©Copyright 2018 GEOSCIENCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE

11060 Campus Street • Loma Linda, California 92350 • 909-558-4548

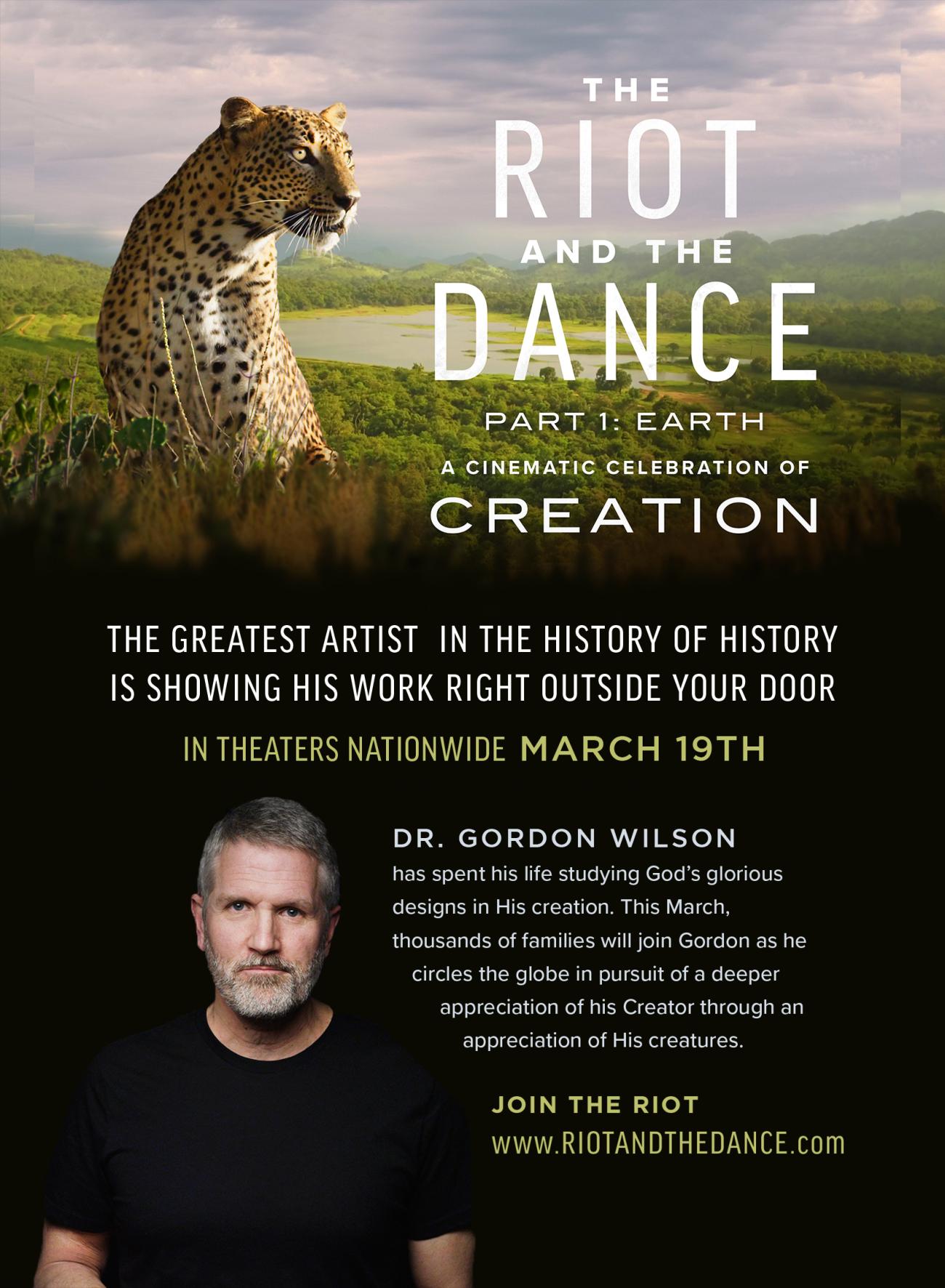

This movie premiered in US movie theaters on March 19, 2018, followed by a nationwide theatrical encore on April 19th. It is available on DVD format and for streaming on Amazon. More information and additional resources about the documentary can be found at http://riotandthedance.com and https://www.facebook.com/riotandthedance/

Most nature documentaries include some language that refers to an underlying naturalistic understanding of origins. They convey the idea that the deeply textured behaviors and interactions of the biological world emerged from impersonal physical necessities and a really long chain of purposeless chance events. However, the recently released nature documentary “The Riot and the Dance” breaks this common pattern in a refreshing way. Instead of suppressing the undeniable richness of meaning in nature, this film embraces with beautiful consistency a simple premise from its very start: God is the Maker of all there is and we resonate with other living beings because we all are the expression of His design and creativity. This bold choice sets this movie apart from classic nature documentaries and provides the foundation for the exploration of different habitats and their inhabitants. In speaking of other creatures, biologist Gordon Wilson, the narrating voice of the film, invites us to “see them truly as gifts, as miracles.” With reference to the redwood forests of the Pacific NW of the US, he remarks: “God has been using starlight to craft wooden towers older than the modern world. If He spared 2,000 years to shape something, can we spare the time to give it a glance?” In a moment of rare lyrical intensity, Wilson comments on a close up shot of a wild puma saying: “Look a puma in the face: really look. Know that its symmetry and grace was invented from nothing. Who can do such a thing? Only your Father.” What a joy to hear this kind of language punctuating quality videography of different aspects of the creation.

Openly embracing a theistic explanation for the origin of our world and the life that thrives in it has three direct consequences, clearly demonstrated in the movie: 1) First, it encourages wonder in the observer, because living creatures are received as works of art rather than machinery assembled by evolutionary engineering. This way of doing biology is not scared of poetry, and seeks to transcend the mere observation of the constitutive components of reality to spring into an act of celebration; 2) Second, it establishes a strong sense of responsibility founded on the traditional Christian understanding of creation, where humans are called to be keepers of this world. In Wilson’s words, “God has given us dominion and we have to take that charge very seriously.” The movie models an excellent example of how this responsibility requires mindful participation and continuous interrogation and can be fulfilled with playfulness and innocence rather than greed or disinterest; 3) Thirdly, it forces us to acknowledge the existence of tension and dissonance in the natural order when compared to the divine ideal revealed in the Scriptures. Nature is not only the source of thrilling wonder but also of perplexing realities not easily accounted for. This ambiguity is exactly what the title of the film, “The Riot and the Dance,” intends to convey. Something in the creation is not as it should be and we are puzzled by it, although we cannot mistake its evil nature.

The narrative trajectory of the movie starts with a brief opening section where Wilson introduces himself, and continues with a journey of exploration of different habitats and animals, covering local (US) and exotic (Sri Lanka) examples. A concluding section focuses on snakes, a common icon of natural evil, and after the closing credits there is an extensive appendix of interviews with Wilson and the film director (Wilson’s nephew), Ken Ham of Answers in Genesis, author Eric Metaxas, and Christian hip hop artist Propaganda. The major themes addressed throughout the movie are exploration and enjoyment of nature, environmental stewardship, and natural evil. I really liked that the nature sequences in the film are interjected by brief segments where Wilson speaks directly to the camera to introduce the discussion of those themes. However, some of the transitions between different habitats felt a bit disconnected, not always contributing to the construction of a compelling overarching story. The quality of the images and the spectrum of animal behaviors portrayed was very good. For me, some of the most impressive shots were close-ups of the scales of several reptiles caught by Wilson, showing beautiful coloration patterns. The high resolution shots zooming in on the geometric arrangement of the scales covering the skin of these animals certainly made me think of them as incredible living masterpieces. The closing interviews segment of the documentary helped to understand some of the history behind the making of the film, but was very different in style and made the movie perhaps too long. This did not leave the same flavor in our palate that had been constructed in the beautiful movie proper.

When it comes to the deeper reflections elicited by the film, I can think of two aspects that I would like to discuss more with Wilson to understand further his wisdom and perspective. The first is the possibility that heightened appreciation for the creation could translate into a sort of “nature worship.” If evolution has no place for intelligent design in nature, at the opposite side of the spectrum is a world where every minute detail is assigned incomparable value. Could this result in a posture towards the creation that is almost afraid of interaction and engagement for fear of disrupting a divinely ordained balance? To be fair, Wilson does not fall into this trap and projects a well-centered understanding of human rulership that is gentle and passionate, but not at all passive.

Director Andy Wilson explains in the final interview how he wanted to avoid the approach of other documentaries that “treat the animals as if they are sacred: the animals must not be touched, the animals take precedence over mankind.” However, in a scene where Wilson is crossing a river, we see him let a land leech crawl up his leg and draw a good sip of blood while he comments “Behold, God and I provide.” At times, I wonder if rather than turning back to God for all we observe in this world we should be impressed by how bad things have gone and read among the lines of nature the story of a cosmic conflict, elements of which we need to call out for what they are: not good. And again, Wilson seems to capture this tension by oscillating between the poles of wonder and appreciation but also statements affirming that “this is not how the world was meant to be, this is the result of the fall. It is more riot than it is dance.” However, he also appears to embrace the world as it is: “How much of this world does God love? How much has He given to us? The answer is the same: all of it. Every prickle and every pebble, every storm and every breeze, every insect and every lizard.” There is something tragic in the scene where a crested serpent eagle engages in an extenuating fight to kill a land monitor, but geckos preying on termites are apparently ok: God “makes them desperately want what He has already arranged to give them. Feast little lizards.” Maybe this tension is indeed where we should situate ourselves as Christian scientists in reading the message of the world around us.

The second aspect, connected to the first, is the stated desire to bring into the fold of this movie the narration of “Christian evolutionists.” Director Andy Wilson offers that “all of us should be able to look at the world and love what God gave us. Part of the goal of the film was not to have a debate movie where Christians fought with each other, but a film to celebrate what we all agree God gave us and then have some intermural debate about how He gave that to us.” But are animal death and predation part of “what we all agree God gave us?” If God uses natural selection to play His music, one would look at the hardships of animal life in a reverent rather than contrite and troubled way. But Wilson does promote throughout the movie the concept of the fall and the curse, and not only a spiritual one, but one that materially affected the biological world. He goes as far as to explicitly connect all the biological suffering to the results of our human choice: “Predator-prey, parasite-host, all these things are the result of the fall. The creation needs redemption.” “When man fell, so did the world, now death is something that we all share.” “Everything here is groaning against death because of our fall.” Therefore, it would be interesting to see how he sees that this approach can square with the perspective of a “Christian evolutionist.”

I was very grateful for and resonated with the perspective adopted in this movie. It is encouraging to see that new quality documentaries are being produced that embrace a language and a worldview in which many of us breathe and move. This film also provides a great opportunity to invite a skeptic friend to engage with a different way of looking at nature, that is genuine, honest, and joyous. I am looking forward to the release of the next episode of “The Riot and the Dance,” which will feature aquatic creatures!

Ronny Nalin, PhD

Associate Scientist

Geoscience Research Institute