea of perfection is expressed through the word wayĕkal (Gen. 2:1, 2), qualifying the whole creation. This Hebrew word, which is generally translated “finished” (NKJV) or “completed” (NIV), conveys more than the mere chronological idea of “end”; it also implies the quantitative idea that nothing is missing, and there is nothing to add, again confirming that death and all evil were totally absent from the picture.

Furthermore, the biblical text does not allow for the speculation of a pre-creation involving death and destruction. The echoes between introduction and conclusion indicate that the creation referred to in the conclusion is the same as the one mentioned in the introduction.

The “heavens and earth,” which are mentioned in Genesis 2:4a, at the conclusion of the creation story,[20] are the same as in Genesis 1:1, the introduction of the creation story. The echoes between the two framing phrases are significant.[21]

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. (Gen. 1:1)

This is the history of the heavens and earth when they were created. (2:4)

The fact that the same verb bārāʾ, “created,” is used to designate the act of creation and with the same object (“heavens and earth”) suggests that the conclusion points to the same act of creation as the introduction. In fact, this phenomenon of echoes goes even beyond these two lines. Genesis 2:1–3 echoes Genesis 1:1 by using the same phrase but in reverse order: “created,” “God,” and “heavens and earth” of Genesis 1:1 reappear in Genesis 2:1–3 as “heavens and earth” (v. 1), “God” (v. 2), “created” (v. 3). This chiastic structure and the inclusion “God created,” linking Genesis 1:1 and Genesis 2:3, reinforce the close connection between the two sections in the beginning and the end of the text, again confirming that the creation referred to at the end of the story is the same as the creation referred to in the beginning of the story. The event of creation found in Genesis 1:1, 2:4a is then told as a complete event, which does not complement a prework in a far past (gap theory) nor is it to be complemented in a postwork of the future (evolution).[22]

THE “NOT YET” OF CREATION

It seems, in fact, that the whole Eden story has been written from the perspective of a writer who already knows the effects of death and suffering and, therefore, describes these events of Genesis 2 as a “not yet” situation. Significantly, the word ṭerem, “not yet,” is stated twice in the introduction of the text (Gen. 2:5) to set the tone for the whole passage. And further in the text, the idea of “not yet” is indeed implicitly indicated. The ʿāfār, “dust,” from which humankind has been formed (2:7) anticipates the sentence of chapter 3: “To dust you shall return” (v. 19). The tree of the knowledge of good and evil (2:17) anticipates the dilemma of humankind later confronted with the choice between good and evil (3:2–6). The assignment given to humankind was to šāmar, “keep,” the garden in its original state,[23] which implies the risk of losing it, therefore anticipating God’s decision in Genesis 3 to chase them out of the garden (v. 23) and to entrust the keeping (šāmar) of the garden to the cherubim (v. 24). This same word šāmar is used in both passages showing the bridge between them—the former pointing to the latter suggesting the “not yet” situation. Likewise, the motif of shame in Genesis 2:25 points to the shame they will experience later (3:7).[24] The same idea is intended through the play on words between ʿārôm, “naked,” and ʿārûm, “cunning,” of the serpent; the former (2:25) is also a prolepsis[25] and points forward to the latter (3:1) to indicate that the tragedy, which will be initiated through the association between the serpent and human beings, has not yet occurred.[26] Indeed, as Walsh notes, “There is a frequent occurrence of prolepsis in the Eden account.”[27]

DEATH WAS NOT PLANNED: THE REVERSAL OF CREATION

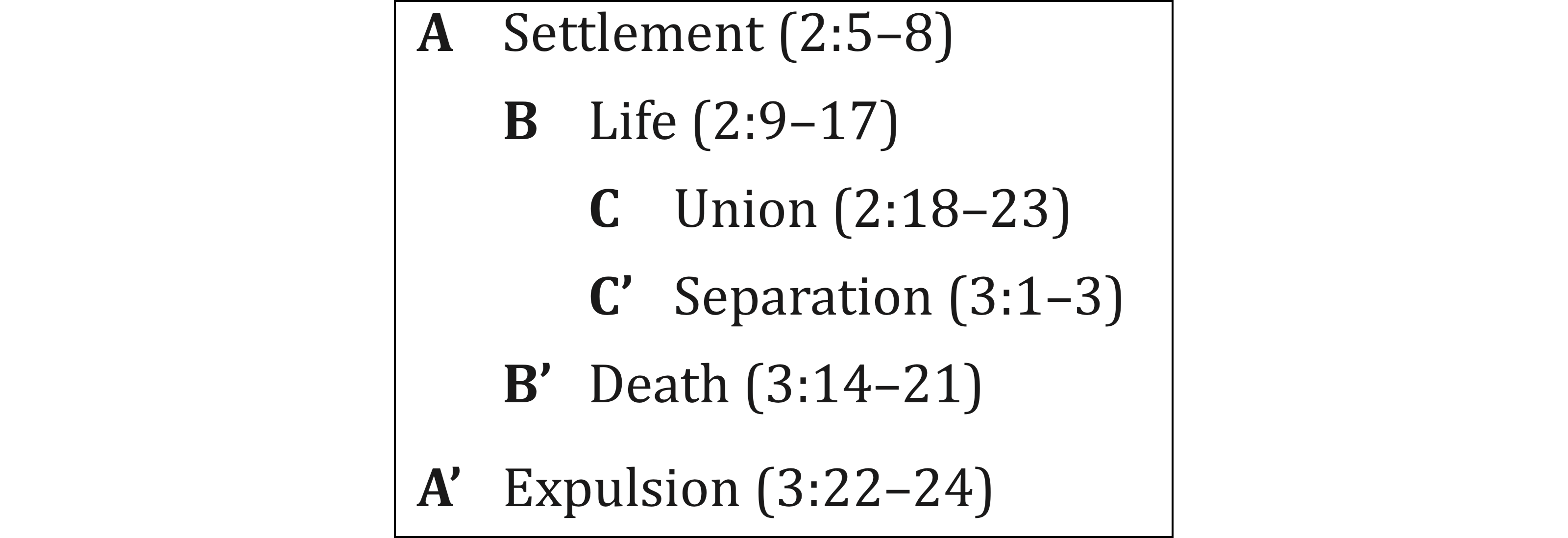

The biblical text goes on in Genesis 3 to tell us that an unplanned event happened and reversed the original picture of peace into a picture of conflict:[28] conflict between animals and humans (Gen. 3:1, 13, 15); between man and woman (Gen. 3:12, 16, 17); between nature and humans (Gen. 3:18, 19); and finally, with humans against God (Gen. 3:8–10, 22–24). Death makes its first appearance since an animal was killed in order to cover humankind’s nakedness (Gen. 3:21), and death is now clearly profiled on the horizon of humankind (Gen. 3:19, 24). The blessing of Genesis 1 and 2 has been replaced with a curse (Gen. 3:14, 17). Indeed, the original ecological balance has been upset and only the new incident of the sin of humankind is to be blamed for this. This theological observation is also reflected in the literary connection between the biblical texts. It is indeed significant that Genesis 3 is not only telling the events that reversed creation; the story of Genesis 3 is also written in the reversed order of the story of Genesis 2, following the movement of the chiastic structure (ABC//C’B’A’):[29]

The correspondence between the sections is also supported by the use of common Hebrew words and expressions.[30] This literary reversal of motifs—settlement-expulsion, life-death, union-separation— confirms the intention of the biblical author, namely, that sin provoked the reversal of the original creation.

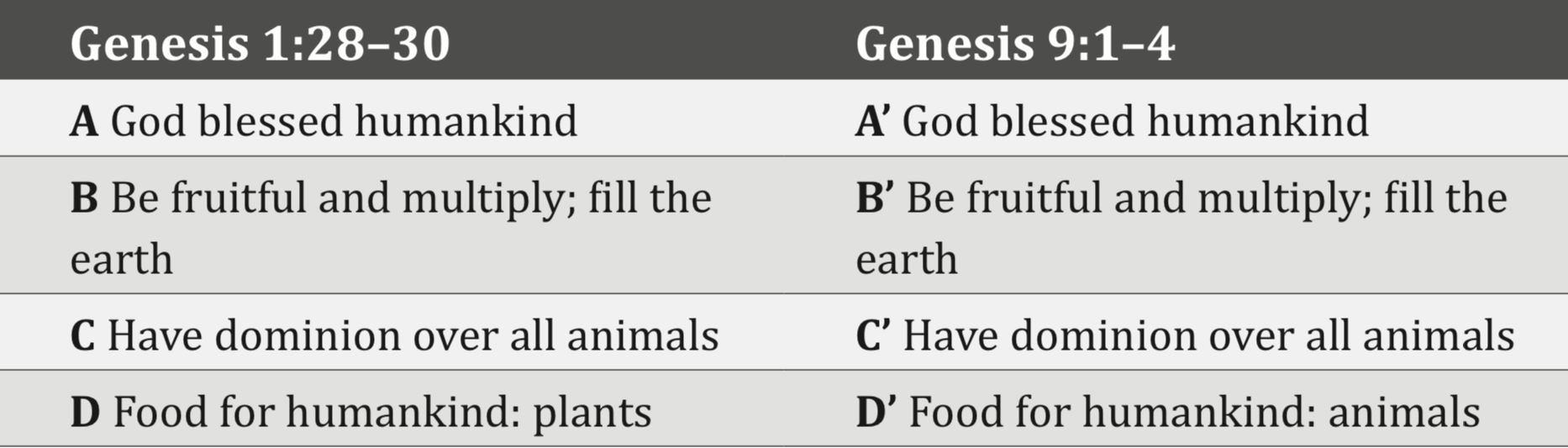

Later, this is the same principle that is behind the eruption of the Flood, since the cosmic disruption is directly related to the iniquity of humankind (Gen. 6:13). As Clines notes, “The flood is only the final stage in a process of cosmic disintegration which began in Eden.”[31] More particularly, the picture of the harmonious relationship between humankind and animals depicted in Genesis 1 is again disrupted after the Flood (Gen. 9:1–7). The literary bridge between the two passages[32] indicates that the relationship was upset after the creation and is not a natural part of it. Among a number of common motifs, the same concern with the relationship between humankind and animals can be found. The parallelism is striking:

The parallelism works not only in the fact that both passages use the same words and motifs but also in the fact that these occur in the same sequence. No doubt, the connection between the two passages is intended. One important difference, however, concerns the relationship between humankind and animals. Although it is packed with the same ingredients—humankind, animals (beast, birds, and fish), and food given by God—the nature of this relationship has changed. While in Genesis 1 humankind’s relationship to animals is peaceful and respectful (see earlier regarding vv. 29, 30), in Genesis 9, it is made of fear and dread on the part of every beast, which is “given into your hand” (v. 2).[33] The reason for this change is suggested in the texts. Since the peaceful relationship in Genesis 1 is associated with the herbal food for humankind, and the conflict relationship in Genesis 9 is associated with the animal food, the conclusion may be drawn that it is the dietary change, the killing of animals, that has affected the humankind-beast relationship.

In other words, the picture of conflict is not understood to be original and natural but as a result of an ecological unbalance, which is due essentially to death—the fact that humans (as well as animals) started hunting. It is noteworthy that the consumption of herbal food was a part of creation, as death was not yet implied at that stage; this is confirmed by the second Genesis creation story, which specifies that the eating of fruit preceded and, therefore, excluded the appearance of death (Gen. 2:16, 17).

THE BIBLICAL VIEW OF DEATH

It is significant that the overwhelming majority of occurrences of the technical word for death, mût, refers to human beings, rarely applies to animals (Gen. 33:13; Exod. 7:18, 21; 8:9 [13]; 9:6 f.; Lev. 11:39; Eccles. 3:19; Isa. 66:24), and is never used for plants per se.[34] The same perspective is reflected in the use of the word nepeš, “life,”[35] whose departure is the equivalent of death,[36] which also applies generally to humans, sometimes to animals, but never to plants. The reason for this emphasis on human death (versus animals and plants) lies in the biblical concern for human salvation and the place of human consciousness and human responsibility in the cosmic destiny.[37] Death is related to human sin, as noted in Romans 6:23, and sin belongs essentially to the human sphere (Gen. 2:17; Num. 27:3; Deut. 24:16; Ezek. 3:18; Jer. 31:30). It is significant that the first and the last appearances of death in the history of humankind are, in the Bible, associated with human sin and human destiny (Gen. 2:17; Isa. 25:8; Rev. 21:3, 4). The old lesson that “no man is an island” is invariably registered in the pages of the Bible,[38] with all the responsibility and the tragic destiny this organic connection implies for humankind. Thus, the biblical view of death is essentially different from the one proposed by evolution. While the belief in evolution implies that death is inextricably intertwined with life and, therefore, has to be accepted and eventually managed, the biblical teaching of creation implies that death is an absurdity to be feared and rejected. Evolution teaches an intellectual submission to death.

The Hebrew view of death was unique in the ancient Near East. While the Canaanites and the ancient Egyptians normalized or denied death through the myths of the gods of death (Mot and Osiris), the Bible confronts death and utters an existential shout of revolt and a sigh of yearning (Job 10:18–22; 31:35–36; Rom. 8:22). For the biblical authors, death is a contradiction to the Creator-God, Who is pure life. The expression “God [the Lord] is alive [ḥay]” is one of the most frequently used phrases about God.[39] Holiness, which is the fullness of life, is incompatible with death. In the Mosaic law, the blood was forbidden to be consumed, precisely because the “life of the flesh is in the blood” (Lev. 17:11; see also Gen. 9:4); corpses were considered unclean; and any person who had been in contact with death would become unclean for seven days and, for that period of time, would be cut off from the sanctuary and the people of Israel (Num. 19:11–13). Priests who were consecrated to God were even forbidden to go near a dead person; they were prohibited from entering a graveyard or attending a funeral, unless it was for a close relative (Num. 21:1, 2; Ezek. 44:25). All these commandments and rituals were meant to affirm life and to signify the Hebrew attitude toward death “as an intruder and the result of sin.”[40]

WHEN DEATH SHALL BE NO MORE: AN ARGUMENT FROM THE FUTURE

It should not come as a surprise, then, that the biblical prophets understood hope and salvation as a total re-creation of a new order where humankind and nature will enjoy God’s last reversal, where creation will be totally good again and no longer affected by sin and where death will be no more (Isa. 65:17; 66:22; Rev. 21:1–4). In this new order, good will no longer be mixed with evil, as death will no longer be mixed with life. It will be an order where the glory of God occupies the whole space (Rev. 21:23; 22:5). As Irving Greenberg points out, “In the end, therefore, death must be overcome. ‘God will destroy death forever. My Lord God will wipe the tears away from every face.’ (Isaiah 25:8). . . . In fact, since God is all good and all life, ideally there should have been no death in God’s creation in the first place.”[41] The hope for the new creation of heavens and earth where death shall be no more provides us, from the future, with an additional confirmation that death was not a part of God’s original creation.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The biblical story of origins teaches that death was not a part of the original creation for four fundamental reasons, provided by the biblical testimony of creation:

- Death was not a part of creation, because the story qualifies creation as good, that is, without any evil.

- Death was “not yet,” because the story is characterized as a “not yet” situation, from the perspective of someone whose condition is already affected by death and evil.

- Death was due to human sin, which resulted in a reversal of God’s original intention for creation.

- That death was not intended to be a part of God’s original creation is evidenced in the future re-creation of the heavens and earth, where death will be absent.

The close literary reading of the Genesis texts suggests that there is even a deliberate intention to emphasize these reasons to justify the absence of death at creation:

- In the first creation story (Gen. 1:1–2:4a), the sevenfold repetition of the word ṭôb, “good,” reaching its seventh sequence in ṭôb mĕʾōd, “very good.”

- In the second creation story (Gen. 2:4b–25), the twofold repetition of the word ṭerem, “not yet,” and the prolepsis anticipating the “not yet” of Genesis 3.

- In the story of the Fall (Gen. 3), the literary reversal expressing the cosmic reversal of creation.

The tendency of the scientific community to assume that death was part of the original creation is understandable. On the basis of present observations, it is indeed impossible to conceive of life without death, just as it would be philosophically impossible to conceive of good without evil. Only the imagination of faith that takes us supernaturally beyond this reality allows us to transcend and even negate our condition. Only the visceral intuition of eternity, the life granted by God to all of us—“He has put eternity in their hearts” (Eccles. 3:11)—and the imagination of faith help us see beyond the reality of our present condition to realize that death has indeed nothing to do with life.

REFERENCES

[1] See S. R. Driver, The Book of Genesis, With Introduction and Notes (London: Methuen & Co., 1904), 3; see Claus Westermann, Genesis 1–11: A Commentary, trans. John. J. Scullio (Minneapolis, Minn.: Augsburg, 1984), 99; and more recently, Ellen J. van Wolde, Reframing Biblical Studies: When Language and Text Meet Culture, Cognition, and Context (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2009), 184–200.

[2] Ludwig Koehler and Walter Baumgartner, ed., Lexicon in Veteris Testament Libros, 2nd ed. (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1958), 147.

[3] See Jan Bergman, “ברא, bārāʾ,” in TDOT, vol. 2, 242–44.

[4] Ibid., 245, 46.

[5] For the notion of “totality” in Hebrew thought, see especially Johannes Pedersen,

Israel: Its Life and Culture (London: Oxford University Press, 1964), 108; see Jacques B. Doukhan, Hebrew for Theologians: A Textbook for the Study of Biblical Hebrew in Relation to Hebrew Thinking (New York: University Press of America, 1993), 195.

[6] See John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate (Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP Academic, 2009), 51, 149–51.

[7] Scripture quotations in this chapter are taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

[8] See James McKeown, Genesis, THOTC (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2008), 33.

[9] The reference to raʿ, “evil,” next to ṭôb, “good,” and the presence of the serpent, the manifestation of evil in Genesis 3, do not mean that evil was a part of God’s creation. Evil was there, but it had not yet affected the divine creation of the human world and, hence, human nature. As long as humans had not received it in their hearts, evil remained just an external threat (see below for my comments on Gen. 3:22; compare also John 14:30 for Jesus’s case).

[10] See 2 Samuel 14:17; cf. 1 Kings 3:9.

[11] My literal translation, cf. Young’s literal translation: “And Jehovah God said ‘Lo, the man was as one of us as to the knowledge of good and evil.’”

[12] The same form is used in Genesis 3:1 to describe that “the serpent was [hāyâ] more cunning.” If the idea of “becoming” was intended (the usual translation), the Hebrew should have used the preposition lĕ (“to”) following the verb hāyâ (“to be”); see, for instance, in Genesis 2:10: “became (hāyâ lĕ) four riverheads.” See Jacques B. Doukhan, All Is Vanity: Ecclesiastes (Nampa, Id.: Pacific Press, 2006), 74.

[13] See James Allen, Genesis in Egypt: The Philosophy of Ancient Egyptian Creation Accounts, YES, 2 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988), 43, 44.

[14] On the parallelism between the two Genesis creation stories in Genesis 1 and 2, see Jacques B. Doukhan, The Genesis Creation Story: Its Literary Structure, AUSDDS, 5 (Berrien Springs, Mich.: Andrews University Press, 1978), 73, 74.

[15] See 1 Kings 4:24; 5:4; Ps. 72:8; 110:2; Isa. 14:2.

[16] See Num. 24:19; 1 Kings 5:4 (4:24); Ps. 72:8; cf. H. J. Zobel, “ָר ָדה , rādâ,” in TDOT, vol. .333 ,13

[17] Note the fact that the Hebrew text needs to specify “with cruelty” (Lev. 25:43, 46, 53), since the verb rādâ generally indicates a neutral sense for this word.

[18] See Genesis 32:28; 41:45; Dan. 1:7; Num. 32:38; 2 Kings 23:34; 24:17; 2 Chron. 36:4; see Umberto Cassuto, A Commentary on the Book of Genesis (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1974); Claus Westermann, Creation (London: SPCK, 1974), 85.

[19] Indeed, the actual presence of isefet, “evil,” or antilife, in creation is implied in the presence of Seth, suggesting that the Egyptian account of creation already contains the seeds of its corruption. This involvement of an evil power may explain why the ancient cosmologies needed to resort to the fundamental theme of a conflict and battle between two opposed forces. In fact, Egyptian creation is made possible only by nonexistence. See Erik Horning, Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many, trans. John Baines (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1982), 165.

[20] As McKeown, Genesis, 29, notes, “It is difficult to decide whether this occurrence of the phrase is a conclusion to the creation account in 1:1–2:3 or whether it is an introduction to what follows,” and then, upon the observation that Genesis 2:4a mentions “heavens and earth,” he concludes that this phrase “would be less appropriate as an introduction to the next section, in which the heavens are not prominent.” For P. J. Wiseman, Clues to Creation in Genesis, ed. Donald J. Wiseman (London: Marshall, Morgan, and Scott, 1977), 34–45, this phrase is a colophon, which always concludes a section in Genesis. Many commentators, however, think that this phrase should be understood as an introduction to what follows, although, as noted by McKeown, Genesis, 29, “This seems satisfactory for the majority of its occurrences but not for the first.” Regarding other reasons of a literary nature as to why this phrase should be treated as a conclusion, see Doukhan, Genesis Creation Story, 249–62. Because of the ambiguity of this function, it is also possible that this phrase serves both as a conclusion to what precedes and as an introduction to what follows, thus marking the “transition in the narrative, carefully integrating the creation account and the narrative of the garden to follow.” Kenneth A. Mathews, Genesis 1:1–11:26, NAC, 1a (Nashville, Tenn.: Broadman & Holman, 1996), 190.

[21] For other examples of this literary device, see Pss. 146–150, Exod. 15, and Dan. 9, where the conclusion points back to the introduction. See Meir Weiss, The Bible From Within: The Method of Total Interpretation (Jerusalem: Magnes Press and Hebrew University, 1984), 271–97. See also Jacques B. Doukhan, Daniel: The Vision of the End, rev. ed. (Berrien Springs, Mich.: Andrews University Press, 1989), 95–98.

[22] This completeness of the event of creation is also supported by the general structure of the introduction, which preludes God’s word, if we read it in a single breath, implying a construct state for the word bĕrēʾšît, “in the beginning of.” This reading, which relates the first word “in the beginning of” (Gen. 1:1) to “God said” (Gen. 1:3), excludes the idea of a pre-creation; see Doukhan, Genesis Creation Story, 53–73.

[23] The Hebrew word šāmar, “keep,” conveys the connotation of preserving in its original situation rather than the idea of protecting against; it is mostly used to express the idea of faithfulness to the law or to the covenant (Exod. 31:16; Deut. 7:9; 1 Sam. 13:13, 14; 1 Kings 8:23; 2 Kings 8:58, 61; 2 Chron. 22:12) and as a synonym to the word zākar, “remember,” as in Deut. 5:12, Exod. 20:8, Ps. 103:18, and Ps. 119:55, which then implies faithfulness to the past original state.

[24] B. N. Wambacq, “Or tous deux étaient nus, l’homme et la femme, mais ils n’en avaient pas honte (Gen 2:25),” in Mélanges bibliques en hommage au R.P. Beda Rigaux, ed. A. Descamps and A. de Halleux (Gembloux, Belgium: Deculot, 1970), 553–56.

[25] Jerome T. Walsh, “Genesis 2:4b–3:24: A Synchronic Approach,” JBL 92 (1977): 164. See Doukhan, Genesis Creation Story, 76.

[26] See Walsh, “Genesis 2:4b–3:24,” 161–77. See also Luis Alonso-Schökel, “Sapiential and Covenant Themes in Gen 2–3,” TD 13 (1965): 3–10; Doukhan, Genesis Creation Story, 76; Yosef Roth, “The Intentional Double-Meaning Talk in Biblical Prose” (Heb), Tarbiz 41 (1972): 245–54; Jack M. Sasson, “wĕlōʾ yitbōšāšû (Genesis 2, 25) and Its Implications,” Bib 66 (1985): 418.

[27] Walsh, “Genesis 2:46–3:24,” 164n12.

[28] See McKeown, Genesis, 37.

[29] I am indebted here (with slight modifications) to Zdravko Stefanovic, “The Great Reversal: Thematic Links between Genesis 2 and 3,” AUSS 32 (1994): 47–56.

[30] Ibid., 54, 55.

[31] David J. A. Clines, The Theme of the Pentateuch (Sheffield, England: JSOT Press, 1978), 75. Clines continues on the same page: “While ch. 1 views reality as an ordered pattern . . . , chs. 2–3 see reality as a network of elemental unions that become disintegrated throughout the course of the narrative from Eden to the Flood.”

[32] The re-creation of Genesis 8:9–17 is developed in parallel to the creation story of Genesis 1 in seven steps, and the current passage under discussion belongs to the sixth section (Gen. 8:18–9:7) corresponding to the sixth day (Gen. 1:24–2:1). For the connection between creation and the Flood, see Ps. 74:12–17 and 2 Pet. 3:5–13. See also Warren A. Gage, The Gospel of Genesis: Studies in Protology and Eschatology (Winona Lakes, Ind.: Carpenter Books, 1984), 16–20; see Doukhan, Daniel, 133, 34. In fact, the purpose of these literary, linguistic, and thematic correspondences between the two stories is not only to suggest that the same process of creation is at work in the Flood narrative but also that the judgment implied in the Flood brings about the reversal of creation, back to pre-creation: the same phrase ʿal-pĕnê hammāyim, “on the face of the waters,” which characterized that stage, is used again (Gen. 1:2; cf. 7:18); the waters once separated are now reunited, the dry land disappears, and the darkness and the tĕhôm, “the deep,” reappears (Gen. 8:2). Later, the prophets will also refer to this theme of creation’s reversal to evoke the judgment of God (cf. Isa. 24:18; Jer. 4:23–26; Amos 7:40).

[33] The expression “given into one’s hands” implies threat and aggression. See Job 1:12; 2:6; Josh. 8:7; 1 Chron. 14:10; 2 Chron. 28:9.

[34] The only reference to plants is, in fact, a metaphor to evoke the death of humans (see Job 14:1, 2, 10, 11).

[35] This meaning of “life” for nepeš is derived from the concrete original meaning of “throat” and, hence, of “breath”; see Claus Westermann, “nepeš, ‘soul,’” in TLOT, vol. 2, 759; see also the Akkadian napishtu, which denotes “the opposite of death.” See Wolfgang von Soden, “Die Wörter für Leben und Tod im Akkadischen und Semitischen,” BIFAO 19 (1982): 4.

[36] See J. Illman, “mût, מוּת,” in TDOT, vol. 8, 191.

[37] See Blaise Pascal, Pensées, 347: “Man is but a reed, the most feeble thing in nature; but he is a thinking reed. . . . But, if the universe were to crush him, man would still be more noble than that which killed him, because he knows that he dies and the advantage which the universe has over him; the universe knows nothing of this.”

[38] In Genesis 4, as a result of murdering his brother, Cain had to be protected. The text does not state from what, but it is clear that animals are implied since these are the only beings left besides his parents. The same principle underlies the Hebrew concept of the Promised Land, which has the property of “vomiting out” its sinful inhabitants (Lev. 18:25, 28). The iniquity of the Israelites—who kill, steal, and commit adultery (Hos. 4:2)—influences the character of the land, which “will mourn; and everyone who dwells there will waste away with the beasts . . . the birds . . . the fish” (Hos. 4:3). Likewise, the lie of the individual Achan bears upon the immediate surroundings. Not only will the whole people be hurt, but the space in which the sin takes place, the valley, is affected and becomes the “valley of trouble” (Josh. 7:10–26). Thus, the geography bears witness to the iniquity. This principle is so vivid in the Hebrew prophets’ minds that they go so far as to deduce the fate of the nation merely from the meaning of the names of the cities where they live (Mic. 1:10–16).

[39] See Josh. 3:10; Judg. 8:19; 1 Sam. 14:39; 25:34; Ps. 84:2; Ezek. 5:11.

[40] Elmer Smick, “mût, מוּת,” in TWOT, vol. 1, 497.

[41] Irving Greenberg, The Jewish Way: Living for the Holidays (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 183.